ACCLAIM Interviews: Dr Cora Beth Fraser

Hello everyone, I am Adam Soyler I am a student at Roehampton university studying history. One of my modules required me to find a work placement. While looking for a placement I came across the Autism and Classical Myth project which uses classical mythology to help and stimulate autistic children in line with the Our Mythical Childhood project and the ACCLAIM Network. The project offered me a work placement and one of my tasks was to interview members of the Network. I hope you enjoy the questions and answers that were produced!!!!

In April 2021, I interviewed Cora Beth Fraser who teaches Greek and Roman Myth (among other topics) at the Open University. Cora Beth has always been interested in the intersection of Classics and Education. She graduated from Newcastle University in 2005 with a PhD in Classics, and gradated at the same time from the Open University with an MEd specialising in Primary Education. Cora Beth now has a third master’s degree too, with a particular focus on online accessibility. She is currently very actively interested in autism and learning.

Cora Beth outside Arbeia Roman Fort, which she is lucky enough to have on her doorstep.

Hello Cora Beth. My first question is: What got you interested in Greek and Roman mythology?

I don’t think there was ever a time that I wasn’t interested in myth – but it wasn’t specifically Greek and Roman myth. It was any form of fantasy literature. When I was a child, the world didn’t make much sense to me: people behaved in ways that I couldn’t explain, and I could never quite seem to do the things that they did, no matter how much I tried to mimic them. Fantasy worlds were easier: they had their own internal logic which was always set out for the reader. Magic had consequences; wishes were to be phrased carefully; names had power. Once you knew the underlying principles you could see patterns of cause and effect. I didn’t think like that at the time, of course; I was just drawn obsessively to books set in other worlds and other times, and was lucky to have family who reminded me to eat and sleep and leave my room once in a while!

It wasn’t until I was much older that I found out that becoming deeply absorbed in a fantasy world is a common autistic behaviour, particularly in girls. All I knew was that within a wholly fictional world it was much easier to understand the rules – even when those rules seemed capricious and unfair, as they so often do in classical mythology.

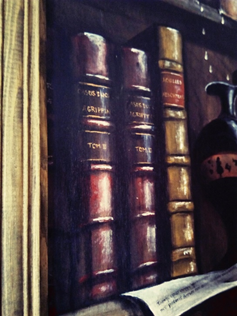

The books I valued most, growing up, were the illustrated ones, particularly the ones with complex illustrations that I could keep coming back to whenever I had a new insight. I learned a lot about many different illustrators, Walter Crane being perhaps my favourite, in his illustrations for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Wonder-Book for Girls and Boys and Tanglewood Tales. I create my own illustrations now, for my son, and as a form of relaxation; it’s an activity that reminds me of simpler times!

One of my own myth-inspired illustrations.

What interests you about autism?

My son is autistic, and I’m autistic myself. I had no idea that I was, for most of my life; I never really thought much about autism, but if I did, I certainly never thought that it had anything to do with me. I was just a regular person. True, I couldn’t do all the amazing things that other people somehow managed to do – like ride a bike, or eat vegetables, or say things that weren’t true. And I could do things easily that seemed to puzzle other people – remember random facts, for instance, or understand animals, or focus on a code or puzzle with complete intensity until it suddenly clicked. Those things were just quirks, I thought, and I’d learned to keep quiet about them in order to fit in.

It wasn’t until my son was a year old that I started to learn more about autism, through watching him develop in ways that were different from the other children around him. He didn’t respond to his name; he wasn’t learning to speak; he couldn’t cope with being looked at by strangers. By the time he was two, he was so frightened of people that I couldn’t even take him outside for a walk around the block. The expectations and the sensory input of the world around him were too much for him to handle.

I learned, alongside my son, how to see the world through the eyes of an autistic person – and it made me realise how hard I’d been trying all my life to suppress and regulate my own response to the world. I referred myself to an Adult Autism Diagnostic Centre, and wasn’t at all surprised to be told that I was most definitely autistic. It came as a tremendous relief, actually; it seemed like an acknowledgement that all the things in myself which I had seen as broken or weird were actually just fitting a different pattern.

What’s the best thing about teaching that you enjoy?

I like to share the things that make me happy. That’s a very simplistic view of teaching, I know: but it’s what motivates me. It’s not that my teaching always focuses on pleasant material, of course: I cover slavery and violence and cruelty and all the other horrific things that people who study the ancient world confront every day. But I find joy in words, and in making connections between texts, and in framing something so that it makes sense in a new way. Teaching, for me, is simply about sharing that feeling of excitement with others. When I get to speak to a class – in person or online – I usually have a long list of things I want to share, but somehow I never get to the end of it, because new things come up as we’re talking, and we go off in an entirely different direction...!

Teaching for me is an adventure: exciting and unpredictable, with an unknown destination. I'm not sure whether that makes me a good teacher, but I hope it makes me an interesting one! It meant a lot to me to win the Open University’s Recognition of Excellence in Teaching last year: it felt like an acknowledgement that, even though it can be hard for me to communicate with people, I might be on the right track as a teacher.

In your mini biography on the ACCLAIM website it says that you teach “Greek and Roman Myth (among other things).” what are those other things that you teach or enjoy?

At the moment I teach Latin, Roman history, Greek and Roman myth and a bit of archaeology, to adult distance learners – undergraduates and postgraduates – at The Open University. In the past I’ve taught Ancient Greek, Classical Civilisation topics, Ancient History more generally, and Arts introductory modules (including Music, English, Philosophy, Art History, Creative Writing and all kinds of other exciting things!).

I’ve also worked as a teacher of Fine Art in community centres. I used to be a mural painter, and when time allows I enjoy nothing better than transforming a blank wall into an imaginary bookcase or a doorway into another world!

A detail from one of my Library of Lost Works murals, featuring Agrippina’s lost memoirs and the missing Achilleis trilogy of Aeschylus.

How was your experience at Newcastle University and The Open University?

I’m a creature of habit; I find new things difficult. I could never face the idea of moving around the country, or the world, to chase work. I know my limits! So I went to Newcastle University for my first degree because it was my local university – no more than 10 minutes’ walk from my old school, in fact. And I stayed there after my BA, to do an MLitt and then a PhD, because I knew the place and the people and the rules – and all the best hiding places! After my PhD I even stayed on to do some teaching.

By that point, however, I’d discovered The Open University, and that changed a lot of things for me.

I started with the OU as a student, during the first year of my PhD at Newcastle. I’d been asked to teach a class in Ancient Greek at Newcastle, and I wanted to understand teaching, so I went looking for a course that would tell me what teaching was.

So in the first year of my PhD on Tacitus, I also picked up a Postgraduate Certificate in Professional Studies in Education from the OU, specialising in Applied Linguistics. More importantly, I’d discovered a way of studying – via distance learning – which removed all the social barriers that had made my life so difficult all through school and university. There was no going back for me! I picked up an OU Postgraduate Diploma the following year, focusing on Primary Education; then in my final PhD year I also completed a Masters degree in Education.

None of those courses actually did tell me what teaching was (that turned out to be a Socratic step too far for most MA programmes!) – but they did change my life. After I graduated – from Newcastle and the OU simultaneously – I immediately applied to be an Associate Lecturer at The Open University. It was the perfect job! I was able to teach from home, ‘meet’ new people without having to actually see them most of the time, work at my own pace (I like antisocial working hours!), and study courses for free with an annual fee waiver. Over the years I picked up several additional degrees and diplomas, all in different subjects. When I get a new prospectus I’m like a kid in a sweet shop! I have a magpie brain, drawn to new and shiny ideas, so I don’t suppose I’ll ever stop studying.

The OU gave me a job I could handle – and one I could enjoy, too. Most autistic people are not so lucky; the unemployment and underemployment statistics for autistic adults are shocking, and really highlight how much work needs to be done to promote accessibility and reasonable adjustments in the workplace.

How do you deal with autistic people’s difficulties when teaching?

I’ve learned a lot, over the years, from my autistic students – both about them and about myself. Some of the adult learners I work with now were diagnosed in childhood, so they know much more about autistic life than I do! But I’ve found that the challenges of working with autistic adults are entirely different from those faced by people who teach autistic children. Autistic children often need help to make sense of the world, and to find their place within it; they have so much to process when they’re growing up. Autistic adults have been through all this; they know what they want and need, and they also know what they need to avoid. Most of their difficulties are caused not by a ‘disability’ in the abstract, but by needs which are not being met.

So I’ve learned to let autistic students take the lead, in the sense of asking them what they need, listening to their responses, and doing what they tell me to do. If an autistic student tells me that they don’t like to talk on the phone, then we will never talk on the phone. If deadlines are a pressure they can’t handle, then we get rid of the deadlines. If they need certainty that they’re on the right track before they write an essay, then they submit a plan first. If they want to attend tutorials but can’t speak, then I will make sure that they’re never called upon to say anything.

Once the difficulties caused by external pressures are removed, by and large, autistic students don’t have difficulties; in fact, they tend to excel. As a teacher I love working with autistic students, because so many of them share my delight in learning!

I wrote some guidance recently for teachers working online with neurodiverse student groups. This is part of a much bigger project which I would love to develop further someday. Sadly my work has been teaching-only for the last 15 years, so I have very limited time for major research projects!

What makes the CUCD EDI Committee special?

The CUCD EDI Committee is new. We’ve only met a couple of times, and we’re still working towards a sense of our place in the wider academic community. But already the Committee has been working to amplify voices, to collect data, to publish work in all kinds of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion areas (including autism in universities) and to bring together EDI officers from Classics departments around the country. The hope is that the Committee will become a force for positive change – and I’m hoping to be able to help with that!

How has covid affected your style of teaching? Have there been any new techniques you may have used because of the pandemic?

That’s an interesting question! It would be reasonable to assume that there hasn’t been much effect on my teaching at all, since I was a distance-learning tutor before the pandemic, and am still teaching in much the same way. But there have been some big changes. One is that I haven’t had a chance to meet my students at all in over a year; and while our face-to-face events weren’t very frequent before the pandemic, they were much valued, both by me and by the students, as a chance to connect on a more personal level. It’s been interesting, because it’s made me realise that I’m not nearly so averse to in-person teaching as I sometimes think I am! I miss the pure enjoyment of being in a room full of people who are all interested in the same things as I am.

During the pandemic I’ve also been making the most of online tools. Twitter has been a wonderful resource – it's helped me to connect with other people in Classics, but it’s also been a way of staying visible and approachable to my students. It’s not a replacement for meeting them, but it’s something.

I’ve also been using my personal website, Classical Studies Support, as a way of connecting people during the pandemic. I developed the website several years ago with my autistic students in mind, as a way of connecting with the people who didn’t want to take part in forums and organised activities; I have strong views about the rhetoric of ‘participation’ and ‘active learning’ in Higher Education, and wanted to push back against that by creating a low-pressure community of readers and occasional contributors. To that end, I’d been posting a weekly newsletter, with some Classics-related chat and links for further reading, to several hundred followers, mostly students. When the pandemic started to restrict people’s opportunities to connect in traditional ways, I decided to build on that by developing an interview series. Comfort Classics (which is still going strong, a year later) is a series of over 150 short email interviews with academics, teachers, broadcasters, novelists, artists and students, all talking about something from the ancient world that brings them comfort when times are tough. It’s been my way of generating a sense of community without putting people under any kind of social pressure – but judging by the lovely feedback I’ve received, and over 100,000 views so far, it’s been helpful to people in other ways too.

What was it like teaching in a primary and secondary school? Were there any challenges you may have had to overcome?

I taught in primary and secondary schools all through my postgraduate studies at Newcastle, and for about four or five years afterwards, as a teacher of after-school clubs, a supply teacher or a temporary teacher covering maternity leave. It wasn’t a comfortable environment for me. As I said before, I’m a creature of habit; it takes me a while to adjust to new routines, new places and new people. Jumping in and out of schools as I did, I never had the chance to adjust properly, so school teaching was one long blur of panic for me!

I really struggled with the world of school teaching, and I particularly struggled with the need to deal with other adults in the staff room; but working with the kids was a joy. My favourite school job was a three-month job cover as a Classics teacher in a primary school. There was a rather dull syllabus I was encouraged to follow; but after a while I ditched it and spent the rest of my time there telling stories from myth, and encouraging the children to weave their own characters in and out of the mythic narratives.

That was a wonderful experience, and it reawakened my love of myth, which I’d suppressed for a long time so that I could focus on more mainstream academic interests (my PhD was quite language-intensive). It reminded me how important storytelling is to teaching, at all levels. I don’t think I’d be the teacher I am today if I hadn’t had those few months of telling stories of gods and monsters to wide-eyed children.

Teaching myth to children also helped me in another way. To me, growing up, myth and fantasy had been a shield against the world; they kept me safe and isolated within my own little imaginary bubble. What I found when I started to tell stories was that myth could also be a way of reaching out and connecting with others, through shared experiences and understandings, and through the joint construction of an imagined world. I know that’s an obvious truism: of course stories are supposed to be told! But it was the first time I’d experienced myth as a connecting rather than an isolating force, and as an autistic person who often struggles to connect to people, that was a very powerful realisation. It’s also one of the reasons why I’m so fascinated by the Our Mythical Childhood project; I see such potential in the use of myth as a means of empowering autistic children to reach outward as well as inward.

Thanks for your time Cora Beth it’s been a pleasure!