Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Dorota Terakowska, Samotność bogów. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1998, 207 pp.

ISBN

Awards

1998 — Book of Spring by Poznań Review of New Releases;

1998 — Book of the Year by the Polish section of IBBY.

Genre

Bildungsromans (Coming-of-age fiction)

Magic realist fiction

Time-travel fiction

Target Audience

Crossover

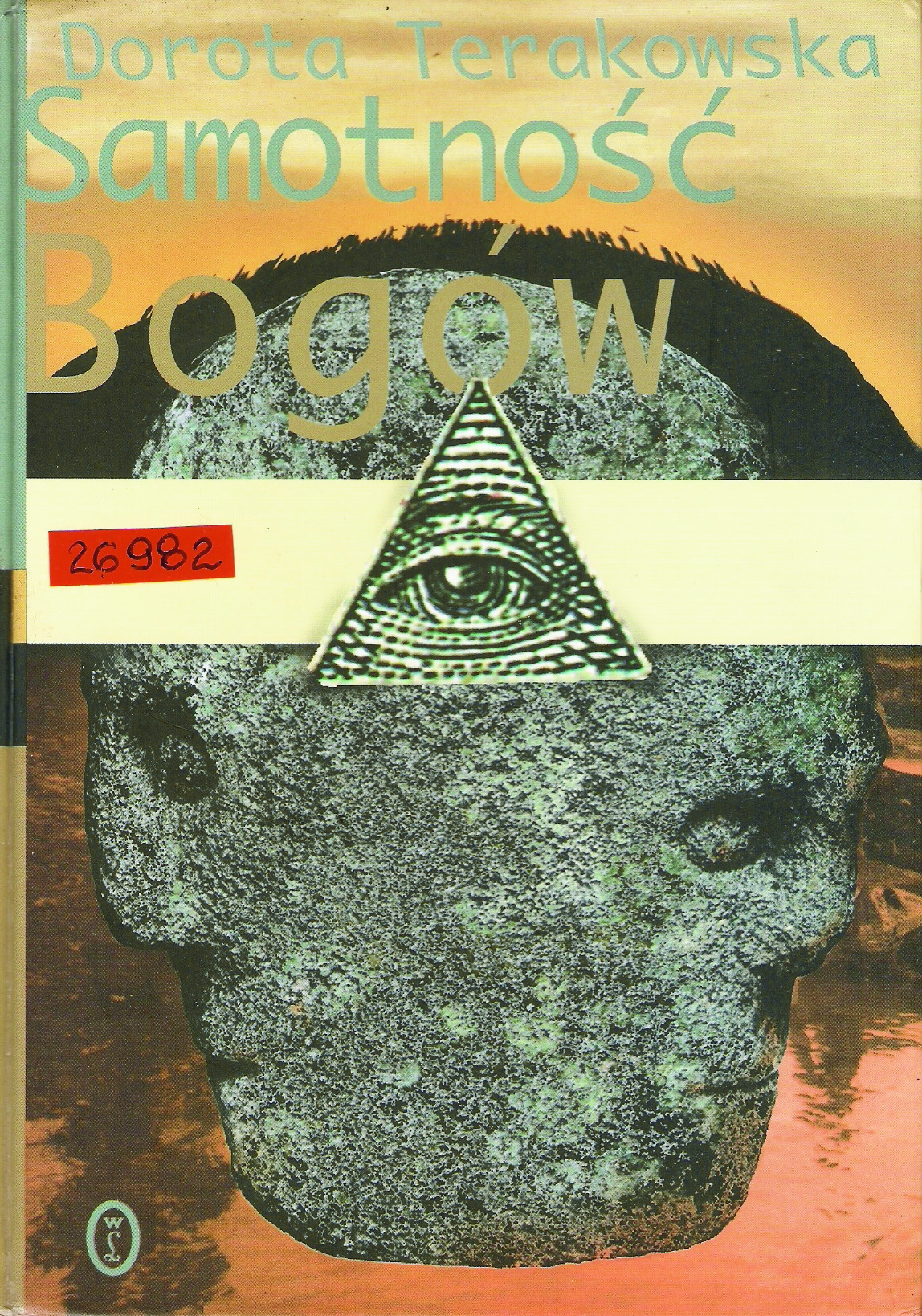

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Konrad Tymoteusz Szczęsny, University of Warsaw, k.t.szczesny@gmail.com

Analysis: Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph courtesy of Katarzyna T. Nowak, the Author’s Daughter.

Dorota Terakowska

, 1938 - 2004

(Author)

Born in Kraków, Dorota Terakowska was a writer and journalist. She received an MA in sociology at the Jagiellonian University (1965). She was an editor-in-Chief of “Gazeta Krakowska” (1969–1981), editor and commentator for the national weekly published in Kraków, “Przekrój” [Cross-section] (1976–1989), and for “Zeszyty Prasoznawcze” [Press Studies]; a member of Stowarzyszenie Dziennikarzy Polskich [Polish Journalists Association] (1971–1981) and Stowarzyszenie Pisarzy Polskich [Polish Writers’Association] (from 1989). She debuted with the novel Guma do żucia [Chewing Gum], 1986; established herself as one of the most successful fantasy writers for children, teenagers and popular among adults. She received many prestigious awards: in 1994, she was placed on the Hans Christian Andersen Honour List; she received three prizes from the Polish Section of IBBY for Córka czarownic [Daughter of the Witches], 1991; Samotność bogów [Loneliness of the Gods], 1998, and Tam gdzie spadają anioły [Where the Angels Fall], 1999, and also the 1995 Children’s Bestseller for Lustro pana Grymsa [Mr Gryms’ Mirror] awarded by a jury composed of children; the 1998 Book of Spring for Loneliness of the Gods and was nominated in 1998 for Paszport “Polityki” [“Polityka” Pass], an annual cultural award of the weekly “Polityka.” Terakowska’s two daughters also had successful careers: Katarzyna T. Nowak became a journalist and writer, and Małgorzata Szumowska became a film director.

Sources:

Nowak, Katarzyna T., Moja mama czarownica. Opowieść o Dorocie Terakowskiej [My Mother the Witch. A Story about Dorota Terakowska], Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2005.

Official website (accessed: April 2, 2022).

Wydawnictwoliterackie.pl (accessed: April 2, 2022).

Bio prepared by Konrad Tymoteusz Szczęsny, University of Warsaw, k.t.szczesny@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Based on Slavic mythology and Christian beliefs, it also includes socio-psychological motifs. Jon is a young boy who heard “the call” the day he was able to rescue his future wife from drowning in a nearby river: he now has to transform his life. He travels through different times and places and takes many other forms with the mission to help the old Slavic god, Światowid [The One Who Sees the World], to drift away. He visits the present time (as a doctor), goes back to the Middle Ages (where he plays a role in the life of Joan of Arc) and then even further into the past, to the beginning of the new era, where he meets Jesus Christ. Jon dies at the end, but his mission is complete: the statue of Światowid falls apart, and he has a revelation of the imminent arrival of the new age, a time of love and understanding, without any religious conflicts; gods will thank their apostles for their faith, love and courage and will return their love to the people. This is the message from Światowid: “Przybędziemy, ludzie, zstąpimy, żeby oddać wam waszą miłość… Nie zabijajcie nas zbyt wcześnie…” (We will come, people, we will descend, to return your love… Don’t kill us too soon…, p. 245).*

* References based on the edition: Terakowska, Dorota, Samotność bogów, Kraków: Wydawnictwo literackie, 2003.

Analysis

The text, however, does not directly reference classical mythology. It reflects life in a society that still remembers old beliefs and myths, but has accepted new, in this case, Christian, beliefs (i.e., faith in the God of Goodness). Although pagan beliefs presented in the book are of Slavic origin, the text may, by analogy, give an insight into life during Late Antiquity when Christianity had already made the old pagan cults obsolete. However, the text may be of particular interest to young Christian readers and address possible questions about the coexistence of different religious and mythological narratives. The sympathetic portrayal of old gods enhances the value of ancient Slavic culture. It encourages the readers to explore their culture and reflect on the nature of faith (cf. p. 178).* In the description of the return of all gods, Greek and Roman gods (Zeus / Jupiter, Priapus) are mentioned, among others (pp. 237, 244).

According to the novel, pagan gods were created by the beliefs of the faithful themselves (p. 34), an assumption which also determined the gods’ character (for example, the severity and cruelty of Światowid). The fanatical take on Christianity is embodied in the God of Goodness, bestowed with the harsh, bloodthirsty and intolerant aspects of the pagan gods, which is evident in Ezra’s sermons and the episode involving Joan of Arc. Although it is said that the God of Goodness existed before gods and people came to be, people’s faith was not a condition of his existence; his image is subject to human interpretation and like Światowid, he becomes a more severe deity.

Another important aspect of the novel is how doubt is shown as another way of thinking (pp. 189, 255); it allows greater openness and wisdom. It is the main characteristic of the old priest Isak’s mentality and Jon’s way of thinking. However, Jon does everything he can to raise his son to be a man without any doubts, who fits into the new world and is closer to the fanatical priest Ezra (pp. 128, 150). Indeed, Ezra perceives Bogumił as his best disciple. Nevertheless, in the end, Bogumił also hears the distant call of Światowid and finds comfort in the “warm pulse” of the stones from the ruin of the god’s statue, where Jon had died (p. 255).

The theme of exclusion from society is also present in the novel, in the story of Ariel, a former jester, originally a member of a foreign migratory tribe and a friend of Jon and Gaja. Jon advises him and Gaja to leave the village and travel the world when Bogumił is grown enough to start studying at the priests’ school.

The novel asks questions about faith, tolerance, the courage required to think and love, destiny and sacrifice in the name of the highest possible values.

* References based on the edition: Terakowska, Dorota, Samotność bogów, Kraków: Wydawnictwo literackie, 2003.

Further Reading

Olszański, Tadeusz A., “Baśń nie nowa i nie mądra”, Biuletyn Śląskiego Klubu Fantastyki 114 (1999), available here (accessed: April 2, 2022).

Śliwiński, Piotr, “Czar padł”, Megaron, VII/VIII (1998), available here (accessed: April 2, 2022).

Thaidigsmann, Karoline, “Post-Socialist Identity between Slavic Gods, the Graeco-Roman, and the Christian Tradition. A Reading of Dorota Terakowska’s Crossover Novel The Loneliness of the Gods”, in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical History: Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture in Response to the Heritage of Ancient Greece and Rome, Warsaw: Warsaw University Press, 2022, forthcoming.

Thaidigsman, Karoline, Poetik der Grenzverschiebung. Kinderliterarische Muster, Crosswriting und kulturelles Selbstverständnis in der polnischen Literatur nach 1989, Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter, 2022, forthcoming.