Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

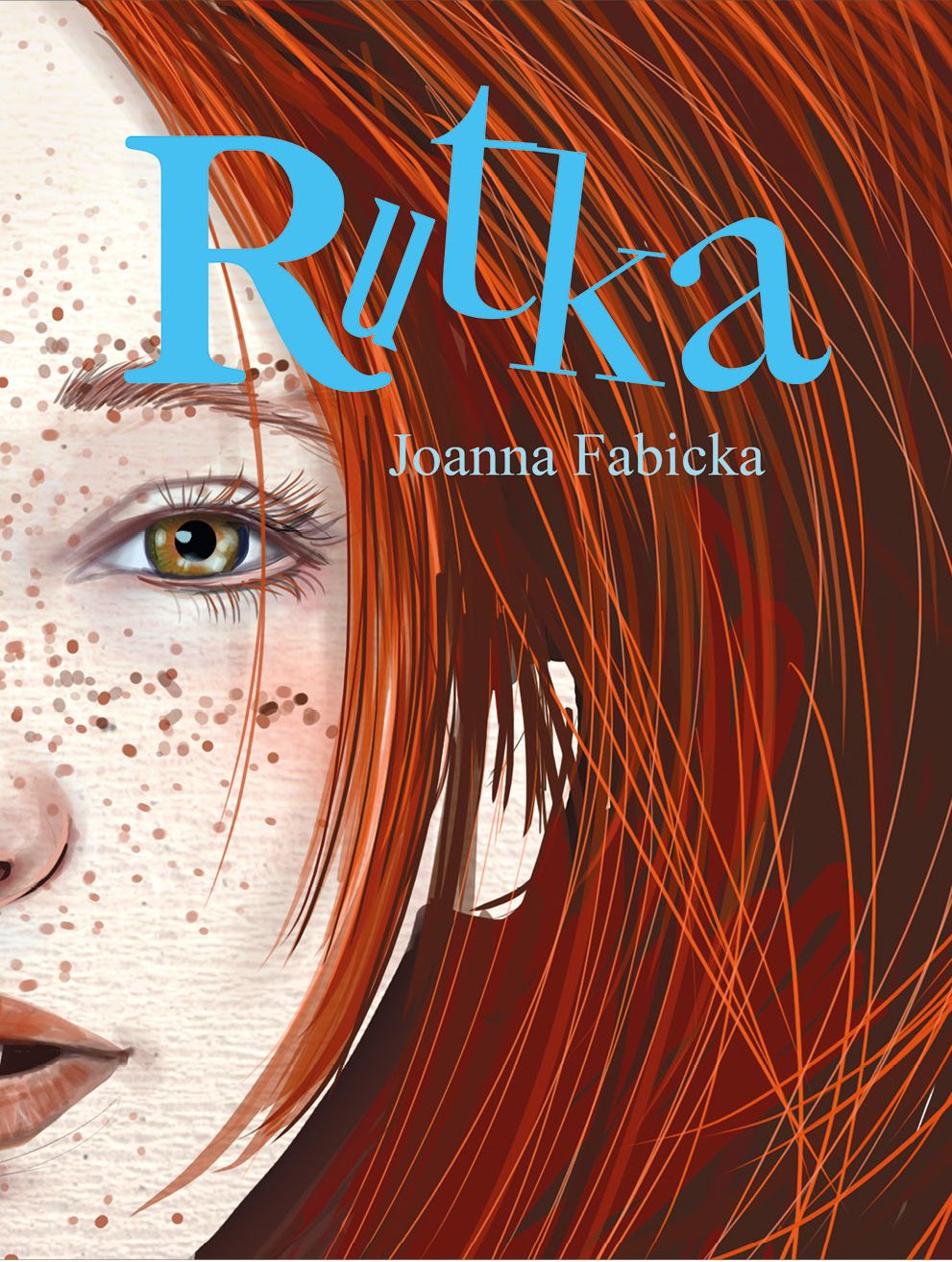

Joanna Fabicka, ill. Mariusz Andryszczyk, Rutka. Warszawa: Agora S.A., 2016, 224 pp.

ISBN

Awards

2016 – main literary award and the title of the “Book of the Year” for young adults awarded by the Polish Section of IBBY;

2017 – nomination for “Gryfia Literary Award for a Female Writer” (the only children’s book to date nominated for this award);

2017– “White Raven” status, awarded by the International Youth Library in Munich.

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Magic realist fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (Children and young adults – according to the Polish Section of IBBY: 12+)

Cover

Courtesy of Agora S.A.

Author of the Entry:

Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Portrait by Paweł Kiszkiel, courtesy of the Author (Joanna Fabicka).

Joanna Fabicka

, b. 1970

(Author)

A writer, poet, scriptwriter, film editor born in Łódź, Poland. She graduated in film studies from at the University of Łódź, with a thesis on the motifs of the double and the magic murder in Elisa, vida mía [Elisa, My Life] (1977) by Carlos Saura. When working at the Leon Schiller National Higher School of Film, Television and Theatre in Łódź, she edited Sławomir Fabicki’s (her husband’s) Oscar-nominated short movie Męska sprawa [A Man Thing] (2001). She has written many books both for adults, such as Idę w tango. Romans histeryczny [I’m Going on a Bender: A Hysterical Romance] (2008) and Second hand (2013), as well as for children and young adults. Her most popular works in this field are the Rudolf Gąbczak series (the first volume published in 2002, the last to date – in 2017), which has been compared to Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole books, and the critically-acclaimed novel Rutka (2016). Her books have been translated into Russian, Czech, and Ukrainian. She is an admirer of pure nonsense. She has said that if she were not a writer, she would be a chef in her own restaurant, and that in her next life, she would wish to work with young people as a therapist. She has two daughters and currently lives in Warsaw.

Source:

Bio based on information kindly provided by the Author.

Bio prepared by Maciej Skowera, University of Warsaw, mgskowera@gmail.com

Summary

In contemporary Łódź, in the district of Bałuty,* a girl named Zosia Sardynka is going to spend the last days of the holidays without her mother. The woman leaves the city every year in order to work elsewhere and her daughter has been under a neighbor’s care all the previous years. However, the summer we read about is different, as an eccentric aunt Róża comes to the tenement house where the protagonist lives. The woman has a great deal of money, but does not care about it; she moves in a wheelchair and smokes a pipe, and she can spit watermelon seeds from her ears – and soon she befriends Zosia.

From the moment the aunt arrives, the diegetic world of the novel, initially presented as realistic, starts becoming more and more magical. All of a sudden, Zosia meets a girl approximately her age – a redhead – a lively, spontaneous girl called Rutka. The protagonist’s new friend lives alone in an empty house, where only contours of people, drawn with a piece of chalk, serve as a reminder of Rutka’s family, who went in an unknown direction – the girl thinks that they are on the “Diamond Planet.” Zosia learns that her companion must hide to avoid people’s dangerous gazes, sees strangely dressed men and women getting into train wagons, and visits a market where she cannot pay for food using contemporary money. As Anna Pekanies notes, “the younger reader would see the more and more complicated plot’s peculiarity, while the adult one would understand that Zosia moves from the 2nd decade of the 21st century to Łódź during WW2, to the ghetto.”** However, the girls’ oneiric time travel is a two-way trip, as Rutka also wanders through contemporary Łódź, not seeing people and places she knows, but visiting, inter alia, a popular discount grocery store “Biedronka.”

When Zosia’s mother is back, Róża prepares a Shabbat supper. During the meal, the girl argues with her mother, who is not able to see Rutka and mocks her daughter’s words. Zosia becomes ill, but she gets well soon, and together with Róża and Rutka visits the Radegast train station – a place that, during WW2, served as a starting point of the Holocaust transports, and now is a museum and memorial site. Here, Zosia – to her surprise – sees objects from Rutka’s house, while Rutka finds a photograph of her family. She sinks into the picture, reunited with her close ones. The next day, Zosia cries when the rain washes the last signs of Rutka’s existence away. Róża comforts the girl: “You can hide anything you want in your heart. (…) Remember, it’s the best safe in the world. (…) Rutka will always be with you.”*** When Zosia asks where her friend really is, her aunt answers: “In our memory.”**** In this very moment, as the last sentence of the books informs us, “Zosia realized who was the person whom she met this sultry, mysterious summer.” *****

* Bałuty is a district in Łódź where part of the Litzmannstadt Ghetto was located.

** Anna Pekaniec, “Dwie opowieści o wojnie, Holokauście i nie tylko. Kotka Brygidy Joanny Rudniańskiej i Rutka Joanny Fabickiej” [Two Stories about War, the Holocaust and More: Joanna Rudniańska’s Brigida’s She-Cat and Joanna Fabicka’s Rutka], Czy/Tam/Czy/Tu. Literatura Dziecięca i Jej Konteksty 1.2 (2017): 8–29, 17; the quotation translated by Maciej Skowera.

*** Joanna Fabicka, Rutka, ill. Mariusz Andryszczyk, Warszawa: Agora S.A., 2016, 218; all quotations from the book translated by Maciej Skowera.

**** Fabicka, Rutka, 219.

***** Fabicka, Rutka, 219.

Analysis

During their peregrinations through Łódź as it was in the past, Zosia and Rutka encounter a character called the White Man. Rutka tells her friend that it would be best never to meet him, and the narrative soon suggests why. The protagonists see him next to the railway ramp where people, crying in despair, wait to board the wagons. The White Man opens one of the wagons, from which a swarm of multi-coloured butterflies fly out. He tries to catch them using a butterfly net and, eventually, starts to devour the insects. Zosia and Rutka attack the White Man, so the butterflies can be safe. The girls encounter this character one more time, when he dies being struck by lightning.

The White Man, as Anna Pekaniec indicates, “(…) is Chaim Rumkowski – a man who, during WW2, was the head of the Litzmannstadt Ghetto’s Council of Elders and a particularly tragic figure because of his actions in the time of the operation “Wielka Szpera” [Aktion Gehsperre – “Great Search”].* Rumkowski, in his speech Give Me Your Children, delivered on September 4, 1942, said: “A grievous blow has struck the ghetto. They are asking us to give up the best we possess – the children and the elderly. I never imagined I would be forced to deliver this sacrifice to the altar with my own hands. In my old age, I must stretch out my hands and beg. Brothers and sisters: Hand them over to me! Fathers and mothers: Give me your children!...”**

In this context, the White Man can be also interpreted as a figuration of Greek Kronos/Cronus, identified with the Roman Saturn. In Greek mythology, “in fear of a prophecy that he would in turn be overthrown by his own son, Kronos swallowed each of his children as they were born,”*** later was forced by Zeus to regurgitate them and, then, imprisoned. As the head of the Jewish people, the White Man/Rumkowski, eating the butterflies that symbolize people killed during the Aktion Gehsperre, is similar to Cronus devouring his own children. Interestingly, the fact that he eats winged insects makes him similar, too, to el Hombre Pálido [the Pale Man], a blind monster which appears in Guillermo del Toro’s film El laberinto del fauno [Pan’s Labyrinth] (2006). In this film, the Pale Man is a terrifying creature who eats children and winged fairies. Joanna Aleksandrowicz sees el Hombre Pálido as an incarnation of Saturn, as presented on Francesco Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring His Son (c. 1819–1823).**** What is more, there is also a reference to the Holocaust in the scene in which the monster appears: in the chamber where the Pale Man resides, a pile of children’s shoes and a furnace resembling a crematorium furnace can be seen.

* The word “Szpera” derives from German “Allgemeine Gehsperre” meaning a general curfew, a ban on leaving homes. The Aktion Gehsperre started on September 5, 1942 and ended a week later. Houses in the Ghetto were searched by Jewish policemen and German gendarmes in order to find all the elderly, ill and infirm people and children under 10 years old. More than 15 000 people were sent to an extermination camp in Chełmno upon Ner [Kulmhof]. In addition, many people were killed because they refused to part with their families. Very few children under 10 (those who managed to hide and the children of Jewish superior officers and policemen who took part in the Aktion Gehsperre) survived these events, according to: Joanna Podolska, Łódź żydowska. Spacerownik [Jewish Łódź: A Walking Guide], Łódź: Agora S.A., 2009, 124–125.

** Transcript for Give Me Your Children: Voices from the Lodz Ghetto, available online at ushmm.org2 (accessed: September 25, 2018).

*** Kronos, available online at theoi.com (accessed: September 25, 2018).

**** See: Joanna Aleksandrowicz, “Saturn Goi – przeobrażenie mitu” [Saturn of Goya: Transformation of the Myth], Transformacje 1–2(80–81) (2014): 110–129, pp. 125–127.

Further Reading

Aleksandrowicz, Joanna, “Saturn Goi – przeobrażenie mitu” [Saturn of Goya: Transformation of the Myth], Transformacje 1–2(80–81) (2014): 110–129.

Kronos, available online at theoi.com (accessed: September 25, 2018).

Pekaniec, Anna, “Dwie opowieści o wojnie, Holokauście i nie tylko. Kotka Brygidy Joanny Rudniańskiej i Rutka Joanny Fabickiej” [Two Stories about War, the Holocaust and More: Joanna Rudniańska’s Brigida’s She-Cat and Joanna Fabicka’s Rutka], Czy/Tam/Czy/Tu. Literatura Dziecięca i Jej Konteksty 1.2 (2017): 8–29.

Podolska, Łódź żydowska. Spacerownik [Jewish Łódź: A Walking Guide], Łódź: Agora S.A., 2009.

Slany, Katarzyna, “Rutka Joanny Fabickiej jako przykład postpamięciowej literatury dla dzieci” [Rutka by Joanna Fabicka as an Example of Post-Memory Children’s Literature], Maska 3.35 (2017): 81–94.

Transcript for Give Me Your Children: Voices from the Lodz Ghetto, available online at ushmm.org (accessed: September 25, 2018).

Copyrights

[Fabicka’s portrait] Portrait by Paweł Kiszkiel, courtesy of the Author (Joanna Fabicka).

[Cover] Courtesy of Agora S.A.