Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Ursula Dubosarsky, The Boy who could Fly: Eleven plays for children inspired by stories from the Metamorphoses of Ovid. Independently Published, 2017, 160 pp.

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Play*

Target Audience

Children (Intended for primary school children)

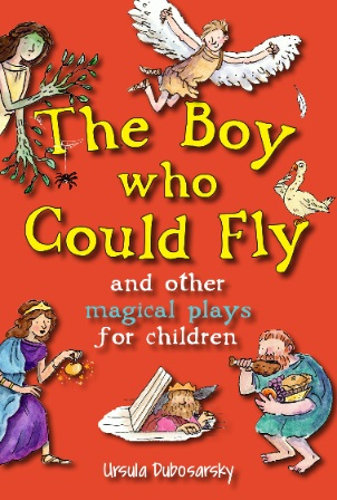

Cover

Cover from the second edition (2019), courtesy of Christmas Press, the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Allison White, University of New England, awhite55@une.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Ursula Dubosarsky

, b. 1961

(Author)

Ursula Dubosarsky is an Australian writer of children’s and young adult fiction. Born in Sydney in 1961, she received an education in classical languages and literature at the University of Sydney (1982). She has a PhD in English Literature from Macquarie University (2008). She travelled to Israel and worked on a kibbutz, where she met her Argentinian husband. Her work is influenced by her travel, by an enjoyment of word play, intertextual referents, and an empathy with her child characters. Her child characters tend to be intelligent, intense, and observant loners. She is also very fond of guinea-pigs, which appear in many of her works.

Source:

Official website (accessed: September 4, 2020).

Bio prepared by Margaret Bromley, University of New England, brom_ken@bigpond.net.au and Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing/working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

Well, things you read stick in your mind as a writer and I suppose you store them away for the future, without conscious intentions. I loved the tone and energy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses from my very first reading when I was 12 in a Year 8 Latin class, translating the Pyramus and Thisbe episode and then the story of Io. I found them enchanting, unsettling and very funny. They were not stories I had ever read before.

At much the same time as I was reading the Metamorphoses I also saw a school French production of Jean Anouilh's Antigone which made an enormous impression as a work of art; then a couple of years later I saw another school production of Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld. A very different approach to Anouilh! and yet the works have much in common, in their apprehension of the classical world, not something alien and distant from modern society, but endlessly resonant. Then we read A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and another extremely entertaining incarnation of Pyramus and Thisbe. I’m sure all these works, all written for stage, were fundamental to my choice of Ovid when I was asked, 35 years later, to write some plays for primary school children for the NSW School Magazine.

I was under a certain constraint with the plays, particularly in regard to the sexual activity which is central to several of the stories, as the School Magazine is an official publication of the NSW Department of Education. There was some concern from higher up in the Department (not the Magazine itself) from the very first play, "Io, the Girl who turned into a Cow" – it was felt to be crossing the line of decent behaviour and a bad model for children. There was a meeting called, and a discussion held, but in the event the play was published without alteration, and no objections were raised to further plays.

In the novels, Theodora’s Gift, How to Be a Great Detective, Black Sails White Sails, The Golden Day and The Blue Cat, for the most part the classical myths are adapted almost secretly – the reader often may have little idea that I am working from a classical story, which they may or may not be familiar with. It is almost something that feeds me as a writer, than helps me find mirrors of meaning, watery shadows deep under water of centuries of human storytelling. The same is true of the use of Biblical stories in The First Book of Samuel and again Theodora’s Gift, which draws on both Biblical and classical mythology.

2. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I did six years of Latin at high school, then another two years of Latin and two years of Greek at Sydney University. But my pleasure has always been literary and not scholarly – I read the works as a reader and a writer, not a scholar. Later in life I have joined Latin reading groups, through organisations such as the Workers Educational Association. As a writer I suppose I prefer to respond directly to the texts, word for word, as works of literature, as one reader to another, without mediation.

Courtesy of the Author.

3. How concerned were you with "accuracy" or "fidelity" to the original? (another way of saying that might be — that I think writers are often more "faithful" to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail — is this something you thought about?)

I certainly did think about it when I was writing the plays, and I worked all the time with the original Latin texts, hoping to include as much detail as possible. But what I wanted most of all was to give children a sense of what the experience of reading Ovid might be like, that they would come away from the plays with an impression that these are not heavy, ponderous works, but witty, light, accessible and at the same time strange, dramatic and surreal. My primary motive is that children will have the pleasure of reading in the moment, but I’m also hoping that when they see the name Ovid anywhere in the future that they will associate it with laughter and wonder – and that they may be drawn to read more.

4. Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

Not specifically, but as you can see, I think I can’t help myself! The literature of the classical world seems inseparable from the way my mind works as a writer. I’m sure there will be more …

Prepared by Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Summary

Originally written as short plays for the New South Wales School Magazine, these stories are based upon a selection of myths in Ovid’s epic Metamorphoses. In Dubosarsky’s collection, she includes 11 short plays:

Icarus: The Boy who could Fly – Icarus’ father, Daedalus, makes them both wings of beeswax and feathers so that they can fly back to Athens. Daedalus warns Icarus not to fly too close to the sun or the water, but to take the middle path. The boy does not listen but flies closer and closer to the sun until the wax on his wings starts to melt and he tumbles into the sea.

Pygmalion: The Statue who came to Dinner – Pygmalion is a lonely man who is in love with a white, ivory statue which he has himself carved, named Galatea. When Pygmalion attends a festival, he requests Venus to make his statue come alive. His wish is granted and he returns home to find his Galatea is living flesh and blood.

Echo and Narcissus: When the girl who talked too much met the boy who loved himself – Echo is cursed by Juno and is only able to echo others’ words. She meets Narcissus (a very, very handsome boy) and tries to befriend him. Instead, Narcissus is distracted by the boy whom he can see in the water. He falls into the stream and disappears, but Echo is unable to tell his mother where he has gone.

Arachne: Spider Girl! – Arachne, a very talented but arrogant weaver, challenges Minerva (the goddess of wisdom) to a weaving contest. They both weave their own tapestries which are equally beautiful. Minerva is unnerved by Arachne’s rude attitude and turns her into a spider.

Erysichthon: The very very very very VERY Hungry Man – Erysichthon cuts down a tree (one that is beloved by the goddess of harvest, Ceres) and uses the wood for a fire. Ceres is outraged and orders Hunger to breath on Erysichton so that his hunger is never satisfied. Erysichton then embarks on a search for more and more food.

The Story of Io, the girl who was turned into a Cow – The young girl, Io, loves running from her father into the woods. One day she is met with Jupiter who himself is running away from his wife, Juno. When Juno appears, Jupiter panics. Not wishing to be found in the company of another woman, Jupiter turns Io into a cow.

Daphne and Apollo: The boy with the Golden Arrow – When a child mocks Cupid’s golden and black arrows, he demonstrates what they can do. With the golden arrow, Cupid strikes Apollo so that he falls in love with a young girl, Daphne. With the black arrow, Cupid shoots Daphne with the black arrow – making her impervious to any kind of love. Apollo follows her endlessly, but Daphne remains uninterested.

Philemon and Baucis: The Goose who was very nearly cooked – Jupiter and Mercury decide to go under-cover as ordinary people. They go around to various houses to stay the night but are met with rejection until they come to the house of Philemon Baucis, and their pet goose. When the couple realise that they are entertaining two gods, they decide to prepare their pet goose to serve it for dinner.

Theseus and Ariadne: the a-mazing ball of red wool – Theseus goes into the Minotaur’s Labyrinth to slay the Minotaur, and Ariadne weaves him some special red wool so that he won’t get lost.

Atlanta: The Fastest Girl in the World – Atlanta, a very fast runner; does not wish to get married so she tells her father that she will only marry the man who can beat her in a race. Hippomenes soon falls in love with her, and with the help of Venus, manages to beat her in the race.

King Midas and the Whispering Grass – King Midas judges a flute-playing contest between Pan and Apollo, but angers Tmolus (the mountain god) with his verdict. Tmolus curses him with donkey’s ears and King Midas hides them under his turban. When his servant, Petronella, discovers that he now has ears, she is desperate to tell somebody – so she whispers it only to the grass.

Analysis

Each of these myths have been retold in a fun, and clever style which is entertaining for both children and adults. The plays are filled with sarcastic and humorous overtones, some of which would only be picked up by adults. In Pygmalion: The Statue who came to Dinner, Pygmalion talks to the white statue ‘Lucky I’ve got you, Galatea darling. So sensitive, so gentle. You never raise your voice, or giggle, or argue’ (unpaginated). The play pokes fun at the desperate actions of Pygmalion (being in love with a statue), though the humour here is likely lost on a younger audience. The stage directions are lively and engaging. They are intended to be performed by school children, and possibly older students who have an interest in Greek or Roman Mythology, provided as supplementary reading material for young students (a particular aim of the New South Wales School magazine).

The individual plays retain their plots as they appear in Ovid’s epic, but at times the stories are altered to suit a younger audience. For example, Echo does not appear to be in love with Narcissus, but rather meets him in hope of having a play-mate. In Theseus and Ariadne, the story ends with Ariadne sailing away with Theseus – though the narrative mentions her ‘dreaming’ that she will go up into the sky. In this case, Dubosarsky only hints at what comes after (that Theseus will abandon Ariadne), but it is not explicit in the text. Likewise, in Pygmalion and Galatea, the story tells of his statue, Galatea, who comes to life through the powers of Venus. Once living, Pygmalion and Galatea celebrate with a dinner – a slightly less erotic celebration than the one described by Ovid. The morals of Ovid’s stories are sometimes quite ambiguous. Arachne, while hubristic, lives up to her claims of being a great weaver and her work is of equal quality to Minerva’s. The god’s punishment of Arachne then looks like jealousy, rather than simply punishing her for her audacity. Similarly, Io is transformed into a cow simply because of her looks. Just as Daphne is saved from rape only by being transformed into a laurel tree. There is no justice or moral in these stories from the perspective of the maidens. It is likely that Dubosarsky aims to retain this amoral tendency of the original stories.