Title of the work

Studio / Production Company

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Król Midas. Directed by Lucjan Dembiński, screenplay by Ryszard Budzyński, music by Krzysztof Penderecki, design by Adam Kilian. Se-Ma-For, 1963. 10 min.

Running time

Format

Available Onllne

Król Midas at Ninateka.pl (accessed: February 20, 2024).

Król Midas at vod.tvp.pl (accessed: April 23, 2021).

Król Midas version with commentary for disabled persons at adapter.pl (accessed: April 23, 2021).

Frames available at fototeka.fn.org.pl (accessed: July 21, 2022).

Genre

Animated films

Puppet films

Short films

Silent films

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Frames from the animation. Copyright protected. Courtesy of Filmoteka Narodowa.

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Lucjan Dembiński

, 1924 - 1998

(Director)

Lucjan Dembiński (1924–1998) graduated from the Faculty of Puppetry at the Theater Academy PWST in Cracow, an actor-puppeteer, screenwriter and director of animations. At the beginning of his career, he acted and directed at the “Rozmaitości” theatre in Wrocław. Since 1958 he was connected with Se-Ma-For studio. His best-known works were episodes in the French-Polish animated series Przygody Misia Colargola [The Adventures of Colargol the Bear], Przygody Misia Uszatka [The Adventures of Uszatek the Bear] and almost 30 episodes in the Moomins series. He directed almost a hundred animated films for children and was awarded many collective and individual prizes in Poland and abroad, for instance, at the Grand Prix of International Children and Young Adults Film Festival in Paris for The Adventures of Colargol the Bear in 1972.

Source:

Filmpolski.pl (accessed: May 21, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Retrieved from Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe (accessed: December 17, 2021).

Adam Kilian

, 1923 - 2016

(Illustrator)

Adam Kilian was an eminent Polish scenographer, graphic designer and illustrator. He was originally from Lwów; during WW2, he and his family were deported to Samarkand. There, his mother founded Teatr Lalek Niebieskie Migdały [Puppet Theatre of Dreams]. In 1944, he enrolled at the Faculty of Architecture of the College of Arts and Crafts in Nottingham. After graduation, he came to Poland and devoted himself to theatrical scenography, co-creating many performances – children’s spectacles and puppet shows and operas and repertory theatre. At first, he worked for his mother’s Niebieskie Migdały Theatre in Warsaw, then in Teatr Lalka [Theatre “Puppet”] where during a 60-year artistic career, he created many performances inspired by folklore, folk art and/or naïve art.

He also frequently worked for adult audiences at Teatr Współczesny [Modern Theatre] in Szczecin, Teatr Powszechny [Theatre for All], Teatr Narodowy [National Theatre] and Teatr Polski [Polish Theatre] in Warsaw or Teatr im. J. Słowackiego [J. Słowacki Theatre] in Kraków. In total, he created 323 scenographies for theatres in Poland and abroad. He also designed scenographies for 22 television plays, as well as 72 cartoons and animated puppet films. He illustrated many children’s books and cooperated with Płomyczek [Flicker], a popular weekly magazine for children. In addition, he designed posters and postcards.

He received many awards for his contributions to Polish culture (see the list of his awards at culture.pl), including his favourite, Order Uśmiechu (The Order of the Smile), the international award granted by children to adults for bringing them joy.

Sources:

Adam Kilian at culture.pl (accessed: November 25, 2021);

Adam Kilian at filmpolski.pl (accessed: November 25, 2021);

Adam Kilian at encyklopediateatru.pl (accessed: November 25, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

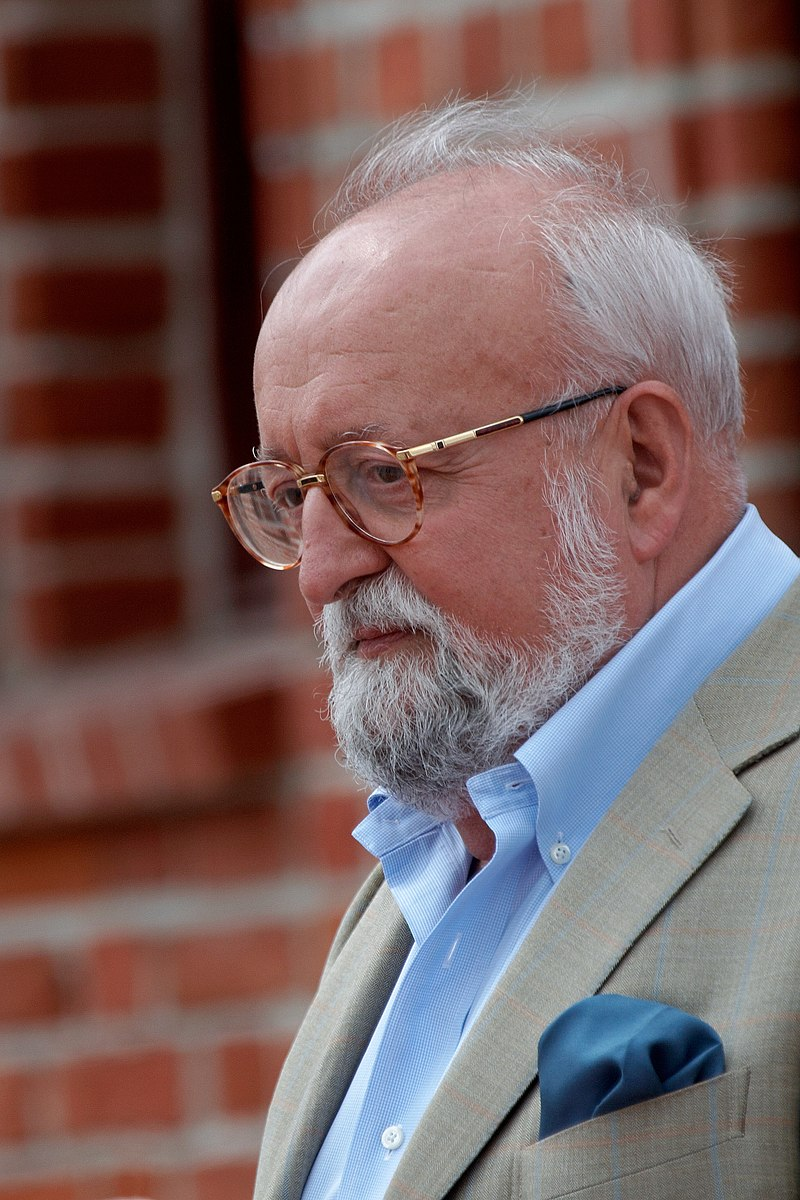

Retrieved from Wikipedia (accessed: February 25, 2022), author of the photo Adam Kumiszcza, CC BY 3.0 licence.

Krzysztof Penderecki

, 1933 - 2020

(Composer)

Official website (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Culture.pl (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Penderecki-center.pl (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Polmic.pl (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Wikipedia (accessed: February 25, 2022).

Summary

The animation begins with an image of King Midas in scarlet garments sitting on a throne, with a wide smile, counting gold coins. Behind the throne, a big round relief presents his profile as if it were part of a giant coin. Four maidens bring him gold objects, which make him content. His daughter comes to get a hug but is ignored. Instead, Midas approaches a golden jug, puts his gold in it and takes it to his basement accompanied by his guard. There, behind a round gate, he has his treasury. Inside the vault, he not only hides the jug inside a pithos but also enjoys himself by letting coins fall through his fingers. In another scene, the king’s daughter plays in the garden and picks flowers. When the girl comes up to her father to hug him, he suddenly takes her crown to place it in the vault with other precious items. While Midas is playing with his gold again, a golden god appears. Midas touches his staff and becomes as golden as the god himself. He is amazed by the transmutation and touches two pithoi which immediately become pure gold. Also, the gate turns into gold when Midas exits; he even leaves golden traces on the pavement. At night the monarch dreams about more money. The following day Midas’ golden touch still works – the curtains, a fly, a table, unfortunately, the food as well, everything turns into gold, even the princess and a guard. Midas gets so angry that he throws things and destroys a column. The god reappears and, with his staff, sends rain upon the ruler. The king’s golden image turns colourful again – Midas regains his scarlet coat and brown hair and beard. The god restores the broken column as well and disappears. The happy king goes to the enchanted garden, where he puts the crown on the head of the princess’ statue and finally hugs her. The girl is brought back to life, so the father picks her up and dances out of joy.

Analysis

This short animation retells the myth of Midas’ Golden Touch. This reinterpretation is about a lack of paternal love caused by an overwhelming interest in making and collecting money. The greedy King Midas, too busy with counting his treasures, cannot appreciate the family warmth, filial love, and overlooks the emotional needs of his daughter – to be loved rather than rich. The final moving scene confirms that the ruler eventually recognized and appreciated the value of his daughter’s presence, even if he could not grasp it before.

Though the animation is conventionally simplified, and some sub-plots of the myth are omitted (the motif of Midas’ hospitability towards Silenus which earned him the Golden Touch, the pleas to Dionysus to undo the gift, or the bath in the river Pactolus which cancels the curse), the elements of Antiquity introduced into the tale are numerous and very detailed. Even though the mythical Midas hailed from Phrygia, the animation creators used elements of pre-classical Greek Antiquity connected mostly with Cretan culture. Ornaments used on massive columns, pottery, and motifs on garments are undoubtedly Greek, although not classical, but rather archaic or combining elements from different ages, highlighting the distance to mythical times. The pottery style displays themes of the geometric period, thus even human and animal motifs, like chariots with horses and charioteers, are depicted geometrically. The servant maidens wear dresses resembling Cretan outfits and even walk with raised arms, in a pose known from terracotta and faience figurines, such as, for example, representations of the snake goddess from the Palace in Knossos.

As Midas’ addiction to gold is his main trait, the motifs from ancient coins are shown. A stone ring behind the throne is decorated with a relief of the king’s profile, which strongly evokes a coin’s obverse presenting an image of the issuer. Though made from gold, the coins he gathers strongly resemble the silver “owls” – Athenian tetradrachms – with quadratum incusum square imprint, featuring on the reverse, an owl, an olive sprig and initials ΑΘΕ (here AOE). Other coins have Midas’ profile on the obverse. Shields of the guards and the gate to the vault resemble ancient Greek coinage and its motives. To indicate the direction of the underground room, the vault’s gate is decorated with a coin motif used before (owl, olive sprig and letters ΑΘΕ) on the outside, and mormolyke – Gorgo’s face – on the inside, as the obverse of the earliest coinage of Athens and as the additional protection of the treasure. Also, the column destroyed by the king disintegrates into gigantic-sized gold “owl” coins.

Last but not least, an interesting reference to antiquity is the character of Dionysus. He is depicted in geometric style, in the same convention as the Cretan maids, and does not resemble his classical portrayals. His figure is effeminate, with a slim waist, long robes and long hair. He is, however, bearded and, for that reason, can be considered a male god. The only indication suggesting that he is Dionysus is the presence of the thyrsus, although it does not look like a pine-cone tipped staff with ribbons. Fortunately, the motif of a pine-cone and grapevine leaves appears on his hat, allowing the viewer to identify him as the god known from the myth about Midas.

The absence of dialogues highlights the role of sound effects and music, composed by Krzysztof Penderecki, and illustrates the film perfectly.

Further Reading

Bańkowski Antoni and Sławomir Grabowski, Semafor 1947–1997, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Studia Filmowego Semafor, 1999.

Ciszewska, Ewa, “Who Benefits from the Past? The Process of Cultural Heritage Management in the Field of Animation in Poland (The Case of the Se-Ma-For Film Studio in Łódź)”, Animation: an interdisciplinary journal 14 (2019): 117–131.

Kossakowski, Andrzej, Polski film animowany 1945–1974, Wrocław-Warszawa-Kraków-Gdańsk: Zakład Narodowy imienia Ossolińskich, Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1977.

Addenda

Production Team:

Director: Lucjan Dembiński,

Assistant Director: Ludwik Kronic,

Screenplay: Ryszard Brudzyński,

Music: Krzysztof Penderecki,

Sound: Jan Radlicz,

Design: Adam Kilian.