Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Halina Rudnicka, Heros w okowach, ill. Karol Syta. Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1969, 302 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Historical fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (Children over 10 years old, teenagers, young adults)

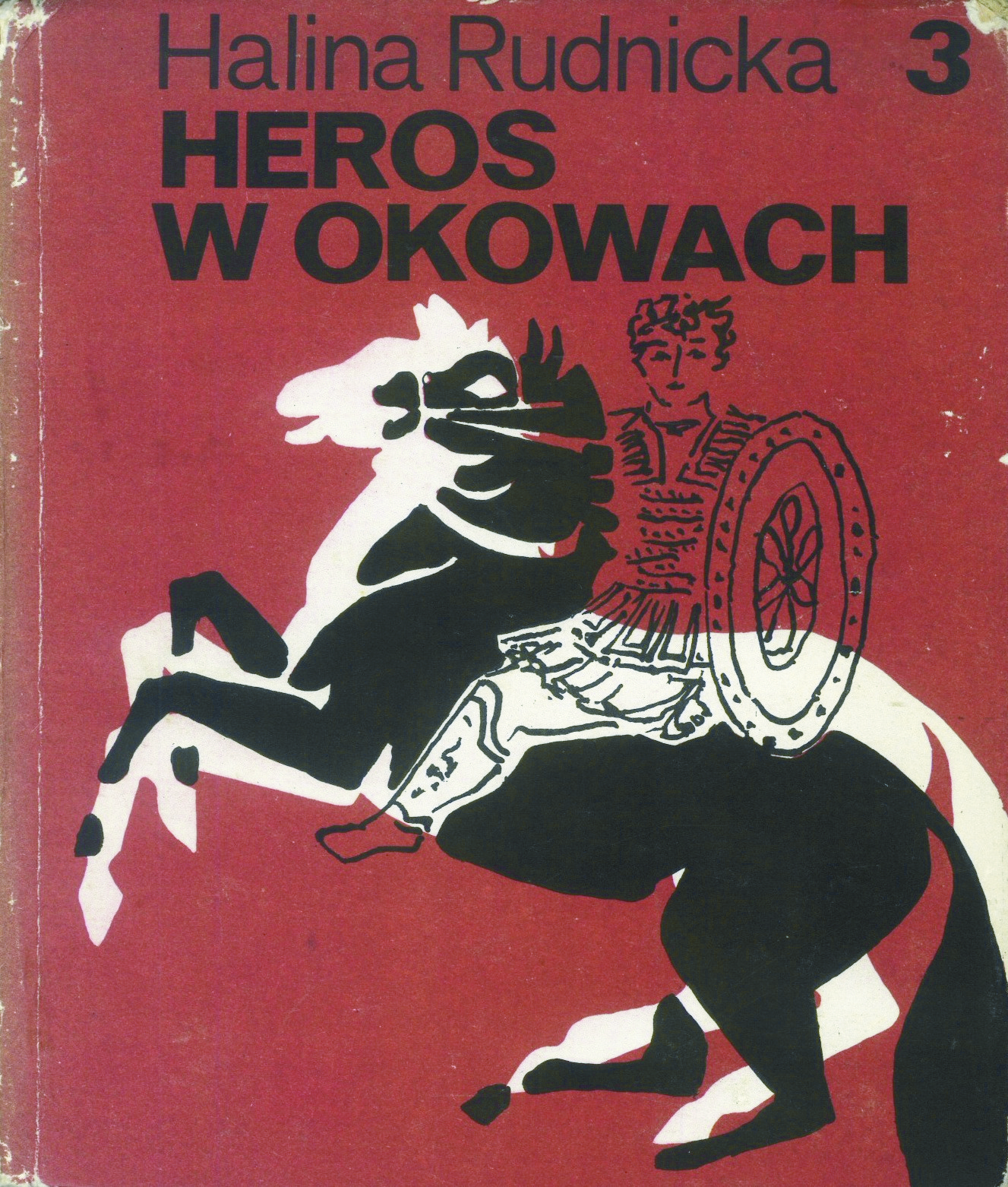

Cover

Cover design and illustrations by Karol Syta. Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Joanna Grzeszczuk, University of Warsaw, joannagrzeszczuk1@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph from Janusz Dębski’s archive.

Halina Rudnicka

, 1909 - 1982

(Author)

Born in Mława. A writer, publicist, educator, and author of textbooks. Most known for writing books inspired by Antiquity and aimed at young adults. Graduated from the University of Warsaw with MA in Polish philology. She later completed a post graduate degree in pedagogy. During the German occupation she took part in the underground education of Polish children. After WW2 she worked at the Ministry of Education right up to 1949, and then devoted herself to writing full time.

The beginning of her literary career coincided with the 5th Congress of Polish Writers at which social realism was imposed as the leading literary style. As a result, most of her books display a strong influence of the social realism. Her major works: Polną ścieżką [Through Field Path], 1949; Chłopcy ze Starówki [Lads from the Old Town], 1960 – books referring to WW2 and Nazi German occupation of Poland; Płomień gorejący [Ardent Fire], 1951 – a biography of Felix Dzerzhinsky aimed at young adults, and Wspomnienia o Janku Krasickim [Memoirs about Janek Krasicki], 1955 — a story of the young Polish activist and agitator for USSR. Rudnicka is also the author of Trylogia spartańska [Spartan Trilogy] — a series of three novels for young adults: Król Agis [King Agis], 1963; Syn Heraklesa [The Son of Heracles], 1966, and Heros w okowach [A Hero Bound], 1969.

She was the recipient of many Polish and international awards, e.g. the Polish National Award (2nd Rank) for her novel Uczniowie Spartakusa [The Disciples of Spartacus], 1951, the Prime Minister’s Award for her books for children and teens. In 1979 her novel Uczniowie Spartakusa gained a place on the Hans Christian Andersen Honour List.

Sources:

Janusz Dębski, "Halina Rudnicka – pisarka z Mławy", kuriermlawski.pl (accessed: February 21, 2013).

Hanna Kanigowska, "Patron", zpo2.mlawa.pl (accessed: June 11, 2021).

"Rudnicka Halina", in Julian Krzyżanowski, ed., Literatura polska. Przewodnik encyklopedyczny, vol. II: N–Ż, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1985, 318–319.

Bio prepared by Helena Płotek, University of Warsaw, helenaplotek@student.uw.edu.pl

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Halina Rudnicka, Król Agis, Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1963.

Halina Rudnicka, Syn Heraklesa, Warszawa: Ludowa Spółdzielnia Wydawnicza, 1966.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp., section by Joanna Grzeszczuk, p. 322.

A Hero Bound is the last book of Halina Rudnicka’s trilogy about ancient Sparta. The Spartan king Cleomenes, after being defeated by the Achaean League, flees to the court of Ptolemy Euergetes in Egypt. He is hoping for help in regaining his throne in Sparta. Unfortunately, Egyptian king dies; he is succeeded by his son Ptolemy Philopator. At the suggestion of his unforgiving and power-hungry advisors, Sosibius and Agathocles, Ptolemy commands to prepare assassination of his young brother Magas. Soon afterwards he passes a sentence on his mother, noble and wise Berenice. King Cleomenes, who also fears for his life, tries to find a way to escape from Alexandria, but he is accused of conspiracy and put under home arrest. In company of a few Spartans, he flees from the guarded villa. However, some of his friends, who promised to help him, let him down. He is forced to commit suicide because he wants to die as a free man. The next day the judgment is enforced on his family, his mother and sons. In this tragic way ends the glorious Agiad dynasty, descendants of Heracles.

Analysis

Rudnicka sets her novel in Hellenistic Alexandria between 222–219 BC and describes the fate of post-Sellasian fugitives from Sparta: king Cleomenes III, his family and loyal friends. The sequence of historical facts presented by the author is based on ancient sources, first of all, on Plutarch’s Life of Cleomenes (32–38), Polybius’ The Histories and Pausanias. It is enriched with a detailed background against which the protagonists seem more credible. The characters are presented as an element of a dangerous political game of the Ptolemaic court where the former Spartan king is only a pawn.

The main figure in this play is Sosibius, unfriendly to the Spartan exiles, a powerful player and a grey eminence of the Egyptian state, even more powerful than the king himself. Cleomenes realizes that after the acceptance and generous support granted by the old Ptolemy Euergetes, his descendant is not as favourable as his father since his preferred occupation is debauchery. Corrupted with wine and women, he keeps pretending to be Dionysus and leaves politics to his counselors. Inside the court, even the lives of the king’s relatives can be in danger – Magas, more popular than his elder brother, gets “mistakenly” assassinated, Berenice, the queen-mother, is forced to commit suicide using the venom of a cobra. Cleomenes chooses between being a servant to a master he despises or – like Achilles – living a famous but short life. He starts losing hope as his affairs are neglected, and he becomes a potential danger for the Ptolemaic state. He is deprived of a luxurious palace given to him by the old king and 24 talents of allowance. The Spartans are forced to move to a humble dwelling situated in a worse district and placed under guard. They try to return to their homeland, but the attempts at fleeing and organizing a rebellion with the Alexandrians fail, as the inhabitants do not follow them. The situation comes to an end – a group of twelve lonely Spartiates fall on their swords as for them, there is no other freedom but death. Cleomenes, preserving the Spartan pride, honour and tradition, tells them that whoever wants to die free must take his own life. According to Plutarch, "he hoped they would all die in a manner that would reflect no dishonour upon him, or on their own achievements"*. Though his corpse is desecrated and dishonoured, his greatness is evident for the Alexandrians when they see a clear omen: a huge snake appears and protects the deceased’s face from scavenger birds. This sign elevates Cleomenes to a larger than life, real hero, son of the gods, and thus his legend starts spreading.

Cleomenes is the novel’s main character; the lesser characters are also described in historical detail. Among the Spartans are king’s sons, a mother and a captive native of Megalopolis, a Spartan envoy, Mandrocleidas with his son Nabis – a future Spartan king (in fact, the son of Demaratos), and other soldiers known by name (Panteus, Hippitas), along with their wives. On the Egyptian side, the reader encounters members of the Ptolemaic dynasty: Ptolemy III Euergetes, his wife Berenice and children, Ptolemy Philopator, Magas and Arsinoe. The omnipotent minister Sosibius, young Ptolemy’s favourite Agathocles and his sister, and Eratosthenes of Cyrene called “Beta”, director of the Library, the greatest scholar of those times. They are all historical figures and are described in vivid detail as well. Another minor character, the man responsible for the denunciation and false accusation of Cleomenes leading to his eventual death, Nicagoras the Messenian, is mentioned by Plutarch as someone who was once refused payment for a piece of land and sought revenge for this.

The silent protagonist of great importance is the city of Alexandria, a lively society of many contrasts. At first, it is presented as a gilded cage; describing the wealth of the Brucheion district that the Spartans had not known before and with the splendour of the royal Ptolemaic court. Alexandria appears, however, to be much more than this. Also, the Rhakotis district, port and Pharos are present in the novel, along with city institutions such as theatre, the Dionysia festival, the Ptolemaia festival and games, and the Museion with its zoo. Description of many customs, cultural traditions, cults or religious rites enriches the background and allows the reader to learn about the diversity of the Hellenic community in Egypt.

The intertextuality of the novel is also worth mentioning. Protagonists are well educated and quote ancient masters, such as Euripides, Aristotle or Callimachus. The old Ptolemy likes lyrical poetry by Anacreon and Sappho. The young Ptolemy writes and performs his own comedy about the wedding of Dionysus and Ariadne, and likes to show off his erudition, even though he is considered to be an educated person but not wise because he quotes without a deep understanding of the content.

Social issues are prominently displayed in the novel, which is understandable, as Cleomenes implemented reforms of law, administration, economy and social issues. His views and statements about it, however, are sometimes highlighted by the author and negatively assessed. In some cases, she employs the language of Marxist slogans, vocabulary and phraseology to describe the leading class as abominable and oppressive.

* Life of Cleomenes 37, 12.

Further Reading

"Cleomenes III", in William Smith, ed., A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1867, 793–795, quod.lib.umich.edu (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Fuks, Alexander, "Agis, Cleomenes, and Equality", Classical Philology 57.3 (1962): 161–166. (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Καβάφης, Κωνσταντίνος Πέτρου (Cavafy, Constantine P.), “Άγε, ω βασιλεύ Λακεδαιμονίων” (Come, O King of the Lacedaimonians) in Τα ποιήματα Β' (1919–1933) [Ta Poiímata, vol. 2 (1919–1933)], ed. G. P. Savvidis, Ίκαρος [Ikaros], 2014; online (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Μαυροκεφάλου, Λιλή [Mavrokefalou, Lili], Κλεομένης [Kleoménis], Αθήνα [Athens]: Eκδόσεις Κέδρος [Ekdósis Kédros], 1981.

Μιχαλόπουλος, Μιλτιάδης [Michalopoulos, Miltiadis], Εις το όνομα του Λυκούργου: η άνοδος και η πτώση του επαναστατικού σπαρτιατικού κινήματος (243–146 π.Χ.) [Eis to ónoma tou Lykoúrgou: i ánodos kai i ptõsi tou epanastatikoú spartiatikoú kinímatos (243–146 BC)], Αθήνα (Athens): Eurobooks, 2009.

Plutarch, Plutarch's Lives with an English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1921; Greek; English (accessed: July 6, 2021).

Ροδάκης, Περικλής [Rodakis, Perklis], Κλεομένης Γ’: Η μεγάλη Κανωνική Επανάσταση [Kleoménis ΙΙΙ: I megáli kanonikí epanástasi], Αθήνα [Athens]: Eκδόσεις Καστανιώτη [Ekdóseis Kastanióti], 1994.

Roskam, Geert, "Ambition and Love of Fame in Plutarch’s Lives of Agis, Cleomenes, and The Gracchi", Classical Philology 106.3 (2011): 208–225, doi:10.1086/661543 (accessed: July 6, 2021). February 8, 2021.

Stabryła, Stanisław, Hellada i Roma w Polsce Ludowej. Recepcja antyku w literaturze polskiej w latach 1945–1975, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1983, 225–228.

Βέρσης, Κωνσταντίνος Χ. [Versis, Konstandinos Ch.], Κλεομένης ο τελευταίος Ηρακλειδής [Kleoménis o teleftaíos Irakleidís], εκ του Τυπογραφείου Παρνασσού, Αθήνησιν (Athens: Parnassos Publishing), 1878.