Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

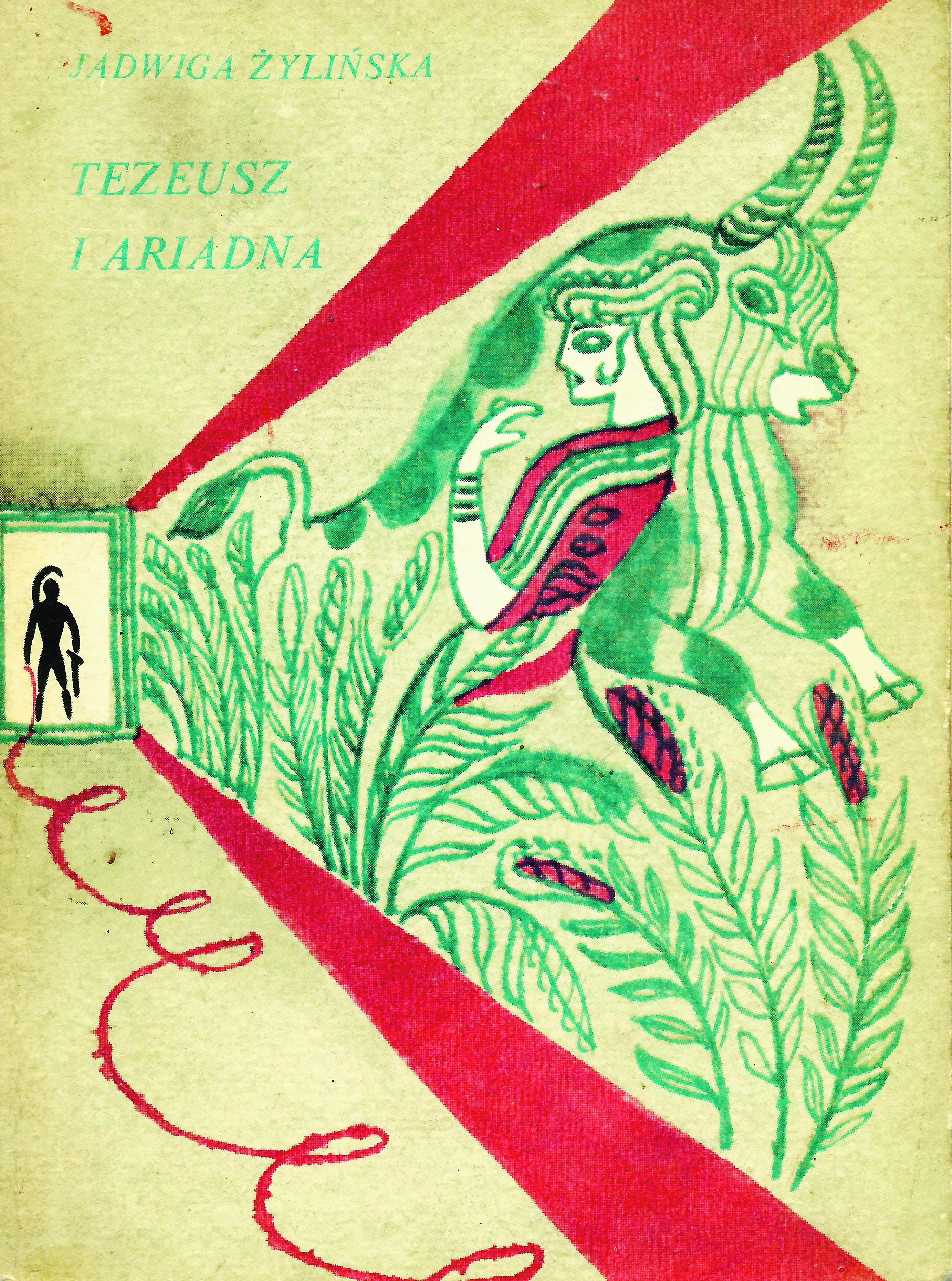

Jadwiga Żylińska, Tezeusz i Ariadna. Warszawa: Biuro Wydawniczo-Propagandowe RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch”, 1973, 58 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The publisher of the text closed down in 1990 leaving no known successors, and we were unable to determine if there are any copyright holders. Including the cover in our database meets all fair use requirements, still, we invite the users to share with us any information they may have about copyrights to the posted materials.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Ilona Szewczyk, University of Warsaw, szewczyk@obta.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

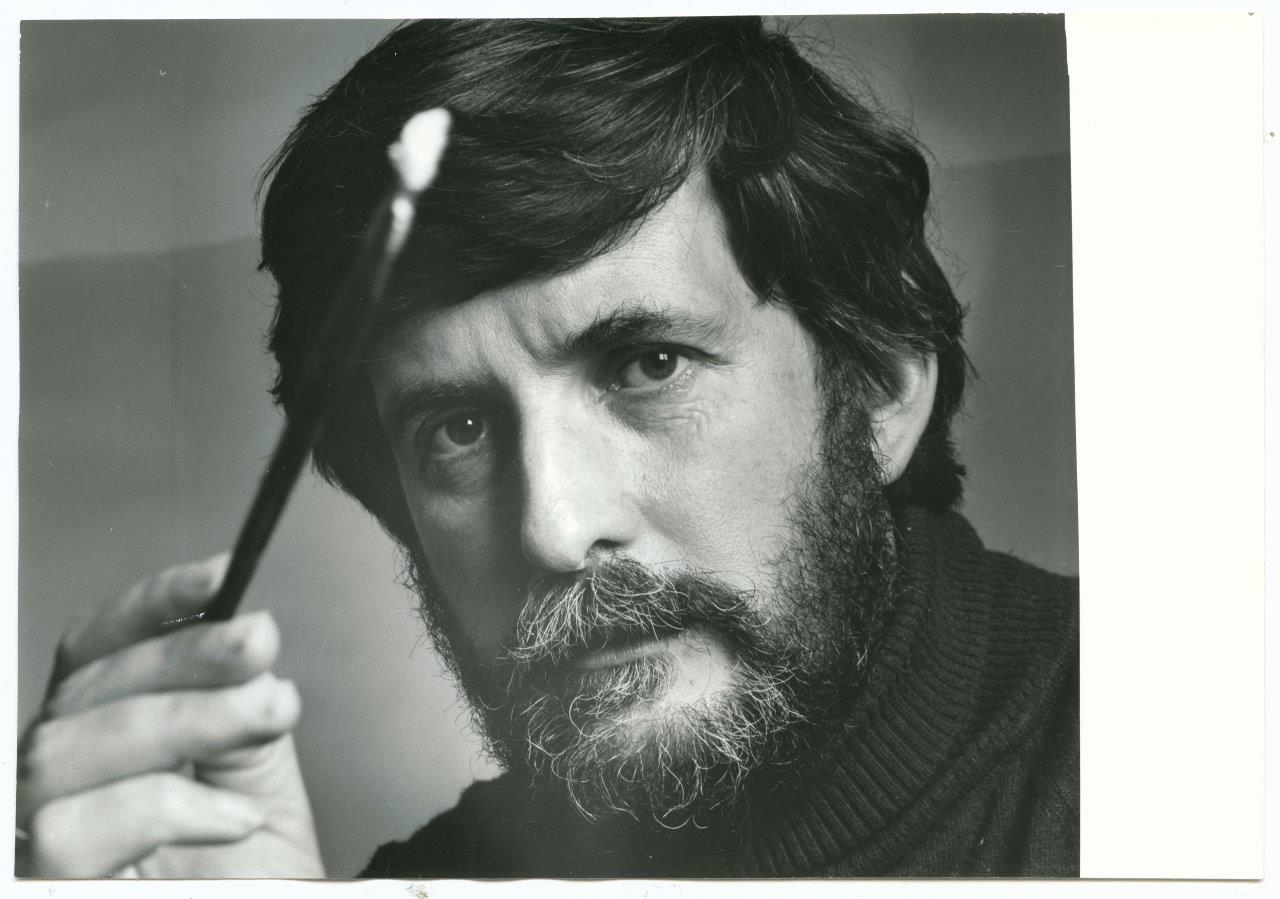

Courtesy of Barbara Towpik-Roszkiewicz, daughter of the artist.

Janusz Towpik

, 1934 - 1981

(Illustrator)

Janusz Towpik (1934–1981), originally from Cieszyn, was an architect with a diploma from the Warsaw University of Technology [Politechnika Warszawska] (1959). He also studied graphic design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw [Akademia Sztuk Pięknych] and became a graphic designer and an illustrator. He designed postcards, stamps, matchbox labels, ex libris, logotypes, tapestries and intarsias.

Towpik illustrated children’s books, textbooks, fairy tales, and other stories to be viewed with a projector, nature atlases, popular science books, especially those about animals, and produced zoological tables for the PWN Encyclopaedia. In addition, he taught drawing at the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology and conducted an arts club for children at the Warsaw Zoo.

Selected publications illustrated by Janusz Towpik, examples of his works, awards and exhibitions can be viewed online here and here (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Sources:

janusztowpik.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik", at Artinfo.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik. Natura i Fantazja", at ownetic.com (accessed: September 9, 2021),

"Janusz Towpik – Czarodziej Natury", at muzeum.edu.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Gieżyński, Stanisław, Zwierzęta małe i duże, at Weranda.pl (accessed: September 9, 2021),

Towpik-Roszkiewicz, Barbara, Janusz Towpik, at Legendy Polskiego Jeździectwa website (accessed: September 9, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

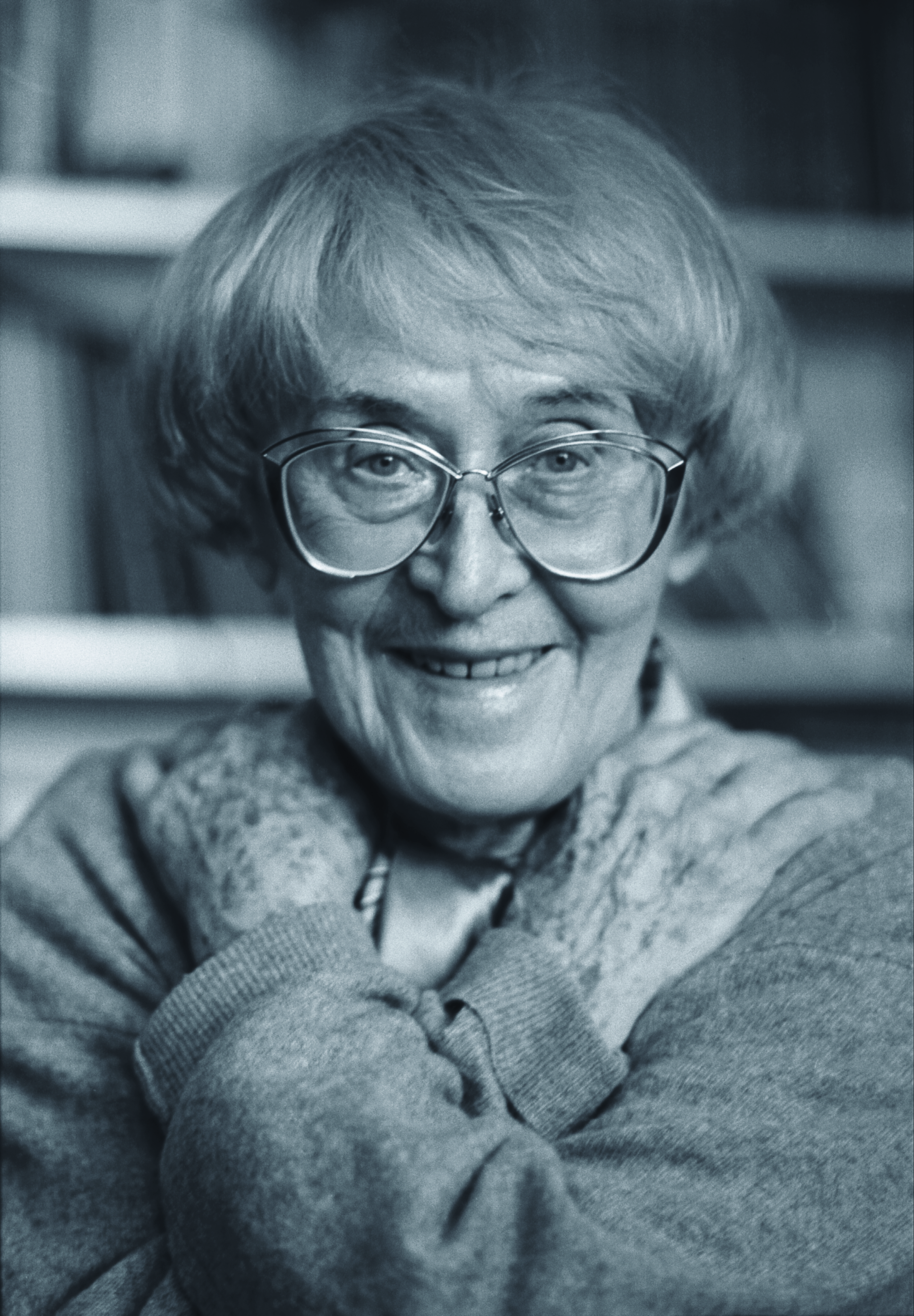

Photograph courtesy of its Author, Elżbieta Lempp.

Jadwiga Żylińska

, 1910 - 2009

(Author)

Born in Wrocław, lived in southern Wielkopolska [Greater Poland] (Ostrzeszów and Ostrów Wielkopolski), which influenced her later life. Graduated in English philology from the University of Poznań. Proficient in Latin, ancient Greek, English, and French. For many years worked for the Polish Radio. Prose writer, essayist, author of screenplays, radio dramas, historical novels, and books for children and young readers. Well known as an author of historical novels written from a woman’s point of view (the most important among these is a 2-volume novel Złota włócznia [The Golden Spear], 1961–1964). She made her debut in 1931 with a story for children Królewicz grajek [The Prince Piper] published in a periodical (still under her maiden name Michalska). Since 1964 member of the Polish PEN Club, in 1993 received the Polish PEN Club prize for lifetime achievement as a prose writer. Decorated with the Knight’s Cross of Polonia Restituta for outstanding achievements for Polish culture. Some of her books were translated into German and Russian. She is the author of a cycle Oto minojska baśń Krety [Here is the Minoan Tale of Crete], 1986, parts of which were also published separately.

Source:

Żylińska Jadwiga, in: Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, eds., Wspołcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 10: Ż, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2007, pp. 66–69.

Bio prepared by Gabriela Rogowska, University of Warsaw, g.rogowska@al.uw.edu.pl

Translation

Russian: Тесей и Ариадна [Tesej i Ariadna], trans. Ewa Wasilewska, Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza RSW „Prasa–Książka–Ruch”, 1977.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Every nine years, Athenians must send seven boys and girls to Crete as a tribute for the Minotaur, half-bull, half-human. The young prince, Theseus, decides to travel with the young people chosen for the sacrifice and kill the monster. When he arrives at the royal palace, he acquires an unexpected ally: Ariadne, the queen of Crete, who asks him to meet her in the sacred wood at night; there, she gives him a ball of red wool. Using this thread, he finds his way back from the Labyrinth. Theseus manages to kill the Minotaur, who turns out to be Taurus, the leader of Ariadne’s palace guards. After his victory, the hero commits a sacrilege by capturing Ariadne. He intends to take her to Athens with him. Unfortunately, a sudden storm prevents the Athenians from continuing their journey. Convinced that the storm was a punishment from the gods for kidnapping the Cretan queen, Theseus leaves her on the island of Naxos. Dionysus and his merry companions wake up the girl. When she learns that her sister Phaedra has taken over power on Crete, Ariadne accepts Dionysus' proposal to stay with him on the paradise island of Naxos.

Analysis

Żylińska presents, to the child reader, her interpretation of the Cretan myth. She contrasts the two different worlds – Athens and Crete – declaring priority of the latter. First of all, Athenians are responsible for the treacherous death of the Cretan prince during the sacred truce, which can be considered barbarous. Later, the reader is introduced to the Knossos palace, where the Athenian heir, amazed by its beauty and sophistication, is also presented as a petitioner (p. 17) and a barbarian (p. 21). He feels out of place, like "an uncouth shepherd who miraculously reached the abode of gods’ residence" (p. 19), and, impressed by the Cretan capital, is merely an ordinary provincial in a big city (p. 21, p. 40). The final unfavourable difference between the two civilizations is their attitude towards other people and cultures. Although Ariadne’s father demanded a tribute of Athenian youths as the price for his son’s life, the queen reveals that all the hostages take part in the games as contestants, then are liberated, and out of admiration for the Cretan culture and lifestyle, they eventually chose to stay there rather than return home. On the other hand, Theseus shows himself to be a coarse barbarian, when after being rejected by Ariadne, he is incapable of respecting her decision and abducts her against her will, violating the rules of conduct. The differences between Crete and continental Greece are highlighted by the brilliant illustrations of Janusz Towpik, who drew the Cretan characters in a manner resembling Minoan art while portraying Theseus like a stylized 5th-century hoplite in a Corinthian helmet.

Although Theseus is presented as a “cousin from the country”, he remains a hero. His lack of sophistication does not detract from his achievements. The hero embarks on a journey and undertakes an extremely dangerous task to serve his community and prove himself as a man, a warrior and a future leader. His lonely road through the Labyrinth requires intelligence, persistence, courage and physical force. That is why Ariadne calls his deed worthy of a true hero. Unfortunately, despite defeating the Minotaur, freeing Attica from the tribute and becoming a hero, he is unable to live happily ever after because he yearns for the charm of Crete.

The author introduced elements of “feminist theology” or “Goddess movement”, popular in the 1970s when the book was written. The role of women in the Cretan society is strongly emphasized. It is not Minos, the sovereign of the state who receives the Athenians, but the Queen and Nymph of Crete. Ariadne is presented as a smart and prudent politician raised by a high priestess to become the ruler since her childhood. The important duties she fulfills in society prevent her from bridging the differences between her and Theseus. It is unthinkable for her to consider elopement – the Nymph of Crete cannot leave her island. After the abduction, Phaedra is acclaimed as the next female ruler. The influence of feminist theology can also be seen in the introduction of the character of Dionysus. His origin is mentioned three times, and each time he is called the son of the Theban princess Semele, nothing is said about his father as if he never had a male ancestor.

An interesting narrative strategy is the use of a literary device called a story within a story for introducing the character of Dionysus. Following rather the character of Ariadne than of Theseus, the reader learns about her fate on Naxos: standing side by side with Dionysus, she is the new co-ruler of the island.

The illustrations form a coherent part of the book. Towpik, from the very beginning, uses brilliant minimalistic and suggestive ink and colour compositions that highlight, simply, the most important details, leaving room for one’s imagination and interpretation.

Further Reading

Fiałkowski, Tomasz, "Łańcuch dziejów, łańcuch życia: Jadwiga Żylińska”, Tygodnik Powszechny. Katolickie pismo społeczno-kulturalne 21 (2009) . Online: https://www.tygodnikpowszechny.pl/lancuch-dziejow-lancuch-zycia-136557

Kraskowska, Ewa, "Her Story w twórczości Jadwigi Żylińskiej”, FA-art. Kwartalnik Ruchu „Wolność i Pokój” 3 (2009): 26–33.

Marzec, Lucyna, Po kądzieli. Feministyczne pisarstwo Jadwigi Żylińskiej, Poznań: Wydawnictwo Nauka i Innowacje, 2014.

Sucharski, Robert A., “Jadwiga Żylińska’s Fabulous Antiquity”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Childhood... The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Boston–Leiden: Brill, 2016, 120–126.