Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Halina Rudnicka, Syn Heraklesa. Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1966, 414, [2] pp.

ISBN

Genre

Historical fiction

Target Audience

Crossover

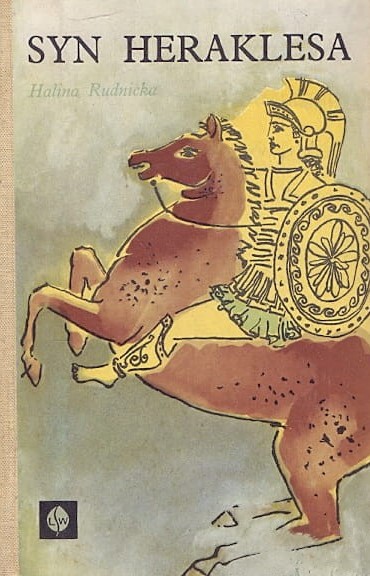

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Michał Kucharski, University of Warsaw, kucharski.michal@al.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph from Janusz Dębski’s archive.

Halina Rudnicka

, 1909 - 1982

(Author)

Born in Mława. A writer, publicist, educator, and author of textbooks. Most known for writing books inspired by Antiquity and aimed at young adults. Graduated from the University of Warsaw with MA in Polish philology. She later completed a post graduate degree in pedagogy. During the German occupation she took part in the underground education of Polish children. After WW2 she worked at the Ministry of Education right up to 1949, and then devoted herself to writing full time.

The beginning of her literary career coincided with the 5th Congress of Polish Writers at which social realism was imposed as the leading literary style. As a result, most of her books display a strong influence of the social realism. Her major works: Polną ścieżką [Through Field Path], 1949; Chłopcy ze Starówki [Lads from the Old Town], 1960 – books referring to WW2 and Nazi German occupation of Poland; Płomień gorejący [Ardent Fire], 1951 – a biography of Felix Dzerzhinsky aimed at young adults, and Wspomnienia o Janku Krasickim [Memoirs about Janek Krasicki], 1955 — a story of the young Polish activist and agitator for USSR. Rudnicka is also the author of Trylogia spartańska [Spartan Trilogy] — a series of three novels for young adults: Król Agis [King Agis], 1963; Syn Heraklesa [The Son of Heracles], 1966, and Heros w okowach [A Hero Bound], 1969.

She was the recipient of many Polish and international awards, e.g. the Polish National Award (2nd Rank) for her novel Uczniowie Spartakusa [The Disciples of Spartacus], 1951, the Prime Minister’s Award for her books for children and teens. In 1979 her novel Uczniowie Spartakusa gained a place on the Hans Christian Andersen Honour List.

Sources:

Janusz Dębski, "Halina Rudnicka – pisarka z Mławy", kuriermlawski.pl (accessed: February 21, 2013).

Hanna Kanigowska, "Patron", zpo2.mlawa.pl (accessed: June 11, 2021).

"Rudnicka Halina", in Julian Krzyżanowski, ed., Literatura polska. Przewodnik encyklopedyczny, vol. II: N–Ż, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1985, 318–319.

Bio prepared by Helena Płotek, University of Warsaw, helenaplotek@student.uw.edu.pl

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Halina Rudnicka, Król Agis, Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1963, 456 pp.

Halina Rudnicka, Heros w okowach, Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1969, 302 pp.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

This is the second part of the Spartan Trilogy (see part 1, part 3). After the death of King Leonidas, Sparta is ruled by his son Cleomenes. Unlike Leonidas, the new king approved the socio-political reform of the Spartan state that Agis failed to impose. In the first period of his reign, Cleomenes is completely under the control of the ephors – the five annually elected leaders; he attempts to increase his political importance by conducting successful wars against the Achaean League. Having become a military hero (Cleomenes is acclaimed by his companions “the Son of Heracles”), he succeeds in having four of the five ephors killed and abolishes the ephorate. He reforms Sparta and reestablishes the institutions of Lycurgus – fulfilling Agis’ dream of a great and powerful Sparta. In the subsequent armed conflicts with the Achaeans, who the Macedonians support, Cleomenes is defeated and effectively forced to leave Sparta. He flees to Alexandria, hoping that king Ptolemy will help him return to Sparta and regain the throne.

Analysis

The novel is set in Sparta and the Peloponnesian lands between 240–222 BC. It covers the life of Cleomenes III, son of Leonidas II of the Agiad line, from the death of Agis IV until the battle of Sellasia. The course of main events and even some minor subplots mainly follow the version of Plutarch in the Life of Cleomenes (1.1–31.6) and Aratus (2; 35.4–46.1) with some direct quotations (marked in footnotes). Rudnicka treats Plutarch’s story as a background to build characters of major and minor importance and highlight social and political issues like agrarian reforms or the coup d’état.

The exposition presents the life of Spartan youths at a gymnasion, where young Cleomenes is raised along with his companions according to the Spartan agoge rules. He is treated as strictly as the others and has no privileges despite being the king’s son. His boyhood ends when he is summoned to his father, who imposes on him a marriage with Agiatis, the young queen dowager of the murdered Agis IV. The scene shows Cleomenes, his mother Cratesicleia, Agiatis and her father Gylippus, out of fear, are all entangled in Leonidas’ political game, each of them unable and unwilling to oppose the king, all being used as his pawns. Unlike his father, the young royal son is presented, from the beginning, as an extraordinary person of noble spirit: the author follows in her description of Plutarch’s way of highlighting the moral virtues of the positive characters as role models to be followed. However, the character of Cleomenes is not presented as entirely flawless as King Agis was in the last part of the Spartan trilogy. Since Rudnicka uses ancient sources, the facts do not allow her to make her protagonist perfect. The character seems to be more authentic and multidimensional than Agis. Although Cleomenes wants to be the heir of Agis’ ideas, principles, and plans of reforming Sparta, he acts differently and is shown as a flesh and blood person, exceptional but with some imperfections.

Cleomenes tries to make Sparta great again on both external and internal fronts. What differentiates him from his predecessor, Agis, is his planning of a coup in his homeland in full awareness that the bloodshed cannot be avoided. This is the difference between him and Agis, who refused to abuse power towards Spartan citizens even if it could save his life, each time opting for bloodless solutions. Cleomenes, however, calculates potential profits and losses for the sake of Sparta as he understands its welfare. Eventually, he feels justified, even if he had doubts before. The political assassination of the ephors is commented as a necessary part of the revolution: “Life is priceless […] each of us, however, is willing to sacrifice it for the sake of Sparta. And the ephors gave their lives because they did not want to save Sparta. Let’s strengthen the power of justice.” (p. 162*). The king treats the power of the ephors as the power of usurpers (p. 164); he is glad above all that there are not many victims of the revolution (p. 162). He explains again that the legal way of removing this “misfortune of Sparta” was impossible to accomplish, so it was necessary to use violent means (p. 165). Cleomenes’ approach to a political assassination is also evident in his attitude toward Aratus of Sicyon, his enemy. Aristomachos of Argos explains that he is not a promoter of political murder. If he were, Aratus would have been dead a long time ago, as he had several opportunities to take revenge on Aratus for his harm. Cleomenes, however, answers: “it is really bad he is still alive […], I will not be so clement if I catch him” (p. 186). Rudnicka somehow absolves Cleomenes from committing murder and allows the protagonist to explain his motives and purposes. Still, her way of explanation is not that he acts as a man of an ancient culture where mercy towards foes seems to be unusual and exceptional, but that he acts in the name of the revolution. What is more, Aristomachos of Argos, who does not want political repressions towards followers of Aratus and prefers to persuade, not push opponents, is eventually punished – his politics cost him his life as followers of Aratus seeking revenge, kill him. This way, the reader can see that opponents of the revolution are abominable characters not worth anybody’s pity.

What sparks particular interest is the attitude towards the slavery of the helots. Cleomenes as a young man, is a sensitive person; when his relatives think he went for a krypteia – a hunt for a helot, in fact, he just needed some time to be alone and conversely – he helps a helot to save his son, takes care of him and even gives him his mantle. But this is the act of kindness towards a man and not a system solution to improve the lot of all helots. While Agiatis, raised on the ideas of her late husband, states that the revolution should go a step further and give equality to helots as they are also human, Cleomenes is not convinced that the time for their freedom has come. He can sell rights to citizenship for those metoikoi who can buy their freedom by serving in the army and ransoming themselves in a situation where money and soldiers are needed. Still, he cannot even imagine that universal emancipation could be feasible.

In the end, Cleomenes gains respect despite having been defeated. Antigonus III Doson, his Macedonian foe, does not want revenge on the Spartans as he appreciates Cleomenes’s bravery, courage, and uniqueness. He states, “After all, glory to the vanquished” (p. 292).

Further Reading

De Pourcq, Maarten, and Roskam, Geert, “Mirroring virtues in Plutarch’s Lives of Agis, Cleomenes and the Gracchi” in K. De Temmerman and K. Demoen, eds., Writing Biography in Greece and Rome: Narrative Technique and Fictionalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 163–180.

Fuks, Alexander, “Agis, Cleomenes, and Equality”, Classical Philology 57.3 (1962): 161–166 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives, with an English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1921; Greek; English (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Roskam, Geert, “Ambition and Love of Fame in Plutarch’s Lives of Agis, Cleomenes, and The Gracchi”, Classical Philology 106.3 (2011): 208–225, doi:10.1086/661543 (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Smith, Philip, "Cleomenes III" in William Smith, ed., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1867, 793–795, (accessed May 23, 2022).

Stabryła, Stanisław, Hellada i Roma w Polsce Ludowej. Recepcja antyku w literaturze polskiej w latach 1945–1975, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1983, 225–228.

Sucharski, Robert A., Halina Rudnicka and Her Ancient Trilogy or On the Nature of the True Hero(in)es, in: Our Mythical Nature volume, 2022 (soon in print).

Addenda

Graphic design – Karol Syta.