Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Wiktor Gomulicki, Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka, z 6 rysunkami K. Gorskiego. Warszawa: Gebethner i Wolff, 1905.

ISBN

Available Onllne

literat.ug.edu.pl (accessed: August 1, 2018)

Polona.pl (accessed: March 24, 2022)

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

Historical fiction

Novels

School story*

Target Audience

Crossover (Children and Young Adults)

Cover

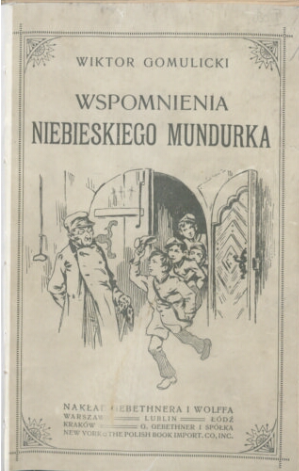

Cover of the second edition from 1913. Available at Polona. Public domain.

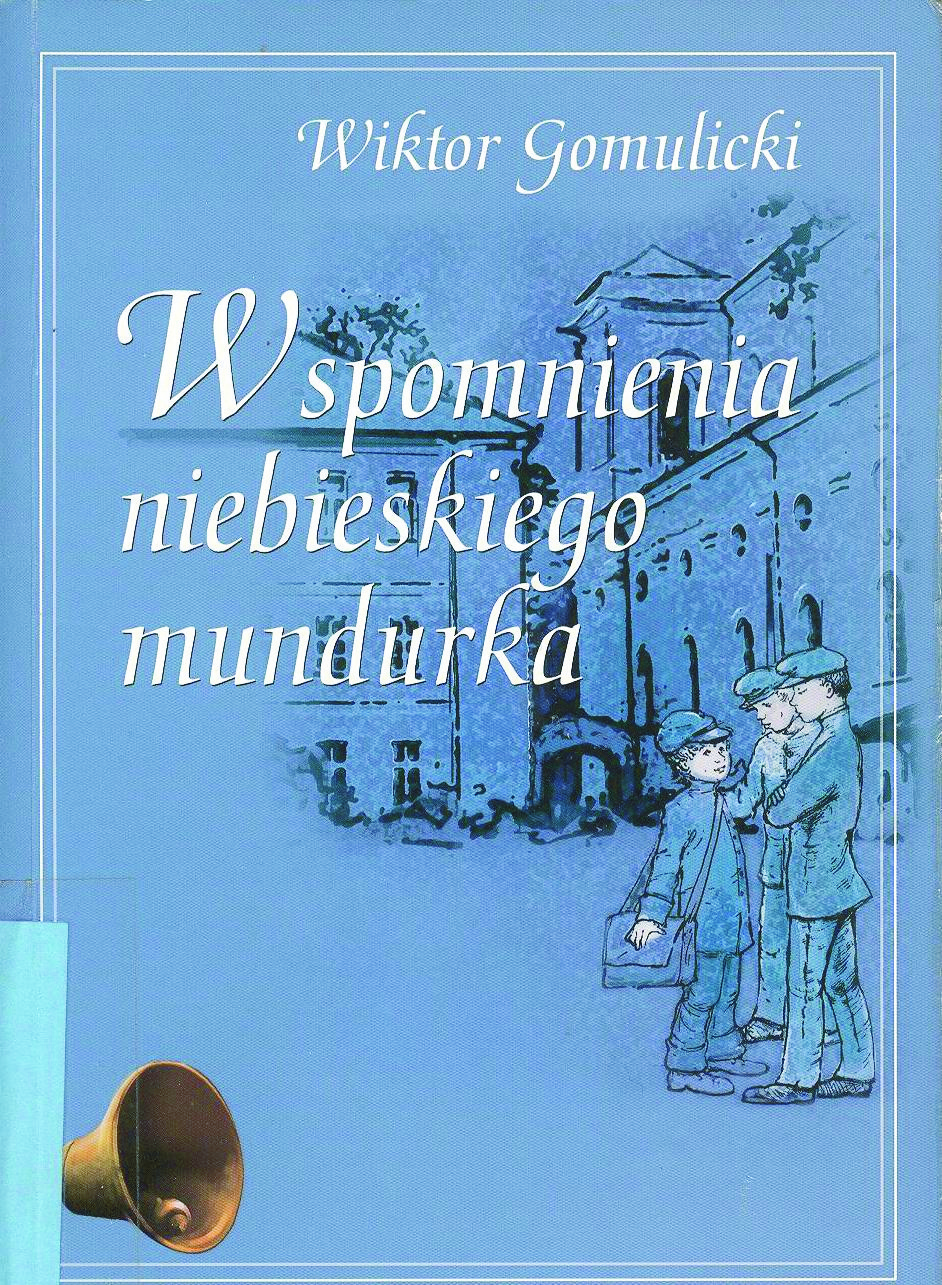

Cover of edition: Wiktor Gomulicki, Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka. Pułtusk, Akademia Humanistyczna im. Aleksandra Gieysztora, 2007.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Karolina Kolinek, University of Warsaw, karolinakolinek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Karolina Anna Kulpa, University of Warsaw, k.kulpa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Wiktor Gomulicki, under creative commons license (accessed: July 2, 2018).

Wiktor Gomulicki

, 1848 - 1919

(Author)

A poet and novelist. Born in Ostrołęka, he attended primary school in Pułtusk. In 1864 he moved to Warsaw, where he went to secondary school and then studied law at the Main School. He abandoned his studies after the Main School was transformed into the Russian Imperial University (1869). He published in several Polish periodicals such as Kurier Warszawski, Kurier Codzienny, Tygodnik Powszechny, Mucha, and Kolce. He authored contemporary novels (e.g. Ciury [Camp Followers], 1907) and historical novels (e.g. Obrazki starowarszawskie [Pictures from Old Warsaw], 1900–1909), as well as short stories and poems highly appreciated by his contemporaries, including the famous Polish poet Julian Tuwim. Gomulicki also translated foreign poetry and took the lead in translating Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal into Polish. He is buried at the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw.

Bio prepared by Karolina Kolinek, University of Warsaw, karolinakolinek@student.uw.edu.pl

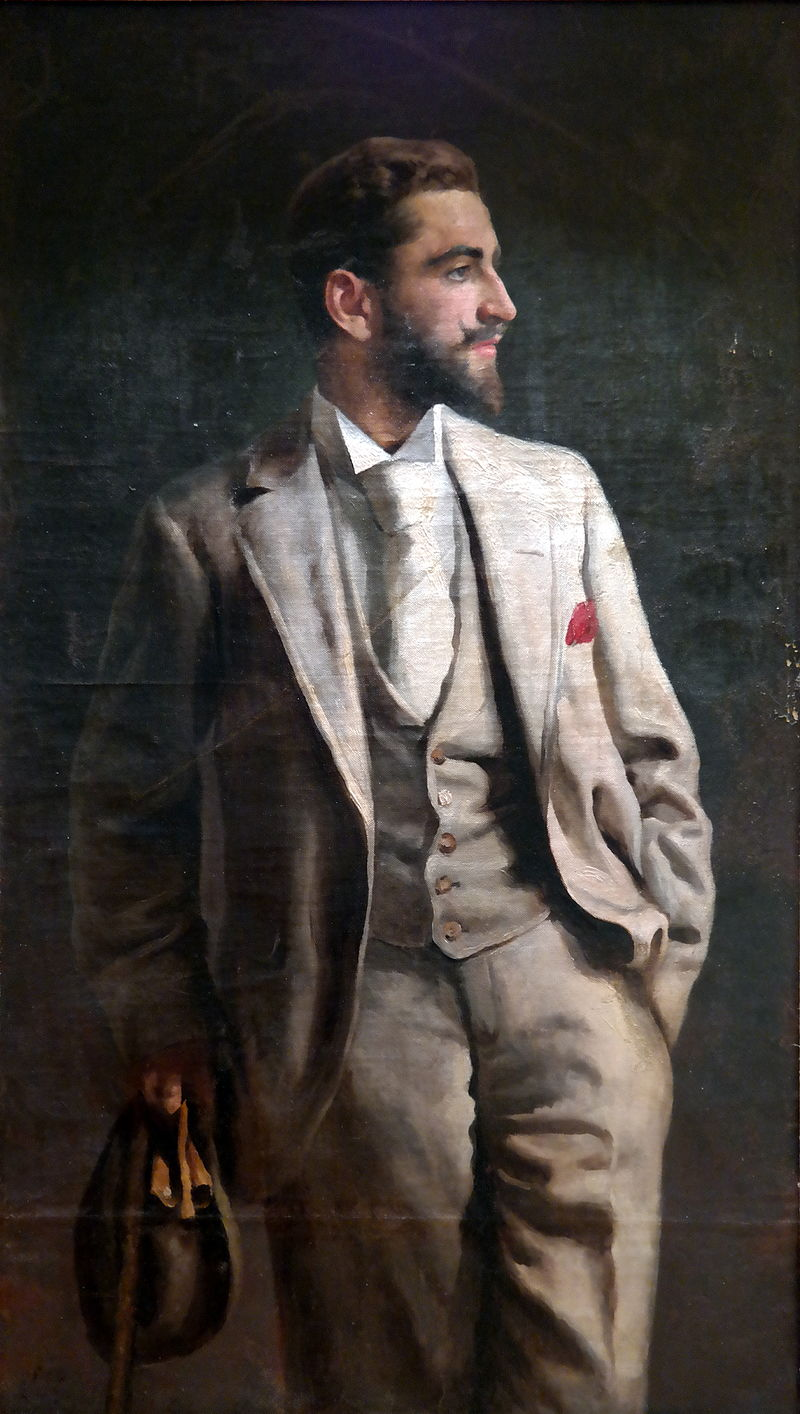

Konstanty Gorski self-portrait, 1896. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 (accessed: April 12, 2022). Virginijus Vizbaras own work.

Konstanty Gorski (Górski)

, 1868 - 1934

(Illustrator)

Konstanty Gorski (also mispronounced as Górski) (1868–1934) was a painter and an illustrator. He was the youngest son of the owner of an estate in Kazimirów [Kazimierzów] (Kazimierava, Kaunas county in today’s Lithuania). He studied fine arts under Ivan Trutniev at a Vilnius school of drawing, later in Moscow, where he graduated from the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture (Московское училище живописи, ваяния и зодчества, МУЖВЗ) in 1887. He then enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts (Императорская Академия художеств) in Saint Petersburg and studied under the direction of a battle painter Bogdan (Gottfried) P. Willewalde. Twice awarded for his works (e. g., gold medal in 1890 for his Male Nude), he continued his studies in Munich, Paris and Rome. From 1895, he lived in Warsaw where he was active in artistic life as a board member of the Warsaw Artistic Society (Warszawskie Towarzystwo Artystyczne). He took part in many exhibitions – in Poland and abroad, including the World’s Fair in Paris in 1900. His works were often reproduced on postcards. He drew for weeklies Wędrowiec [Wanderer], Tygodnik ilustrowany [Illustrated Weekly], Tygodnik polski [Polish Weekly] and Biesiada literacka [Literary Revel]. He was a very popular illustrator of books for adults as well as for children. He cooperated mostly with the Gebethner and Wolff editorial house, illustrating works by famous Polish authors such as, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Juliusz Słowacki, Adam Mickiewicz, Eliza Orzeszkowa, Maria Konopnicka, Maria Rodziewiczówna or Władysław Sieroszewski. His paintings and drawings are held by many museums and galleries in Poland and Lithuania.

Source:

desa.pl (accessed: April 13, 2022).

sztuka.agraart.pl (accessed: April 13, 2022).

Wikipedia (accessed: April 13, 2022).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Pułtusk, a small Polish town, not far from Warsaw (part of the Polish territory under Russian rule), 1859–1864. The plot is based on autobiographical facts from the author’s school years. The main character – Witold Sprężycki, porte-parole of the author, attends a local state school where classes are overcrowded and corporal punishment is commonplace. Each chapter describes another adventure or aspect of the students’ relationship with the teachers. They excel in various forms of mischief and use nicknames for classmates and teachers, often inspired by ancient mythology. Witold is also fascinated by 18th-century Polish poetry and dreams about literary studies in Warsaw. While some memories of tragic events related to Witold’s friends persist, the general mood of the novel is idyllic – it shows the mythical, Arcadian aspects of the author’s childhood.

Analysis

The novel was first released when Poland was partitioned by four foreign powers, including the Russian Empire. In the introduction to the novel’s third edition published in 1919, a year after Poland regained sovereignty, the author marked all the changes imposed in the book by Russian censors, particularly in the profile of the Russian language teacher. The story takes place before the January 1863 Uprising. After its failure in 1864, the Russian government began reprisals against Poles who fought in the uprising and intensified the process of forced Russification, including the educational system.* In 1906, when Gomulicki published his novel, he had been unable to portray the Russian language teacher as an alcoholic rejected by his students and colleagues.

The narrator, representing in the novel the point of view of the author, is a father of two, who nostalgically recalls the time spent at the school in Pułtusk under Russian rule, during the decade of 1860–1870.** A piece of his old uniform – a blue collar edged with a silver ribbon - evokes the memories of his friends, teachers and adventures at the local gymnasium. The compulsory school uniforms were introduced by tsar’s law.*** The similarities and differences between those times and today are obvious. The first and obvious difference is that the schools were boys’ schools, which means that all the students and teachers in the Pułtusk school were male. The only women were people who rented rooms to out of town boys. The second is the ethnic diversity in Pułtusk, a multicultural mix of Jews, Poles, and Russians. To highlight these differences, the author uses slang and regional vocabulary and grammar. The third difference is a system of strict discipline at school enforced with the aid of various levels of punishment: caning, pulling of hair, and detention monitored by a severe inspector.

It should be noted that Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka corresponds with the growing popularity of school stories in nineteenth and twentieth century’s literature, particularly in the United Kingdom. Life in male school is described in e.g. David Copperfield by Charles Dickens from 1850, Tom Brown’s School Days by Thomas Hugens from 1857 and Eric, or, Little by Little by Frederic W. Farrar from 1858. In turn adventures of female students, we could find in that kind of novels as e.g. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë from 1847, Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett from 1905, Just Patty by Jean Webster from 1911 and Anne of Windy Poplars by Lucy Maud Montgomery from 1936. The most important difference between Gomulicki’s novel and British texts is the type of school, where the story is settled. Gymnasium in Pułtusk is without boarding house, so half of the students come from town, where they live with their families. The second half resides in rented rooms in few places. So the students don’t spend the whole time together like in British boarding schools. The second difference is the social state of students. In Gomulicki’s text, this state is much diversified from the boy, who is carpenter’s son and have to sleep in a coffin in father’s workshop, because there are no money and place for his bed to well-to-do families like Sprężycki. The social statue does not such matter at school, where all boys wear the same uniforms. We also could note parallels between this Polish novel and British school stories’ literature. First of all the same stereotypical school characters like the most popular boy or girl at school, sometimes also wealthy (e.g. in Gomulicki’s text is Sprężycki, in Dickens’s is Steerforth, in Burnett’s is Sara); an orphan or half-orphan (e.g. Kozłowski in Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka or David Copperfield); student top of the class (like Sprężycki or Steerforth); flatterer (e.g. Ślimacki); newcomer (e.g. Mieszkowski in Gomulicki’s text and George Arthur in Tom Brown’s School Days); “school dunce” (like Kozłowski in Wspomnienia… and Ermengarde in Little Princess) and beefcake (like Kucharzewski). The second similarity is a system of various levels of punishment including caning, detention monitored by a severe inspector. The third one is the problem of bullying, unfortunately still present in contemporary schools. The school stories are still popular in literature and cinema, although like Harry Potter or High School Musical series now they are settled in coeducational schools.

The classical education in gymnasium remains a significant motif in Gomulicki’s text. The Mass, of course, is celebrated in Latin and is of particular interest to boys who want to be priests. The Latin language is also required for other future studies. We attend a Latin lesson**** in chapter eleven entitled Dzień chrabąszczowy [May Beetle’s Day]. Difficulties with Latin grammar learnt by heart by a student called Kucharzewski are described in chapter eight entitled Dawid i Goliat [David and Goliath]. The Latin teacher named Izdebski has a hot temper and some weaknesses, such as drinking wine and using snuff. Teachers of the Polish language are his opposites, the older Skowroński and, after his death, the young Chabrowski are both loved by students. It should be noted that the author has brought out a patriotic aspect of reading Polish literature by students, particularly great Polish poets, Adam Mickiewicz, Ignacy Krasicki and Adam Naruszewicz. The students have respect to Polish lessons and Sprężycki, the main character is deeply touched when he reads Pan Tadeusz [Sir Thaddeus] and Konrad Wallenrod by Adam Mickiewicz. In describing characters, the author uses comparisons with mythological and ancient historical figures, e.g., the Colossus of Rhodes (chapter two), Jupiter Tonans – Thundering Jupiter (chapter three, eleven, twelve, sixteen), Cato the Elder (chapters four and nine), Hephaestus (chapter six), caryatids, Hercules, Pylades and Orestes (chapter eight), Triton (chapter ten), Saturn (chapter twelve), Neron (chapter seventeen).

The book ends with the coming of the “new.” First, the new inspector loves children and changes the school’s rules including corporal punishment. The teachers are nicer to students and become real pedagogues. The boys finish gymnasium and although they embark on different careers, they believe that they start their new life as adult educated men. Only later readers realize that this generation will have to fight and potentially give their life soon, during the January Uprising.

* In 1879 Alexander Apukhtin become superintendent of the so-called Congress Poland (Russian partition) and was responsible for making Russian the language of instruction in Polish schools. See: E. Staszyński, Polityka oświatowa caratu w Królestwie Polskim (od powstania styczniowego do I wojny światowej), Warsaw: Państwowe Zakłady Wydawnictw Szkolnych, 1968; L. Szymański, Zarys polityki caratu wobec szkolnictwa ogólnokształcącego w Królestwie Polskim w latach 1815–1915, Wrocław: AWF, 1983; K. Poznański, ed., Walka caratu ze szkołą polską w Królestwie Polskim w latach 1831–1870 (materiały źródłowe), Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogiki Specjalnej im. Marii Grzegorzewskiej, 1994.

** About the reform of the educational system for Polish youth in Congress Poland (under Russian rule) in mid-nineteenth-century see: K. Poznański, Oświata i szkolnictwo w Królestwie Polskim 1831–1869. Lata zmagań i nadziei. Polityka oświatowa caratu w latach 1834–1861, Warsaw: Akademia Pedagogiki Specjalnej im. Marii Grzegorzewskiej, 2004, 74–144.

*** Ibidem, 126.

**** Latin was a compulsory subject in the gymnasium. The students had four class periods during the first, second and fourth year, five periods during the third and sixth year and six periods in their fifth and seventh year, see ibidem, 115.

Further Reading

Burdziej, Bogdan and Andrzej Stoff, eds., Wiktor Gomulicki znany i nieznany, Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2012.

Gomulicki, Juliusz Wiktor, "Wspomnienia czułego serca", in Wiktor Gomulicki, Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka, Pułtusk: Akademia Humanistyczna im. Aleksandra Gieysztora, 2007, 323–345.

Nowoszewski, Roman and Juliusz Wiktor Gomulicki, eds., Poeta i jego świat. Bibliografia wszystkich osobno wydanych dzieł Wiktora Gomulickiego 1868–1998, Warszawa: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Książki, 1998.

Addenda

Entry based on: Wiktor Gomulicki, Wspomnienia niebieskiego mundurka. Pułtusk: Akademia Humanistyczna im. Aleksandra Gieysztora, 2007, 346 pp.