Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Renée Grimaud, Les Colonnes d’Hercule. Atlas de la mythologie grecque. Paris: Hatier, 1992, 134 n.p. (152) pp.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Demo of 15 % pages available at Gallica.bnf.fr

Genre

Album

Anthology of myths*

Children's atlases

Children's maps

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Courtesy of Daniel Maja.

Author of the Entry:

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Renée Grimaud (Grimaud Ayanoglou)

, 1929 - 2020

(Author)

Renée Grimaud was a French historian, professor at the IREST (Institut de recherche et d'études supérieures du tourisme), passionately interested in history, art history, classical literature and archaeology. She authored many tourist guides (Paris, Havre, Normandy, Dordogne and Southwest France, Italy, Venice, Naples, Greece, Greek Islands, Athens, Spain) and cultural guides (Sisley, Pissarro, Renoir, Ingres, Delacroix, Degas, Corot, Manet), historical and archaeological books, published by Editions Larousse Hachette, Le Chêne, Parigramme, Hatier. Her tourist guides were translated into English, Italian, Dutch and German.

Her publications cover many periods from French history, including Gaul and Roman Gaul (Nos ancêtres les Gaulois, La civilisation gauloise), the history of Paris, the Napoleonic era or so-called “small history” (Petites histoires des grands châteaux, Le chat de Louis XV et autres animaux choyés de l’Histoire, La Roseraie de Joséphine et autres jardins merveilleux de l’Histoire, La fabuleuse histoire des nuits parisiennes). She also wrote books aimed at children which popularize Greek mythology and language: Les Colonnes d’Hercule. Atlas de la mythologie grecque and Alphabêta. L'alphabet grec par ses legends, illustrated by Daniel Maja.

Source:

Renée Grimaud biography at Babelio website (accessed: October 15, 2021).

Renée Grimaud s’en est allée at Midi Libre website (accessed: October 15, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Courtesy of Daniel Maja.

Daniel Maja

, b. 1942

(Illustrator)

Daniel Maja (born 1942 in Paris) graduated from l’École Estienne in Paris (former l’École supérieure des arts et industries graphiques ESAIG), a press illustrator, a cartoonist, an illustrator of many books for children and for adults, and teacher of drawing at École Émile-Cohl. He collaborated with many newspapers and magazines, both French (Le Monde, Le Figaro, Le Magazine Littéraire, Lire, Votre Beauté, Beaux-Arts, Télérama, J’aime Lire and others) and foreign (The New-Yorker). He illustrated well known books by such authors as Erich Kästner, Astrid Lindgren or Jean de La Fontaine, often published in editorial series aimed at young readers, like Le livre de poche jeunesse by Hachette, Arc en poche by Nathan or Folio Junior by Gallimard Jeunesse. Since 2008 he posts a daily drawing « la vie brève » on his website danielmaja.com

Source:

Official website biographie (accessed: October 15, 2021),

Wikipedia.fr (accessed: October 15, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

The publication is addressed to a young audience. It is an atlas focusing on ancient and mythological sites in the Mediterranean Basin associated with Greek civilization. The atlas contains maps of ancient locations and complete descriptions of places related to mythological stories and characters.

Grimaud divides the book into seven chapters, including maps by Catherine Zacharopoulou and illustrations by Daniel Maja. There is also a Glossary and an Index of geographical names.

The maps cover Greece with its regions and ancient sites, capes, straits, islands, lakes, seas and springs, rivers and mountains, the world of Greek mythology, the grand journeys of Jason, Perseus, Ulysses and Heracles, the constellations, Seven Wonders of the ancient world. On the maps, there are only the regions and sites mentioned in the text. Modern names are indicated in parentheses.

Illustrations courtesy of Daniel Maja

Analysis

Greek mythology includes a lot of geographical names not always well known from contemporary geography. The atlas places mythological names in their ancient location, even though some of them are difficult, even today, to identify precisely (e.g., the Simoeis river whose course has changed), some never existed in reality (e.g., Tartarus) or disappeared (e.g., the Copais lake in Boeotia which was drained). In addition, Grimaud provides answers to questions often asked by children when they listen to the stories, like where? Where was Nemea? Where did the Hydra live? What does Erymanthian or Stymphalian mean – all these questions are answered in Grimaud’s book. Thus the atlas not only satisfies readers’ curiosity but is also a great tool in learning more about Greek mythology through a useful blend of colourful visualizations, mythological stories and additional explanations.

The book combines a dictionary of mythology with entries in alphabetical order, an atlas with maps, retellings of myths, legends and fun facts, and references to ancient literature and contemporary literary culture. Myths are retold, not in a chronological order starting with chaos and the beginnings of the world nor by stories about particular gods, heroes. The geographical location serves as a reference point; each place is described along with mythical stories connected to it (see below). For example, when describing Argolis, the entire region is mentioned and its cities, each with its sub-chapter: Argos, Corinth, Epidaurus, Mycenae, Nemea, Sicyon and Troezen. Each description refers to the geographical location, the origins and legendary history, myths and characters connected with each city.

Ancient figures are not the only ones mentioned. For instance, Jean Racine used ancient archetypes in his dramatic works, Albert Camus wrote his famous essay Le Mythe de Sisyphe*, and Heinrich Schliemann conducted archaeological excavations at Mycenae. The author directly refers to ancient literature and quotes from great authors, like Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides (see below) or Pindar, to add authenticity to the myths. At the same time, she familiarizes the child reader with the reception of ancient myths and literature in the culture of subsequent generations, including mythological references, collocations and idioms present in the contemporary language.

The lands known solely from mythology are also presented. The ancient sources describe them in detail, and their themes are still present in today’s culture. For instance, the author presents Atlantis, Cimmeria or Tartarus as universally known mythological places.

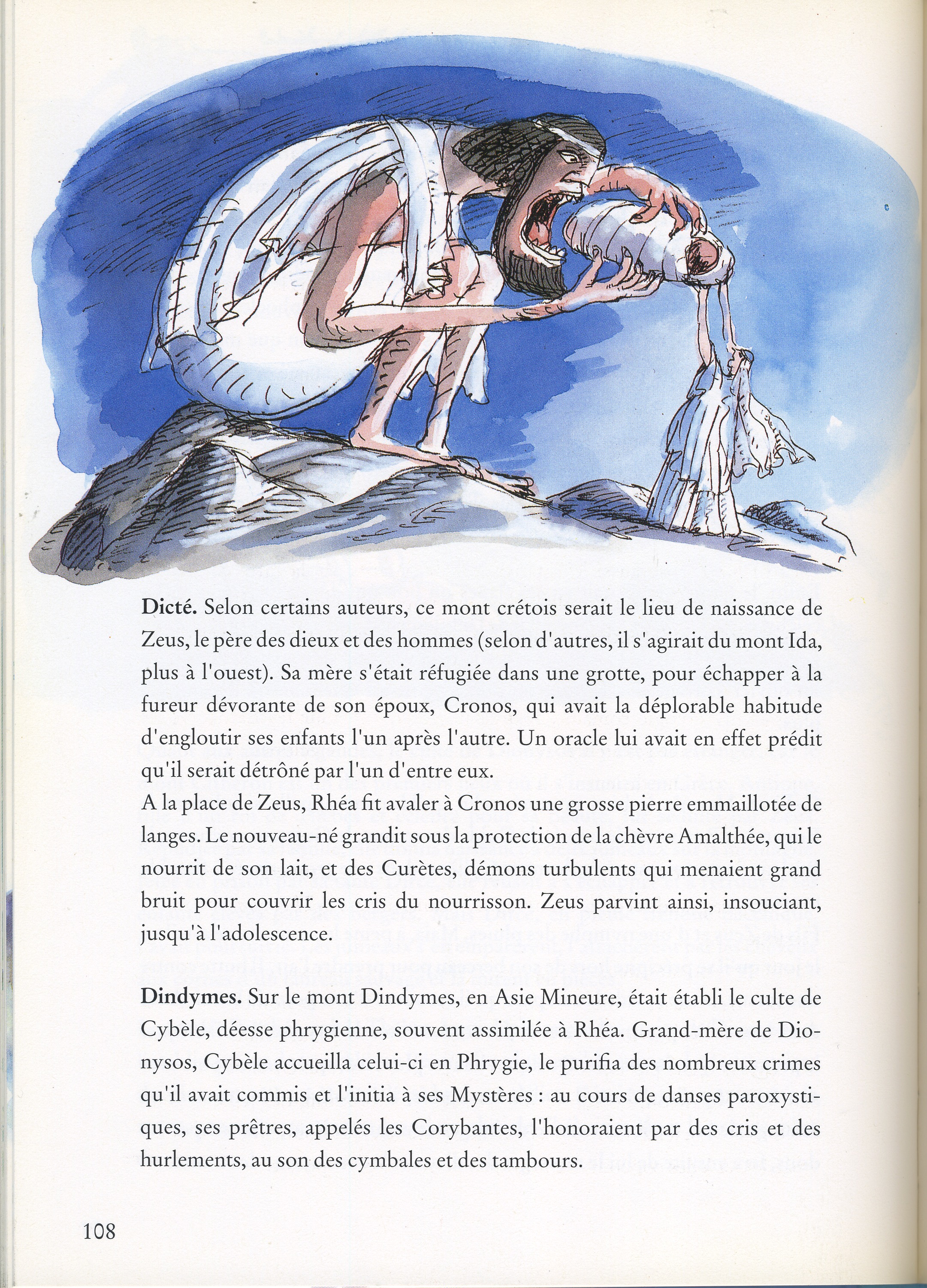

Besides the educational and entertaining value of the maps and the text, the illustrations by Daniel Maja are an undeniable asset: they draw children’s attention. The cover presents Heracles wearing the lion’s hide. He establishes the title pillars by separating two mountains. His feet rest on the rocks, resembling the pose which the Ceutan artist Ginés Serrán Pagán used later, in 2007, designing the statue of Heracles in Ceuta. All the illustrations maintain a light pastel tonality and include as many mythological and cultural elements as possible, with direct reference to the book’s text. For example, the picture of Arcas hunting the she-bear, who is his mother Callisto, shows precisely the moment in the story when Arcas is about to pierce the big animal with his spear. The spear is held by the hand of Zeus to prevent the boy from committing matricide.

The picture of Theseus picking up the rock covering his father’s sword underlines his supernatural strength by showing the size of the rock – a massive piece of land on which grow big trees. The large illustrations, referring to the whole region or chapter and not to a particular myth, are filled with many creatures, characters, statues of gods, buildings and/or other recognizable features discussed in the chapter.

* Camus, Albert, Le mythe de Sisyphe: essai sur l'absurde, Paris: Gallimard, 1942.

Further Reading

Camus, Albert, Le mythe de Sisyphe: essai sur l’absurde, Paris: Gallimard, 1942.

Grimaud, Renée, Alphabêta. L’alphabet grec par ses légendes, Paris: Seuil, 1995.

Grimaud, Renée, Sous nos pas, Gaule, Paris: Hatier, 1993.

Murnaghan, Sheila, “Classics for Cool Kids: Popular and Unpopular Versions of Antiquity for Children”, The Classical World 104.3 (2011): 339–353.

Racine, Jean Baptiste, Oeuvres complètes. Tome I: Théâtre – Poésie, Georges Forestier, ed., Gallimard, 1999.

Addenda

Illustrations courtesy of Daniel Maja