Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

David Almond, Skellig. London: Hodder, 1998, 170 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

Davidalmond.com/skellig/ (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Awards

1998 – Carnegie Medal;

1998 – Whitbread Children’s Book of the Year Award.

Genre

Magic realist fiction

Target Audience

Children

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Sarah F. Layzell, Independent Researcher, sarahlayzellhardstaff@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

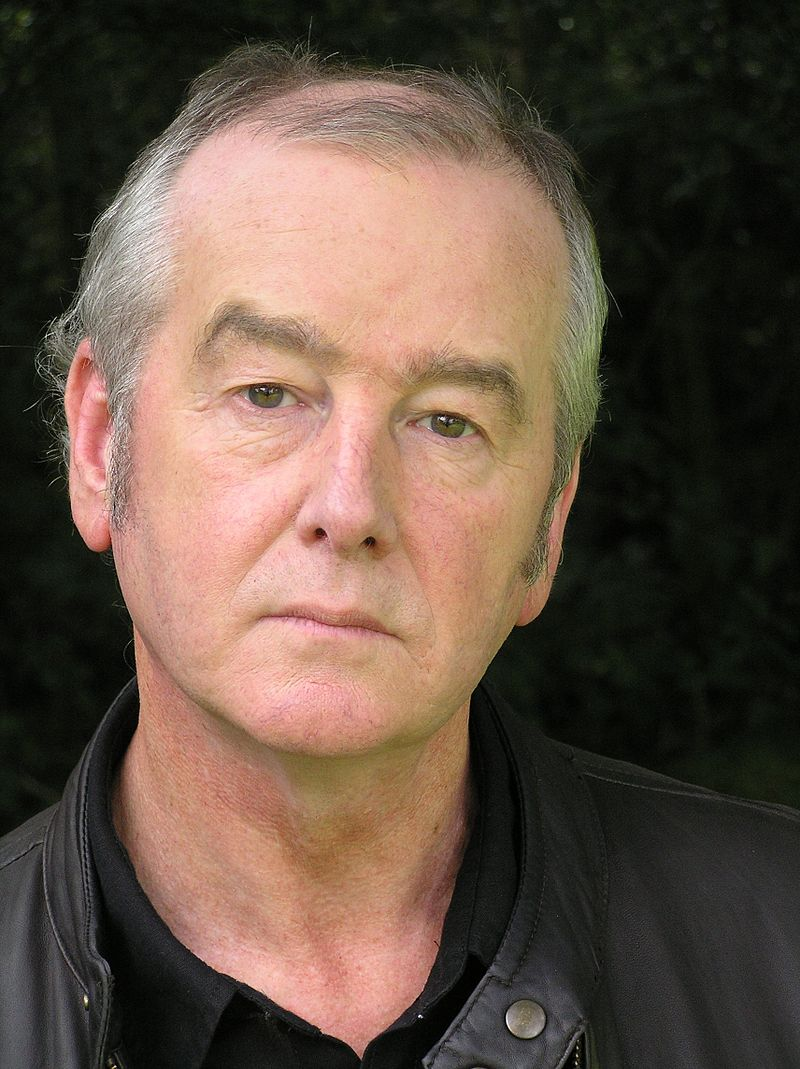

Retrieved from Wikipedia, public domain (accessed: December 21, 2021).

David Almond

, b. 1951

(Author)

David Almond was born at Felling on Tyne, near Newcastle, where he now lives. He is the author of over 30 works, including young adult fiction, children’s fiction, picture books, and short story collections. His debut novel, Skellig, won the Carnegie Medal in 1998, kick-starting his career as an author. His work has since been adapted for the screen and stage, as well as translated into over 40 languages. He is currently a Professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University,. In the past, he worked as a teacher and an editor for the literary fiction journal Panurge.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: July 6, 2018)

Profile at goodreads.com (accessed: July 6, 2018)

Twitter (accessed: January 1, 2019)

Bio prepared by Emily Booth, University of Technology, Sydney, Emily.Booth@student.uts.edu.au

Adaptations

Skellig has been adapted as a play, tv-film, and opera. Audiobook and eBook versions of the novel have also been produced:

Audio book: David Almond, Skellig, read by David Almond, New York: Listening Library, 2001.

eBook: David Almond, Skellig [eBook], New York: Delacorte Press, 1999.

Film: Skellig: The Owl Man. Directed by Annabel Jankel, performances by Tim Roth, Kelly Macdonald and Bill Milner, screenplay by Irena Brignull, Feel Films/Taking a Line for a Walk, Sky Television, 2009.

Source: IMDb (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Opera: Tod Machover (Composer) & David Almond (Librettist), Skellig: Opera in two acts.

The opera premiere was performed at the Sage Gateshead in 2008, directed by Braham Murray, choreographed by Mark Bruce, conducted by Garry Walker, and starring Omar Ebrahim as Skellig.

Source: Boosey.com (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Play: David Almond, Skellig: A Play, London: Hodder, 2003.

The play was first performed at the Young Vic Theatre (London) in 2003, directed by Trevor Nunn and starring David Threlfall as Skellig.

Source: Curtainup.com (accessed: September 16, 2022).

Translation

Braille (English): Skellig, Stockport (UK): National Library for the Blind, 1999.

Chinese: 史凱力 (Skellig), trans. Cai Yirong, Xiao lu wen hua shi ye gu fen you xian gong si, 2001.

Czech: Skellig, trans. Veronika Volhejnová, Mladá fronta, 2008.

French: Skellig, trans. Rose-Marie Vassallo, Flammarion, 1999.

German: Skellig, trans. Susanne Heinz, Stuttgart Ernst Klett Sprachen, 2015.

Italian: Skellig, trans. Carola Proto, Mondadori, 2000.

Polish: Skrzydlak, trans. Tomasz Krzyżanowski, Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka, 2010.

Portuguese: Skellig, trans. Waldéa Barcelos, Martins Fontes, 2001.

Russian: Скеллиг [Skellig], trans. Olga Varshaver, Moscow: Inostranka, 2004.

Spanish: Skellig, trans. Laura Emilia Pacheco, Castillo, 2009.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

In 2010, Almond published My Name is Mina, a prequel to Skellig.

Summary

Skellig opens the day after 10-year-old Michael has moved house. His new-born sister is very ill and may not live. He finds what seems to be a homeless man – Skellig – hiding in the dilapidated garage at the new house. Filthy, hungry and in constant pain because of his arthritis, Skellig slowly regains strength as Michael brings him food, beer, painkillers, and companionship.

Michael spends less and less time at school and befriends a neighbour, Mina, who is home-schooled. Michael and Mina decide that Skellig needs to move somewhere safer before the old garage is torn down and guide him to an empty property inhabited by owls. Skellig reveals he has wings.

Meanwhile, Michael’s sister goes into hospital for an operation on her heart: while the baby is in hospital, Michael’s mother dreams about a figure exactly resembling Skellig coming to pick the baby up and saving her life. The operation goes well, and Michael’s sister is no longer at risk of dying. Michael and Mina visit the owl house to say goodbye to Skellig before he leaves them, now recovered and strong.

It isn’t clear whether Skellig is a man, an angel, part-bird, or something else; nor is it clear where he goes at the end of the novel. The novel closes with the family choosing a name for the baby – Joy.

Analysis

Greek mythology is evoked throughout Skellig, both through overt references to myth and through the novel’s plot structure, themes and characterisation. The use of myth is amongst many intertextual references used by Almond, as well as generally contributing to a sense of a timeless story and giving mythic and magical significance to seemingly mundane and everyday details.

The most prominent use of Greek myth is the use of the Persephone story. While Michael’s sister is in hospital, Mina’s mother tells him the story of Persephone, “forced to spend half a year in the darkness deep underground” (p. 137). Mina’s mother makes a connection between the Persephone of myth and Michael’s sister in the hospital, with the effect that when Michael imagines Persephone “struggling her way towards us” from underground, we think of both the goddess and the baby (p. 138). Mina’s mother then prepares a pomegranate for the children to eat, telling them that this “what Persephone ate while she was waiting in the Underworld” (p. 144). When the baby has arrived safely home, Michael suggests calling her Persephone (pp. 149, 170); in the end, the baby is named Joy, following on from Michael’s mother stating they must choose “something very little and very strong” (p. 149) to match the baby herself. This arguably breaks the symbolic link between the baby and the goddess, allowing her to escape the cycles of exile and return. Elizabeth Bullen and Elizabeth Parsons write about how the choice of a non-classical name also reflects Almond’s presentation of different types of knowledge, without privileging the classical, formal or scientific over creative and magical ways of knowing (2007, 143–144).

As well as this connection with the main plot and themes, the Persephone story is evoked in a couple of other ways. From the opening paragraph, we know that “winter was ending” and spring is on the way (p. 1), connecting the novel’s seasonal setting with Persephone’s return. This connection is emphasised by Mina’s mother in her telling of the Persephone myth, which she describes as “a myth that’s nearly true”; “She talked about the way spring made the world burst into life after months of apparent death.” (p. 137) The novel also has its own Hades figure in the baby’s doctor, dubbed ‘Doctor Death’ by Michael (p. 6).

Other mythical figures and stories appear in the novel. Michael’s teacher tells his class the story of Icarus and Daedalus (pp.12–13), linking to the image of Skellig as a winged man. Bullen and Parsons analyse the contrast between Icarus and Skellig, writing, “these two figures are powerfully opposed, not only in terms of technological versus natural wings, but also in terms of optimism. While Skellig needs his optimism to regain strength enough to fly, Icarus’s excessive optimism (hubris) is his downfall.” (2007, 140) The same teacher later tells the class the story of Ulysses and Polyphemus (p. 33); this comes a few pages after Michael asked Skellig who he is and received the answer “Nobody” (p. 28), later repeating the answer “Nobody. Mr Nobody” (p. 54), evoking Ulysses’ conversation with Polyphemus.

Further Reading

Almond, David, “The Necessary Wilderness”, The Lion and the Unicorn 35.2 (2011): 107–117.

Bullen, Elizabeth and Parsons, Elizabeth, “Risk and Resilience, Knowledge and Imagination: The Enlightenment of David Almond’s Skellig”, Children’s Literature 35 (2007): 127–144.

Johnston, Rosemary Ross, “In and Out Of Otherness: Being and Not-Being in Children’s Literature”, Neohelicon XXXVI. 1 (2009): 45–54.

Johnston, Rosemary Ross, ed., David Almond (New Casebooks), London: Macmillan Education, 2014.

Latham, Don. “Empowering Adolescent Readers: Intertextuality in Three Novels by David Almond”, Children’s Literature in Education 39 (2008): 213–226.

Latham, Don, “Magical Realism and the Child Reader: The Case of David Almond’s Skellig”, The Looking Glass 10.1 (2006).