Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Yan Marchand, Socrate sort de l’ombre. Paris: Les Petits Platons, 2012, 64 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

The book’s page on the official website of the publishing house (Accessed: November 26, 2021).

Available Onllne

Available for purchase on the official website of the publishing house (Accessed: November 26, 2021).

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Adaptations

Fiction

Illustrated works

Philosophical fiction

Short stories

Target Audience

Crossover

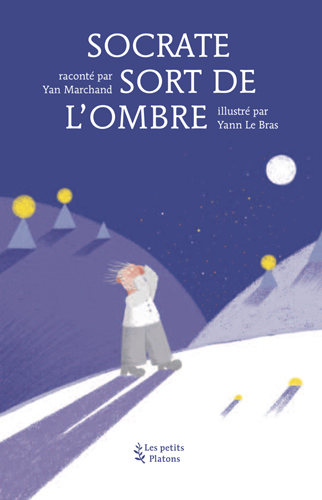

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Angelina Gerus, University of Warsaw, angelina.gerus@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Yann Le Bras (Illustrator)

Yann Le Bras is an illustrator based in Strasbourg, France. He studied visual arts at Rennes II University. He now works as an illustrator with the educational department of the Tomi Ungerer Museum. The first book illustrated by Yann Le Bras was La Mort du Divin Socrate (The Death of Divine Socrates, 2010). Among his later works are Le roi Midas et ses oreilles d’âne (Midas the King and His Donkey Ears, 2012), Socrate sort de l’Ombre (Socrates steps out of the Shadow, 2012), and Socrate Président ! (Socrates the President !, 2017).

Source:

Official website (accessed: December 2, 2021).

lespetitsplatons.com (accessed: December 2, 2021).

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk and Angelina Gerus, University of Warsaw, angelina.gerus@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Yan Marchand

, b. 1978

(Author)

Yan Marchand, born in 1978, is a writer of books for young adults, based in Brest. Holding a PhD in philosophy from the Université de Rennes 1, he offers philosophy workshops for children and teenagers from 5 up to 17 years. He also runs trainings and lectures for teachers and childcare professionals wishing to incorporate philosophy into their practices. In cooperation with the Paris-based publishing house, “Les petits Platons”, Yan Marchand authored several children's books including Diogène l’homme chien (Diogenes the Dog-Man, 2011), Le rire d’Épicure (The Laughter of Epicurus, 2012), Socrate sort de l’ombre (Socrates Comes out of the Shadows, 2012), La révolte d’Épictète (The Revolt of Epictetus, 2014), Les mystères d'Héraclite (The Mysteries of Heraclitus, 2015), Socrate président ! (Socrates the President !, 2017).

Sources:

Personal webpage (Accessed: October 13, 2021).

lespetitsplatons.com (Accessed: October 13, 2021).

catalogue.bnf.fr (Accessed: October 13, 2021).

idref.fr (Accessed: October 13, 2021).

Bio prepared by Angelina Gerus, University of Warsaw, angelina.gerus@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to working with Greek and Roman philosophy?

— The encounter with Antiquity occurred, as it does for many children, through mythology. Digging to the right, to the left I ran into a book of Sophocles. It fascinated me, and, mixing up pretty much everything at the time, I put all the Ancients in the same basket; so I began to read Aeschylus, Horace, but also Seneca, Lucretius, Epictetus, Plato, not knowing yet that it was philosophy. And that captivated me: finally, books that did not tell stories but proposed ways of living in connection with a better understanding of the world and our finitude.

2. As you have a background in philosophical education holding a PhD in philosophy from the Université de Rennes 1, may you point out any particular books that made an impact on your writings?

— My writings interact with Heraclitus, the pre-Socratics in general and the philosophies of asceticism: cynicism, epicureanism, stoicism mainly. It's hard to point out any books. But more recent authors have influenced my writing, I believe. Heidegger and Levinas. But unfortunately, I cannot suggest a specific title.

3. I have an impression that in your stories the ancient texts are interwoven so closely with new authorial elements that it is sometimes difficult to separate them from each other. What sources are you using? How concerned are you with ‘accuracy’ or ‘fidelity’ to the original?

— There is always the lie of art! Indeed, in writing for the youth there are two often incompatible issues: the exposition of an often complex thought, and the proposal of a motivating narration. Sometimes it is necessary to adjust either the narrative or the exposition of concepts, so that there may arise some inventions which serve the story rather than the history of philosophy, and moments when the story weighs a bit more as it becomes more philosophical. But as far as possible, I create a plausible framework. I work on the biography, the historical and psychological context of the epoch and I try to see in what way the concepts of this or that author could make sense at that time, in that particular context. This gives ideas for plot twists. Therefore I try to be faithful to the century and to the spirit of the philosopher, but sometimes in order to give a bit of energy I can modify a fact without ever inventing it from scratch. It's a bit like a puzzle with a missing piece: I cut a new one but to make it fit, I have to tap on it with a fist.

4. What challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular texts or ideas?

— The challenges are often the same: to open a complex world to a reader without boring him. I therefore choose authors who often have a life on which I can base my concepts and who provide images, models and amusing examples that I steal without remorse. The other challenge concerns the length: it is not possible to produce a thousand pages, and yet our author has said many things. It is therefore necessary to reread everything and to make an important summary while remaining silent about other elements. For Heraclitus it is still fine, but for Heidegger it becomes a complex task. And the biggest challenge is this one: on the one hand you want to produce arguments and leave the fiction, or else you get caught up by the fiction and the text becomes weakly philosophical.

5. You have written children's books about different philosophers of Antiquity: who was the hardest and easiest to tell the story about?

— In general, these short books demand a huge amount of time from me. There is something of poetic writing, because it is necessary to contain the author, to write the text ten or twenty times before finding the fulgurance which will hold on a few dozens of pages. All the writings I proposed to “Les Petits Platons” were reworked several times. They were all difficult to write. The one that seemed to me the most obvious to work on was Diogène l’homme chien (Eng. Diogenes the Dog-Man, 2011), because I had been maturing it for a long time, and he’s a very visual philosopher. I really struggled to draft Thalès et le trône de la sagesse (Eng. Thales and the Throne of Wisdom, 2021), because I wanted to talk about Thales but at the same time about the birth of a new way of thinking about things. So there was a greater philosophical intention.

6. Why do you think Сlassics continue to resonate with young audiences?

— The Ancients speak about thought that discovers a way of looking at things, and I believe that this touches on something of childhood, which also awakens to a way of thinking that becomes capable of grasping the relationship that exists between things. Aristotle said that in order to undo a knot, one must understand how it is made. Ancient thought patiently unties knots, it manipulates, it sees the areas of friction, the points of contact, plays at that. Children too, perhaps. I also think that ancient thought is not just a thought, it proposes a life, or rather a powerful feeling of existence. Children often say that these lives are too risky, but at the same time they admire these incarnations of freedom.

7. Would it be a coincidence that the protagonists of your books in the “Les Petits Platons” series are characters coming-of-age? If it is not by chance, why do these situations become the core of the story?

— Pindar said: become who you are. Indeed my characters are in search of who they have to be and often this new life is not far away, but right there, in a decision, an act, a taking of freedom, right now and not tomorrow. I didn't realise this recurrence in my texts, and you are not the first to point it out to me. But isn't philosophy the proposal of another way of living, freer, more lucid. I therefore like to imagine stories in which the minds undergo a kind of metamorphosis; moreover, I think that young readers rather enjoy this dimension, since isn't their task to grow up?

8. Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers, especially in France?

— I don't know in what sense we should consider the word translation. But if we have to pass on an ancient text, there are passages that can attract young readers, especially those stories about freedom, openness, independence; in a word: autarkeia. And for young people who are in search of emancipation this makes sense. However, something also disturbs me in this ancient thought, because I don't want children to be nourished by this very male vision, which explains to a large extent the hypnotic relationship we have with power, with mastery and the negation of those who need to be accompanied. This freedom as a synonym for autonomy is very pronounced in France, so to think about how we got there is also to recast the concept in order to make it more open to the idea of interdependencies. So in my way of presenting the Ancients, I also try not to caricature them, as a great white-bearded sage and autonomous, but to present complex individuals, sometimes uncomfortable with the concepts of their time, which I think they were, most of them having lived through exile and being put to death or to exile.

9. You offer philosophy workshops and also run different philosophical trainings and lectures. Do you turn to Antiquity in this practice? If so, how often does it happen and how are these references particularly useful and valuable to you as part of your educational activities?

— I plunge my roots in Antiquity. I always have an eye in the antique rear-view mirror, whether with children, adults in training or with expert colleagues. I must have been born in the wrong century, but this is certainly a fantasised Antiquity; however, I borrow a lot of techniques and concepts from Greece especially. I watch over friendship in a permanent conversation. I also insist on the gratuity of the exercise and on the thrill of a thought that divides itself to think what it thinks, let's call it a dialogic function. The knowledge of the Ancients is also precious to accompany philosophical conversations, because it offers elements to think about the genesis of concepts, their evolution in history and therefore their mortality, when we often think that the words of our time are immutable mountains, but which for a long time have not meant very much. They are mutations of the past that only require a retrospective glance to make flesh alive again.

10. Do you have a favourite book by an ancient author?

— Hard to say, but I remember the one that, when I was still a child, made me say: I want to become like that: the Handbook of Epictetus.

11. And a favourite ancient philosopher?

— I hesitate between Heraclitus and Diogenes, am I allowed to merge the two persons into one and invent a Dioclitus? Or a Heragenes?

Prepared and translated from French by Angelina Gerus, University of Warsaw, angelina.gerus@gmail.com

Translation

Spanish: Las cien vidas del filósofo Sócrates, trans. Sara Álvarez Pérez, Madrid: Errata Naturae Editores, 2013, 64 pp.

Turkish: Sokrates Karanlıktan Çıkıyor, trans. Akın Terzi, İstanbul: Metis Yayınları, 2014, 64 pp.

German: Sokrates verlässt das Reich der Schatten, trans. Thomas Laugstien, Zurich-Berlin: Diaphanes Verlag, 2016, 64 pp.

Summary

A sacred ship from Delos arrives in Athens on its return from a mission to the Temple of Apollo. While the citizens enjoy the festival of the Delia, an imprisoned Socrates prepares to drink poison hemlock, as required by his sentence. After death, his soul joins a queue of others who prepare to appear before the three judges personifying the three parts of the psyche – a many-headed bronze beast (desires and pleasures), a silver lion (justice) and a golden man (the reason). There Socrates meets an old acquaintance, the sophist Thrasymachus.

As a judgment for their behaviour when they were alive, the philosopher receives one-thousand years of pleasure in heaven and the sophist one-thousand years of suffering in the abyss. When the time comes, they both head to the Goddess of Destiny and her daughters, the Fates, to choose a new fate. But before returning to earth, both Thrasymachus and Socrates break the rules by not drinking the water of oblivion, therefore remembering their previous experiences. In the first rebirth, the sophist repeats his desire for glory, wealth and power, but Socrates, who became a mosquito, stings him at every unjust act. Thus, they have to live through another millennium of retribution.

Then Socrates suggests to Thrasymachus that he can escape another thousand years of torture by choosing the ideal just city for his soul, a place that his friend Plato once told him about. However, the sophist again tries to cheat fate. In the second reincarnation, Socrates is a dog belonging to Homer, with whom they find themselves in Plato’s utopian Kallipolis. When children (together with a musician Damon) enrage the poet by talking about the usefulness of poetry and its necessary correlation to the knowledge of things, Socrates and Homer wind up in a quiet alley where they meet Thrasymachus, this time as an artisan, a member of the class of Producers. From him, they learn some rules of the ideal state, such as the distribution of children into three groups according to 1. the metal which prevails in their soul (bronze, silver or gold), 2. the inability to change the assigned rank or 3. to choose a partner from a different group. The Guardians teach them about extensive education in Kallipolis – the most gifted students master dialectics – an art that allows discerning genuine truth. Thinking that after fifty years of study, a person would be physically unfit, Homer and Thrasymachus decide to capture the queen for ransom. Along with Socrates, the dog, they learn first-hand that the governors of the ideal state are as strong as they are wise: when the kidnapping fails, all three find themselves once again among the souls of the dead.

During another millennium of punishment, Thrasymachus (this time accompanied by Homer) decides to take revenge on Socrates by setting him up for life in a Cave, where the only true element is the shadows on the walls. Socrates succeeds in breaking free from his shackles and escaping from the Cave. However, he discovers that what seemed real to him was engineered by illusionists. Having gradually become accustomed to the light, Socrates decides to free the other inhabitants of the Cave, but they refuse, preferring the shadow to the light. The philosopher’s soul once again lives justly, while the soul of Thrasymachus, a tyrant in this incarnation, is sent after death to Tartarus, the cruelest and darkest part of the Underworld.

Analysis

The subtitle, “d’après La République de Platon”, is placed in brackets on the book's title page but not on the cover. Several fragments of the classical text form the basis of the plot and determine its main characters and idea: the most influential in this regard are the passages on the immortality of the soul (608d–612) and its tripartite structure (588b–e), the myth of Er (614a–621d), and the allegory of the Cave (514a–520a). As the story is driven by the sequence of lives and afterlives of the main characters, it may be understood as an essential, implicit reference to Cephalus’ words: “when a man begins to realize that he is going to die, he is filled with apprehensions and concern about matters that before did not occur to him. The tales that are told of the world below and how the men who have done wrong here must pay the penalty there, though he may have laughed them down hitherto, then begin to torture his soul with the doubt that there may be some truth in them”* (330d–e). The concept of the perfect state in Marchand’s book is rather marginal. Therefore its main theme isn’t society or politics, but justice, which, according to Diogenes Laërtius, also appears in the second title of Plato’s dialogue – Περὶ δικαίου [Peri dikaiou] (On Justice, cf. D. L. III.60).

However, the short story abandons Plato’s method: the theme of the righteousness of the soul is revealed not through the example of the whole state (сf. 369a), i.e., reasoning from the greater to the lesser, but rather through individual examples of the lead characters, Socrates and Thrasymachus. From the ancient text, only these two maintain their significance in the new plot, assuming the roles of a protagonist and antagonist, respectively. There is no mention of Cephalus, Polemarchus Adeimantus, and Glaucon. In turn, some other characters mentioned by Plato appear in Marchand’s book with the main figures, in particular Homer, Damon the musician, the Goddess of Destiny and the three Judges, who represent the three parts of the soul – a many-headed bronze beast seeking pleasure, a silver lion representing justice and a golden man personifying reason. Unlike the ancient text, here, parts of the soul are first identified with the metals of which the soul is composed (the coloured illustrations also support this) and second, they function as the Three Judges of the Underworld.

The book has an entirely different structure than Plato’s dialogue. Instead, it starts with the philosopher's death, leading to his rebirth in other reincarnations. The further sequence of themes also does not correspond to the classical text. Using new combinations of fragments, Marсhand creates a mosaic. The allusions in the short story may be mapped as follows: a transition from Plato’s book I with the themes of afterlife and justice (330d–338b) to books X and IX, concerning the immortality and the structure of the soul (611a–621d; 580d–583b), then to book I on the justice understood as the power of the strongest, according to Thrasymachus (336b–d, 338c, 343c, 344c, 348c–349a), and – when the characters get to Kallipolis – to books III (403d–417b), II (376e) and IV (489c–493a) on the education and daily life in the perfect state followed by references to book V (455b–d), when discussing the role of women. Subsequently, book X (595a–611a) is the main source for the fragment with an enraged Homer (also cf. 379d–e of book II), book VII, the Platonic dialectics (531d–535a) and the allegory of the Cave (514a–520a), book VI, the Sun representing the Good (504е–509с), book VIII describes the soul of a tyrant (562a–564c) and finally book X (615c–616a), the story of the tyrant, Ardiaeos.

The plot involves three reincarnations of Socrates and Thrasymachus and, more specifically, the aspiration of Socrates to improve Trasymachus’ soul during his attempts to escape his millennial punishment after another unjust life. Therefore, the conflict between these “frenemies” is clearly related to Socrates’ words in Plato’s section 498c–d: “Do not try to breed a quarrel between me and Thrasymachus, who have just become friends and were not enemies before either. For we will spare no effort until we either convince him and the rest or achieve something that will profit them when they come to that life in which they will be born again and meet with such discussions as these.” That is why the results of their metempsychosis take on a special symbolism. During the first reincarnation, Thrasymachus turns out to be an orator, so eager for money and the people’s sympathy that he is even willing to defend a criminal during the trial. At the same time, Socrates appears as a gadfly, which suggests a parallel first, to his words in Plato’s text (“[the tyrannized soul is] always perforce driven and drawn by the gadfly of desire it will be full of confusion and repentance,” 577e), and second, to a passage from the Apology of Socrates, in which he compares himself to μύωψ ([muops], “gadfly”), a gadfly required for a horse that “needs to be aroused by stinging”** (Plat. Apol. 30e).

In the second rebirth, already in the ideal Kallipolis, Thrasymachus becomes an artisan producing beds, making it possible to explain the concept of the three classes and the theory of Forms and characterise him as a man whose soul is predominantly composed of iron and copper. These metals correspond to the bronze colour of the pleasure-seeking, multi-headed animal part of the soul depicted in the book. This again determines his pursuit of the fake Good, e.g., the attempt to kidnap the queen for ransom. It is worth noting, however, that in Marchand’s book, the producer-Thrasymachus states that his parents predetermined his class and he could not have been anything else (p. 41), whereas according to Plato, children may have a different concentration of metals in their soul and thus may belong to a different group (415b–d). In this life, Socrates is Homer’s dog. This is significant because he often exclaims “νὴ τὸν κύνα!” ([ne ton kuna], “by the dog!”). Also, because in Laws, Plato states that poets compared philosophers to “dogs howling at the moon”*** when they tried to explain celestial phenomena using reason (XII 967b–c). Nevertheless, the philosopher is, here, a seeing-eye dog for the blind poet (both literally and metaphorically).

Finally, the last described reincarnation explains the metaphor in the title of the book. From what shadows does Socrates step out, and where does he go? This time, Thrasymachus lives as a tyrant, and the philosopher becomes an inhabitant of the Cave. Despite all the obstacles, Socrates stays true to his quest for truth (or the Sun as the Good, cf. 507e–508d) and manages to leave the Сave and see things as they are. Both characters are rejected by society. They find themselves back in the netherworld, Socrates because of his desire for enlightenment, Thrasymachus because of his need for false values. The first will get another reward, and the second will be sent to Tartarus. This book is about rising from darkness to light through justice and wisdom. Dialectics become the right tool to see things in their genuine Form.

As in Yan Marchand’s other books, there is a lot of valuable cultural details. For instance, Marchand mentions that Socrates respects his death sentence by drinking a poison hemlock infusion; a celebration in honour of Apollo and a mission to Delos unfolds as a background, and Sophocles – also appearing in Plato’s text (cf. 329b–d) – is mentioned (although at the time he was already dead). Plato himself is mentioned, among others, as Socrates’ friend and author of the idea of the most-just city (p. 32). Thus, the children’s story receives an element of meta-textuality and becomes not only an adaptation of the dialogue but also a book about it.

* All quotations from: Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 5 & 6, trans. Paul Shorey, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, London: William Heinemann Ltd. 1969. Available online in the Perseus Digital Library (accessed: November 26, 2021).

** Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1, trans. Harold North Fowler, Cambridge: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1966. Available online in the Perseus Digital Library (accessed: November 26, 2021).

*** Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vols. 10 & 11, trans. R.G. Bury, Cambridge: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1967, 1968. Available online in the Perseus Digital Library (accessed: November 26, 2021).

Further Reading

Annas, Julia, An Introduction to Plato’s Republic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Ferrari, Giovanni R. F., ed., The Cambridge Companion to Plato’s Republic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Murphy, Neville Richard, The Interpretation of Plato’s Republic, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951.

Piechowiak, Marek, Plato’s Conception of Justice and the Question of Human Dignity, Berlin: Peter Lang, 2021.

Plato, Republic, Volume I: Books 1–5, trans. Christopher Emlyn-Jones and William Preddy, Loeb Classical Library 237, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Santas, Gerasimos, ed., The Blackwell Guide to Plato’s Republic, Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.