Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

Samuel E. Krune Mqhayi, Ityala Lama-Wele. Lovedale, South Africa: Lovedale Press, 1914.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Ityala Lama-Wele at the New African Movement website (accessed: April 13, 2022).

Genre

Novels

Target Audience

Young adults

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Eleanor A. Dasi, The University of Yaounde I, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Divine Che Neba, University of Yaounde 1, nebankiwang@yahoo.com

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaounde 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

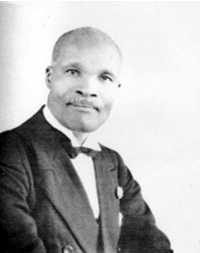

Retrieved from Wikipedia (accessed: April 13, 2022). Public domain.

Samuel Edward Krune (SEK) Mqhayi

, 1875 - 1945

(Author)

Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi was born on December 01, 1875 in Gqumahashe village Cape Town South Africa. He spent the greater part of his years in the rural Transkei district, and this is thought to have contributed in his love for Xhosa language and poetry which eventually earned him the title of “the father of Xhosa poetry”. He was educated in Lovedale Public TVET College, where he took a diploma in teaching. Aside from being a poet, he was also a novelist, dramatist, historian and translator. He is known for his works such as U-Samson, Don Jadu, and Abanta Besiwe. He wrote The Lawsuit of the Twins in defense of Xhosa law. He died in 1945.

Source:

Britannica (accessed: August 20, 2020).

Bio prepared by Eleanor A. Dasi, University of Yaounde I, wandasi5@yahoo.com

Adaptations

Adapted for a popular television drama in the late 90's, directed by Zinzi Zulu, SABC.

Translation

English: The Lawsuit of the Twins, trans. Thokozile Mabenga, South Africa: Oxford University Press, 2018, 83 pp.

Summary

Succession and the justice system of Africa woven with the ethos and mores of the Xhosa people of South Africa thrills the narrative of The Lawsuit of the Twins. The story is about a dispute over inheritance between twin brothers and the eventual collapse of a clan due to colonial invasion. The plot unfolds with a court case between the twin brothers, Wele and Babini, the younger and the older brother respectively. While Babini thinks he is the rightful heir to the homestead by virtue of his seniority and as custom demands, Wele on his part thinks his elder brother is irresponsible; had sold his birth right in exchange for a bird and has continued to sell the cattle of his late father. Wele considers himself an heir who has proven himself by his actions cleaning up the mess of his elder brother particularly when the elder brother went against the custom of performing the cleansing rite after the death of their father, Vayisile. Wele believes that his actions legitimise his position as heir and so he drags Babini to court for the second time after defying the previous verdict of Lacangarana, the quarter head. After the hearing, which involved many testimonies, the people of Tshiwo Kingdom are still faced with the dilemma of awarding inheritance. Among these testimonies is that of the eldest midwife, Teyase, who assisted their birth and claimed that one of the twin’s hands came out first and the top joint of the little finger of this hand was cut to identify him as the senior, but the hand went back inside and mysteriously, the twin who finally came out first had all his fingers in place*. This complicated matters the more as the question still stands as to whether they should base it on seniority or on actions taken for the general good of the land. The king and the council of elders are unable to agree on the verdict and therefore decide to seek help from Khulile, the high king.

Khulile, the high king, ends up acknowledging the seniority of Babini but, however, he hands down responsibility of Vayisile’s homestead to Wele while requesting Babini to continue to support his brother. The twins agree to this and start working together and gradually Babini starts becoming responsible. Later, it is announced that the king plans on visiting Vayisile’s family for the consolation rite of their late father. This cannot be carried out without knowing who is the real heir of the homestead. The village goes into confusion for fear of another unending lawsuit but this time Wele willingly cedes power to his elder brother and both continue to work for the good of their homestead. Not long after, Khulile passed on to glory and the nation is plunged into chaos due to intertribal wars and colonial invasion. The story ends with the praise poet’s song predicting doom and the disintegration of the Xhosa Nation. He asks them to be alert because evil is fast encroaching on their land; there will be bloodshed, animosity, father against son, son against father and an end to humanity. He ends with a cry: “My father! My father! My lord! My lord!” (78). The king and all the people, even the praise singer himself wept at the fall of their fatherland.

* In most African cultures, when twin children are being born, a mark is put on the one that comes out first to show that he/she is the senior.

Analysis

Inheritance and leadership are central to The Lawsuit of the Twins as in most world mythologies preoccupied with origins. The story depicts a traditional South African society where the laws of the land fail to resolve the riddle surrounding inheritance. Torn between granting inheritance based on responsible actions or on seniority, the kingdom remains agitated. Disputes always surface whenever there is a contestation of the law. The Xhosa law stipulates that inheritance is based on seniority. However, the fact that Babini sends out his hand from the womb first, and is given the mark of seniority (cutting off his finger), but yet it is Wele who finally is born first, indicates a message from the ancestors. This message probably states that one who goes against culture is not fit to hold any position of responsibility in the land. Thus Wele wins the people’s favour because of his sense of responsibility and his adherence to the ways of the land. That notwithstanding, both brothers’ acknowledgement of the other’s strength shows humility, which helps them manage their homestead well.

The voice of the praise poet is given a metaphysical dimension. It saddens the whole tribe to learn of the tragedy that awaits them. This presentation of the praise singer is a regret at the dying tradition of the Xhosa people (the loss of the values that held them together) due to colonial/foreign invasion.

Further Reading

Dada, Lubabalo, Ityala Lamawele celebrates 100 years, SABC News, 18 Sept. 2014 (accessed: April 13, 2022).

Dikeni, Clifford, An examination of the socio-political undercurrents in Mqhayi's novel "Ityala lamawele", (thesis/dissertation) University of Cape Town Faculty of Humanities African Languages and Literatures, 1992.

Engelbrecht, Scina M., Challenges in cross-cultural translation: a discussion of S.E.K. Mqhayi's "Ityala Lamawele", (thesis/dissertation) Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal, 2002.

McDonald, Peter D., “Literary Space/Creative Practice: Reading Ityala Lamawele in English Today”, Text and Reception in Southern Africa 33 (2021): 44–49.

Mdlangaso, N. I. E., Study of law and order in S E K Mqhayi's works with special reference to "Ityala lamawele", Alice: University of Fort Hare, 1976.

Mtumane Z., “The Practice of Ubuntu with regard to amaMfengu among amaXhosa as Depicted in S. E. K. Mqhayi's Ityala Lamawele”, International Journal of African Renaissance Studies 12. 2 (2017): 68–80.

Nyamede, Abner, “The conception and Application of Justice in S. E. K. Mqhayi’s Ityala Lamawele”, Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 47(2), 2009: 19–30.

Peires, Jeff, “Lovedale Press: Literature for the Bantu Revisited”, English in Africa 7 (1980).

Tebbe, Nelson, “Inheritance and Disinheritance: African Customary Law and Constitutional Rights”, The Journal of Religion 88.4 (2008): 466–496.