Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

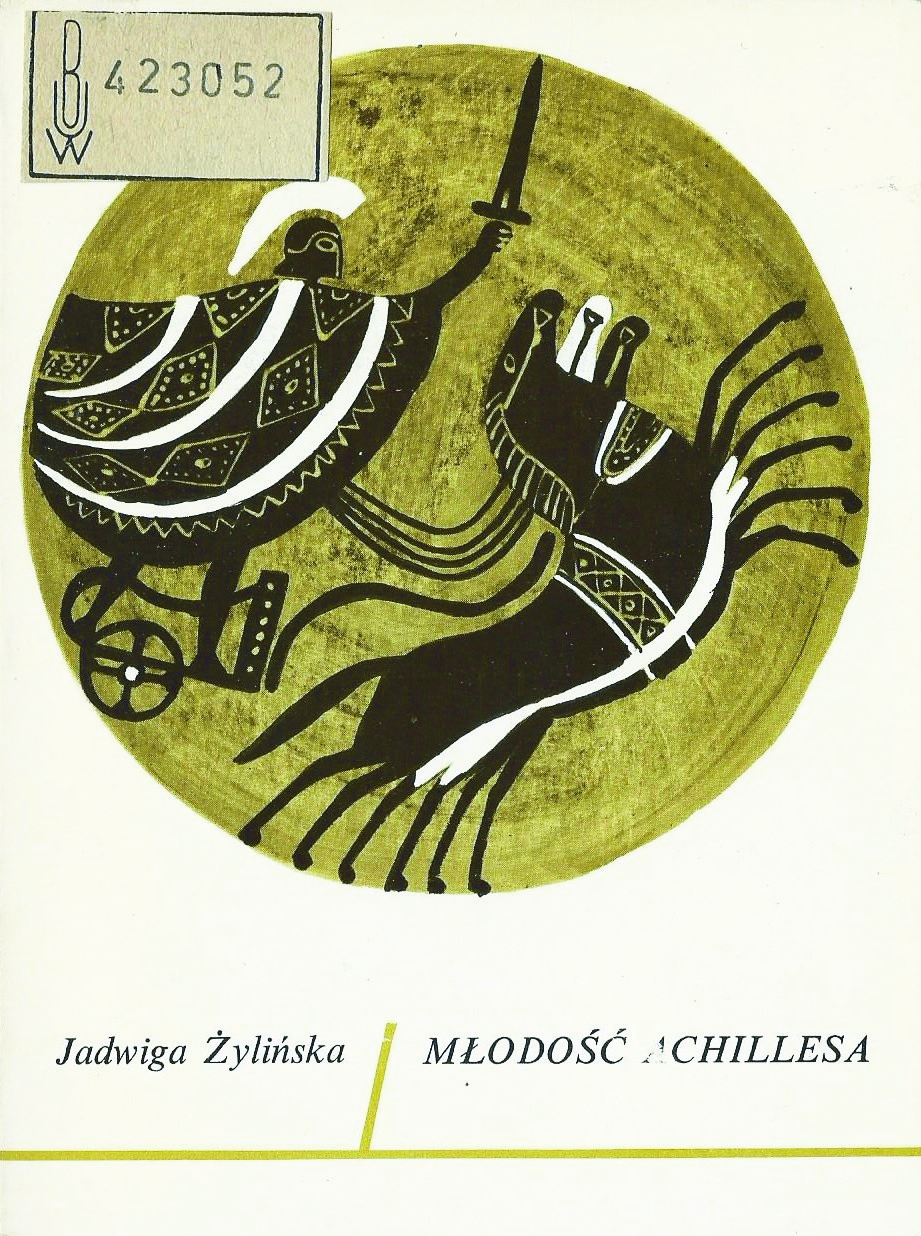

Jadwiga Żylińska, Młodość Achillesa. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch,” 1974, 60 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 1990 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Courtesy of Barbara Towpik-Roszkiewicz, daughter of the artist.

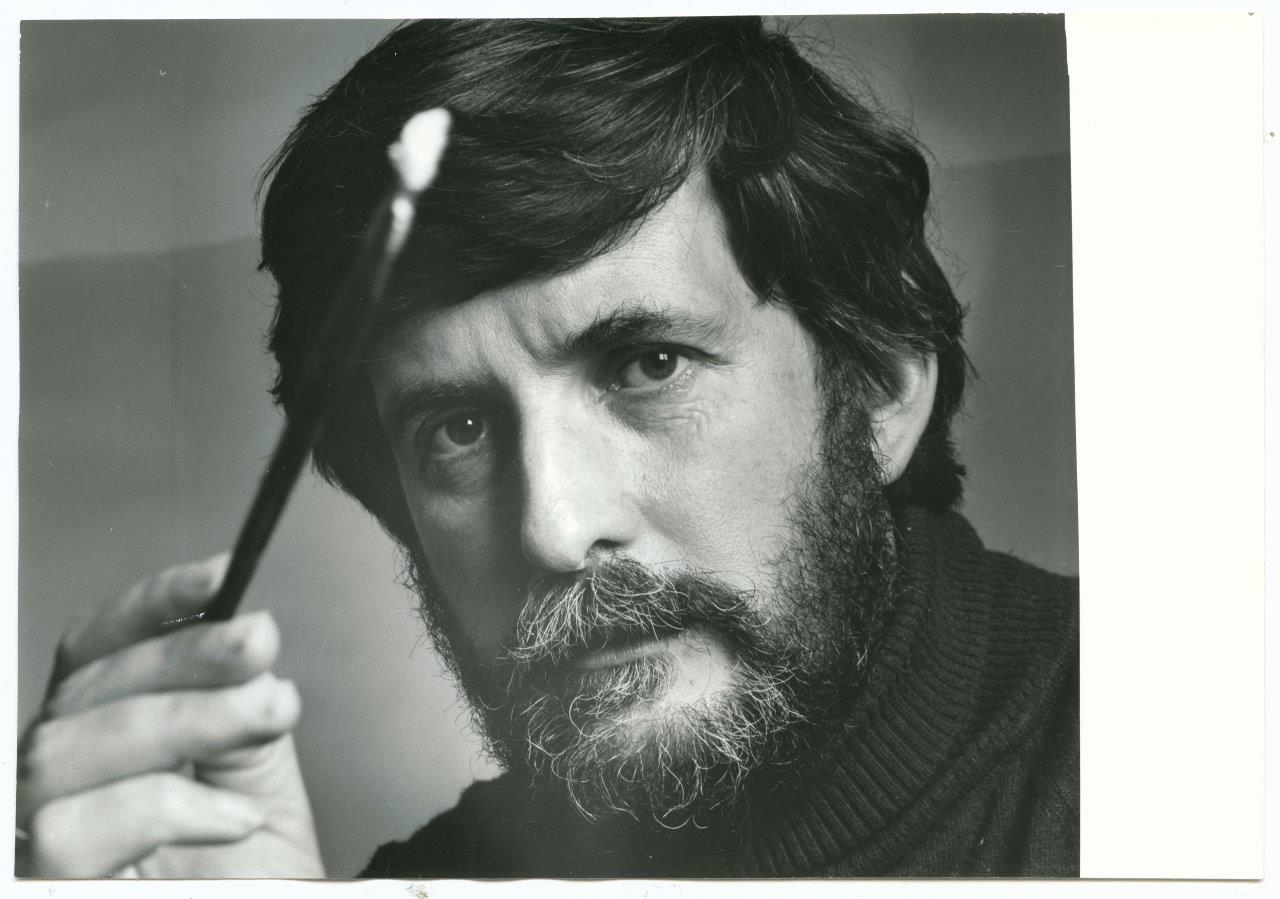

Janusz Towpik

, 1934 - 1981

(Illustrator)

Janusz Towpik (1934–1981), originally from Cieszyn, was an architect with a diploma from the Warsaw University of Technology [Politechnika Warszawska] (1959). He also studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw [Akademia Sztuk Pięknych] and became a graphic designer and an illustrator. He designed postcards, stamps, matchbox labels, ex libris, logotypes, tapestries and intarsias.

Towpik illustrated children’s books, textbooks, fairy tales, and other stories to be viewed with a projector, nature atlases, popular science books, especially those about animals, and produced zoological tables for the PWN Encyclopaedia. In addition, he taught drawing at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology and conducted an arts club for children at the Warsaw Zoo.

Selected publications illustrated by Janusz Towpik, examples of his works, awards and exhibitions can be viewed online here and here (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Sources:

janusztowpik.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik", at Artinfo.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik. Natura i Fantazja", at ownetic.com (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik – Czarodziej Natury", at muzeum.edu.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Gieżyński, Stanisław, Zwierzęta małe i duże, at Weranda.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Towpik-Roszkiewicz, Barbara, Janusz Towpik, at Legendy Polskiego Jeździectwa website (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph courtesy of its Author, Elżbieta Lempp.

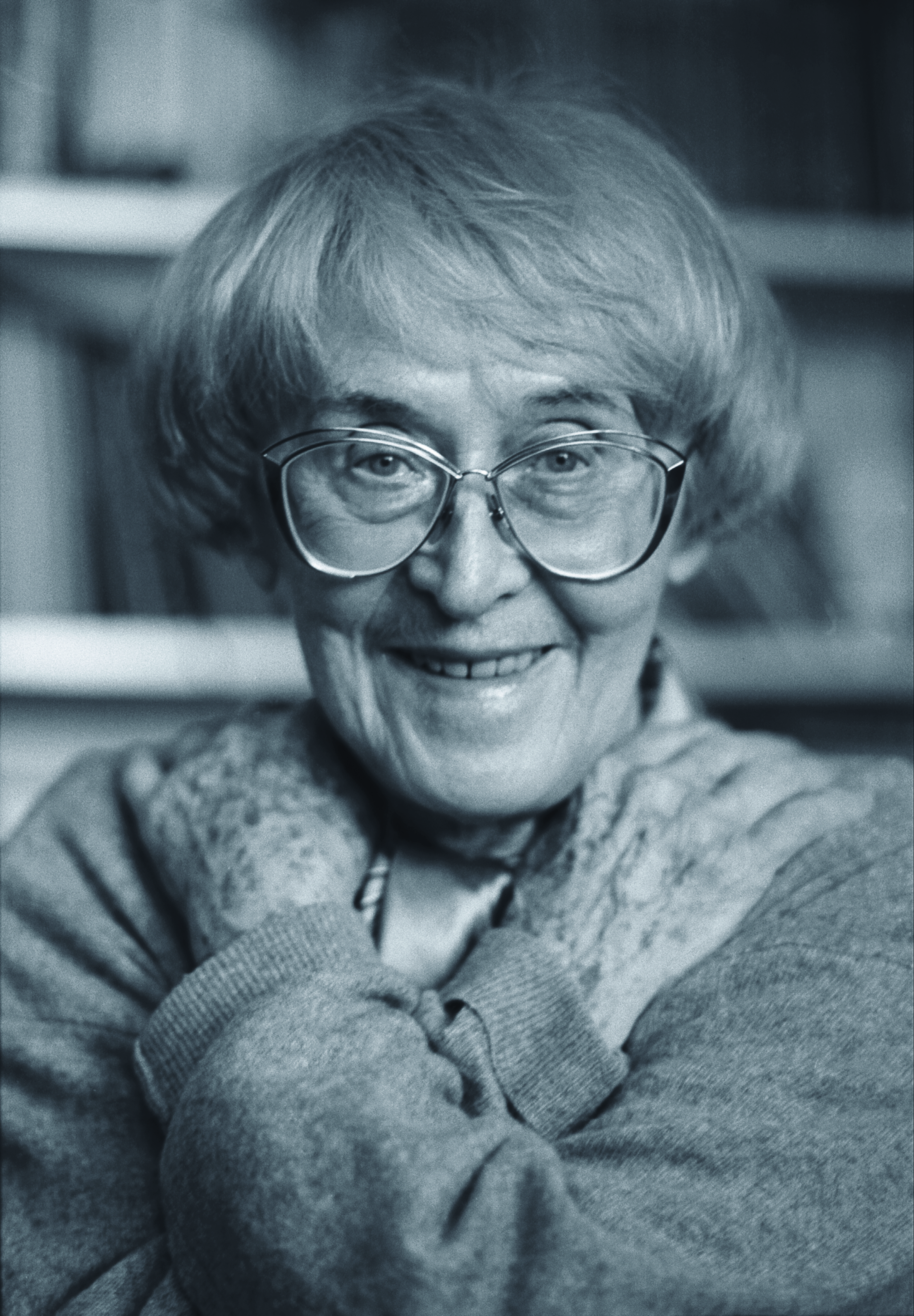

Jadwiga Żylińska

, 1910 - 2009

(Author)

Born in Wrocław, lived in southern Wielkopolska [Greater Poland] (Ostrzeszów and Ostrów Wielkopolski), which influenced her later life. Graduated in English philology from the University of Poznań. Proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and French. For many years worked for the Polish Radio. Prose writer, essayist, author of screenplays, radio dramas, historical novels, and books for children and young readers. Well known as an author of historical novels written from a woman’s point of view (the most important among these is a 2-volume novel Złota włócznia [The Golden Spear], 1961–1964). She made her debut in 1931 with a story for children Królewicz grajek [The Prince Piper] published in a periodical (still under her maiden name Michalska). Since 1964 member of the Polish PEN Club, in 1993 received the Polish PEN Club prize for lifetime achievement as a prose writer. Decorated with the Knight’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements for Polish culture. Some of her books were translated into German and Russian. She is the author of a cycle Oto minojska baśń Krety [Here is the Minoan Tale of Crete], 1986, parts of which were also published separately.

Source:

Żylińska Jadwiga, in: Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Wspołcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 10: Ż, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2007, pp. 66–69.

Bio prepared by Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The author presents Achilles’ life but not the well-known version told by Homer in the Iliad. The story begins with the nuptials of Achilles’ parents, the nymph Thetis (in this version of the myth, she is the daughter of Chiron, not of Nereus) and Peleus, king of the Myrmidons, a great but mortal warrior. Achilles, their son, is mortal as well. To make him immortal, Thetis pours ambrosia on Achilles’ body and holds him over a fire by his heel; unfortunately, Peleus interrupts the ritual and Achilles’ heel remains vulnerable. The narration proceeds with the hero’s early childhood: first with his grandfather Chiron, the famous Centaur teacher and then at the court of Lycomedes, king of the island Scyros where Achilles, disguised as a girl, is hidden by his mother among the daughters of the ruler. The following chapters are about Calchas’ prophecy and the arrival of envoys from Agamemnon, disguised as merchants, who come to Scyros to recruit Achilles. Next is Achilles’ participation in the Trojan War, illustrated with quotations from Homer’s Iliad (in the translation by Franciszek Ksawery Dmochowski in the late 18th century). The last chapter, entitled Apoteoza Achillesa [The Apotheosis of Achilles], centers on his posthumous fame.

Analysis

Młodość Achillesa retells the myths connected with the entire life of Achilles, preceded by events before his birth – the past of Peleus and the story of his wedding with Thetis. The author’s source is, of course, The Iliad, but she also uses Apollonius’ Argonautiká and Statius’ Achilleid containing less known versions and combines the ancient plots in her own way.

Achilles is presented as a child raised without a father from infancy. At first, he lives at his grandfather’s home, where he is educated in many ways to become a hero. The learning process is demanding, but the reader can also see Achilles in a family scene with Cheiron, Calliope and Thetis visiting him in happy moments of peace. Before the war, Scyros becomes his new home and king’s daughters – a second foster family. Surprisingly, Achilles finds good company and care – he and his new „sisters” spend time together in harmony; they take care of each other, learn from one another and tell stories. After a few years, Achilles announces his intention to marry the eldest, Deidamia, in the future. Unfortunately, the false merchants – Nestor, Ajax and Odysseus – discover his identity, and Achilles decides to take part in the war. The farewell to his bride-to-be shows that she hopes for his return, while he knows for sure that he sees her for the last time. His desire for immortal fame is much greater than his attachment to Deidamia. From this moment on, young Achilles is convinced of his greatness and importance. His father gives him the scepter of his ancestors, armour of the gods, stallions of Poseidon and Cheiron’s spear, so heavy that no one can throw it. To add to the importance of his house, Peleus also demands that Achilles lead the fleet and not sail under the command of Agamemnon, all before earning any merits. For such a young and inexperienced boy, it is an introduction to corruption. From the moment he killed Apollo’s son Tanes, Achilles grasps that he will die before even reaching the Trojan shore. His rage grows and remains with him during the whole war. In his rage, the young warrior conquers and pillages cities and even captures Pegasus and hitches him to his chariot. He feels rage when he is insulted by Agamemnon; his rage makes him reproach his mother with bitter and unjust words; he kills Hector in a rage and mistreats his dead body with abandonment. The author states that the Iliad is about Achilles’ courage, cruelty, loyalty and wrath (p. 53). She evaluates Achilles’ character negatively because his immortality and vivid presence in culture occur "not due to his wild courage and insane cruelty, but because of the taint of weakness which caused his death and is present in casual language as the expression Achilles’ heel" (p. 57). His name becomes immortal despite his superhuman hubris; rather than what is ordinary and common to all people in him (p. 57).

In Żylińska’s interpretation of the female protagonist, Thetis is as important as Achilles himself. In the world of men, she can be considered a strong and independent woman. The author presents her as a high priestess of the Moon goddess in Iolcus, one of three daughters of Cheiron, the king of the tribe of Centaurs. Thetis is, however, neither a centaur nor a human but rather a nymph. According to Cheiron, she is similar to his mother, Philyra the Oceanid, which explains her connection to water. As an immortal nymph, she can behave differently to ordinary women – she is free to marry whom she wants, and Peleus is not her choice, even if her father favours him and helps him convince Thetis. Finally, she agrees to marry Peleus not out of love or convenience but because of his abusive physical force: "he barred her way and seized her in his arms" (p. 7), "insisted and held her in a tight embrace" (p. 8). As a wife, Thetis did not bond strongly with her husband; when Peleus interrupts the process of making the infant Achilles immortal, Thetis abandons her spouse immediately, takes his only son and heir with her, and returns to her father. She informs Cheiron that she will never return to Peleus because she feels comfortable in the sea and not on land by his side. She stops being a wife but not a mother. Always with her son’s welfare in mind, she asks Cheiron to bring up Achilles and give him the best male education. She tries to protect the child from the prophecy of his possible death. Having heard that the war is coming, she goes to Lycomedes, asks him a favour and gives him her precious wedding gift made of gold by Hephaestus himself. When the young Achilles is finally sent to Peleus to prepare for war, she provides him with many practical gifts (a mantle, a warm blanket to protect from the cold, wind and rain), some precious advice, and promises to come every time he calls her. When Achilles feels insulted by Agamemnon’s offensive and unjust treatment, she embraces and consoles him (p. 50). After Patroclus’ death, the enraged Achilles reproaches his mother for her marriage with a mortal and, in consequence, his mortality (p. 51). She does not respond with anger but helps him though she knows that it would lead him to his death. As a loving immortal mother of her mortal son entangled in prophecies, Thetis seems to be the most tragic character as she is helpless against fate but tries to oppose it and save her child.

The third important character portrayed in the story is Cheiron. He is the king of the tribe of Centaurs and the son of an Oceanid. Centaurs are not explicitly described here as hybrid creatures. However, Żylińska uses the form centaury and not Centaurowie, and personal pronouns ("je" and not "ich") indicating they are animals rather than humans. Even if Cheiron says that "Centaurs and Nymphs are not exactly human" (p. 15), the reader can assume they are just a tribe like many others, but somehow special, especially that the ruler himself is described as an extraordinary person and an extraordinary preceptor. Cheiron’s wisdom and skill as a teacher has been proven when gods’ sons attended his “boarding school”, but in Achilles’ upbringing, his role is even more important as he is a relative in loco parentis.

Further Reading

Sucharski, Robert A., “Jadwiga Żylińska’s Fabulous Antiquity”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Boston–Leiden: Brill, 2016, 120–126.