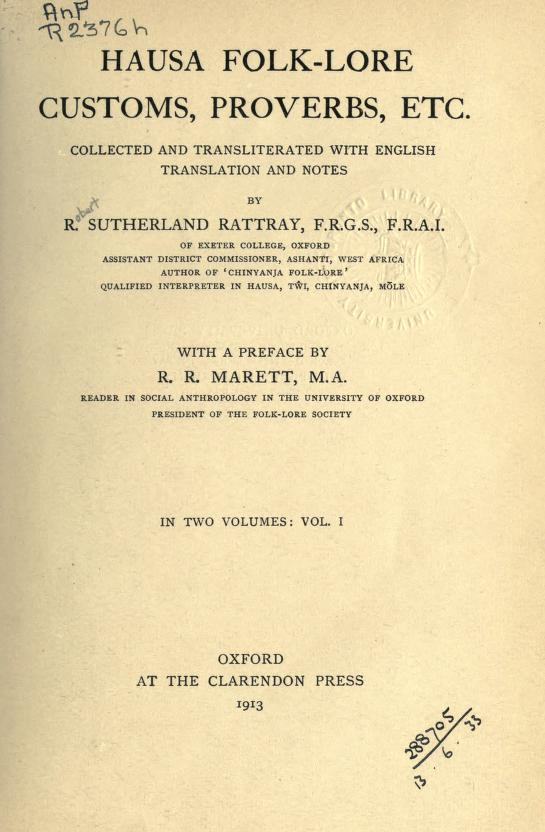

Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Details

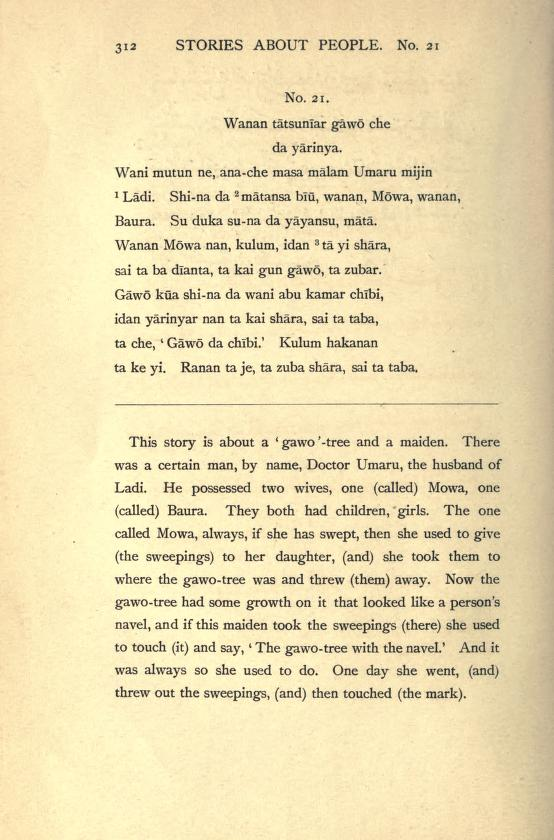

Robert Sutherland Rattray, "A Story about Three Youths All Skilled in Certain Things, and How They Used That Skill to Circumvent a Difficulty” in Hausa Folk-Lore: Customs, Proverbs, etc. Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes. Vol. 1, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913, 312–321.

Available Onllne

The Gaawoo-tree and the Maiden, and the First Person Who Ever Went Mad (accessed: July 28, 2021).

Genre

Folk tales

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

Cover retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 28, 2021).

Author of the Entry:

Chester Mbangchia, University of Yaoundé 1, mbangchia25@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Daniel A. Nkemleke, University of Yaoundé 1, nkemlekedan@yahoo.com

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Robert Sutherland Rattray

, 1881 - 1938

(Author)

Robert Sutherland Rattray (1881–1938) was born in India. He was a Scottish anthropologist and an authority on the native peoples of West Africa. He was educated at Exeter College at Oxford University and held a diploma in anthropology. In 1902 he entered Civil Service in Africa, first, in British Central Africa and from 1907, on the Gold Coast. During the Great War he served in Togoland and received the MBE, in 1929, he was progressed to CBE. In each place he was sent to, he studied local languages and conducted anthropological research about folklore, religion, beliefs, customs, law, art, folktales and proverbs. In 1924 he was made head of the Anthropological Department in Ashanti/Asante in acknowledgment of his merits. His contribution to the detailed study of the Ashanti customs and folklore was based on personal observations, contacts with the Ashanti, and a thorough knowledge and understanding of their culture. On his retirement, R. S. Rattray was a lecturer of anthropological topics at Oxford and elsewhere. He was passionate about flying, one of the first to fly to West Africa, a pioneer of gliding. He founded a club of gliding at Oxford and a week later was killed in a glider flying accident.

His main works include: Some Folk-Lore Stories and Songs in Chinyanja: with English Translations and Notes (1907), Hausa Folk-Lore, Customs, Proverbs, etc.: Collected and Transliterated with English Translation and Notes (1913), Ashanti Proverbs: the primitive ethics of a savage people: translated from the original with grammatical and anthropological notes (1916), An Elementary Mōle Grammar with a Vocabulary of Over 1000 Words for the Use of Officials in the Northern Territories of the Gold Coast (1918), Ashanti (1923), Ashanti Law and Constitution (1929), Akan-Ashanti Folk-tales (1930), The Tribes of the Ashanti Hinterland (1932), The Golden Stool of Ashanti: a Sacred Shrine Regarded as a Symbol of the Nation's Soul, and Never Lost or Surrendered, Its True History, a Romance of African Colonial Administration (1935).

Source:

“Captain R. S. Rattray, C. B. E.”, Nature 3577.141 (1938): 904, 929. (accessed: July 2, 2021).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolinska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Maalam Shaihu (Author)

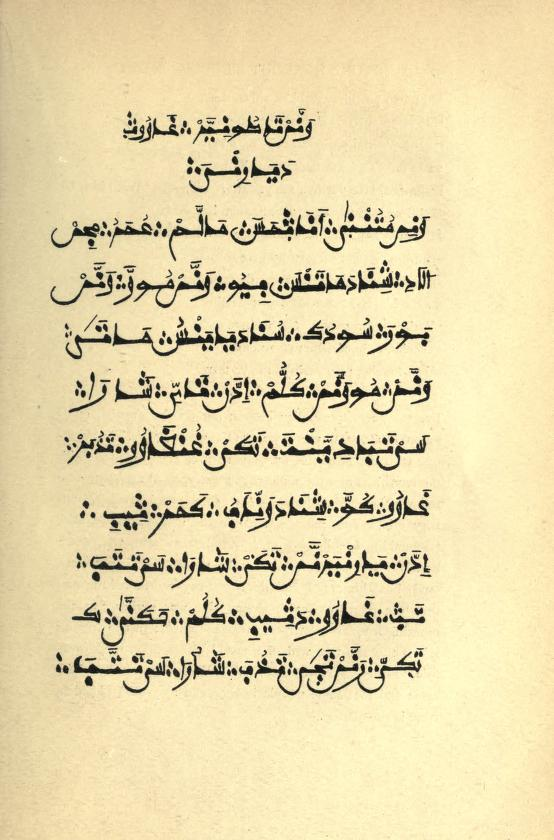

Maalam Shaihu (active in the early twentieth century) was one of the learned Hausas known as maalamai, who were the most respected and honoured members of the Hausa community in the Gold Coast and Nigeria. The use of Arabic corresponded at that time to the use of Latin in mediaeval Europe, the knowledge of Arabic was necessary for conducting any research about the Hausa culture. A maalam of the best class possessed all the language and literary skills and understanding of the Hausas. Thus, Shaihu cooperated with R. S. Rattray to gather Hausa stories and manuscripts and make the Hausa culture better known. Much of the work contained in Hausa Folk-Lore involved his translation from Arabic into Hausa, and Rattray’s translation into English from the Hausa. In 1907-1911 during Rattray’s journeys in West Africa and in England, Maalam Shaihu accumulated many hundreds of sheets of manuscripts. Thanks to his work the traditional lore lost nothing of its authenticity. It is worth mentioning that, by the grant of the government of the Gold Coast, Maalam Shaihu’s Arabic penmanship was preserved by facsimile reproduction of his Arabic text printed in the 1913 edition.

Source:

R. R. Marett, Preface; R. Sutherland Rattray, Author’s Note in R. S. Rattray, Hausa Folk-Lore, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Summary

A man named Umaru possessed two wives: Mowa and Baura, who both had girls. Mowa always swept the compound and gave her daughter the dirt to throw away, which she always did, where the gawo-tree was located. There was a part of the tree that looked like a human navel. This awakened the girl’s curiosity every time she went to throw dirt there. She would always stand there and say, "The gawo-tree with the navel." One day, she struck a mark on the tree, and it started following her. She ran until she encountered several individuals and asked for help, but it was in vain as the tree arrived and they could not help. Some people were sowing, and they promised to beat and kill whoever was following her; some people were hoeing, and they said they would lift their hoes to hit whoever was following her, and some people were silently ploughing. Lastly, she approached a lizard that promised to assist her if she would wed him. When the tree arrived, the maiden nestled close to the lizard. It told the tree that the maiden was stouter than it, but the tree insulted the lizard. The tree devoured the lizard four times; each time, the lizard came out of a different part of the tree’s body: eyes, ears, breast and navel. The gawo-tree died, and the lizard and the girl proceeded to their house. Once she was home, the girl started to do her household chores without explaining what had happened. When Umaru came out of the house and saw the lizard, the lizard explained everything. When they questioned the girl, she said, "May Allah save me from marrying a lizard." Her father called Buara and asked whether she would give her daughter in marriage, given that Mowa’s daughter rejected the lizard. She sent Umaru to the girl, and she accepted. Meanwhile, it transpired that the lizard was the chief’s son in disguise. When the chief received the news, he sent many slaves and properties to his son to give to Umaru and take his daughter away. The two lived contentedly. The lizard’s father had a slave called Albarka, a leper, and he went to Umaru’s house to seek his other daughter’s hand in marriage. When Mowa’s daughter saw him, she thought it was the chief’s son and accepted his proposal. The two went together and lived in the fields. One day, the lizard came for a visit, and Albarka came out and bowed to him, calling him master. Mowa’s daughter realised that had she married an undesirable person. She became depressed and frantic and was the first human to run into the bush.

Analysis

This myth represents the hidden relevance of disguise. It parallels the Ugandan proverb, “physical attributes do not guarantee a beautiful personality!” and the Egyptian proverb, "patience is the mother of a beautiful child.” The myth portrays the position of leper slaves in Africa and the world: people always have a phobia towards them, forgetting their worth. That is why Mowa’s daughter immediately rejects the lizard without knowing that he is disguised. Moreover, Mowa’s daughter’s downfall results from her mistaken social paring and trust. Just as the hunter in the South African myth, Gratitude: The Hunter and the Antelope*, who assists a crocodile and the crocodile plots to devour him. In both cases, the protagonists are shaken by their false judgements. Furthermore, the myth exposes bridal practice in West Africa: the groom’s family, like that of the chief in the myth, sends gifts to the brides’ family to ask for the bride’s hand in marriage. In such a case, the previous relationship between the two families, the nature of the gifts as differentiated by those offered by different suitors and the groom’s family’s social status determines the bride’s family’s acceptance or rejection. Lastly, the myth above is calm and entertaining while at the same time it expresses the importance of choices in life and their effects; appearance versus reality. The myth, thus, is relevant to young adults who, on their pilgrimages on earth, have to distinguish between outward beauty and internal beauty and know that gold can be hidden in garbage.

* Read more in Frobenius, Leo, and Douglas C. Fox, African Genesis: Folk Tales and Myths of Africa, Massachusetts: Courier Corporation, 1999.

Further Reading

Crump, Marty, Eye of Newt and Toe of Frog, Adder's Fork and Lizard's Leg: The Lore and Mythology of Amphibians and Reptiles, University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Addenda

Country of origin: Ghana

Although these myths were collected so many years ago, they are still being told to children and young adults in traditional African communities. And like all other oral narratives, several versions of the same story may be available in different places.

The first edition of Hausa Folk-Lore was published in English by Oxford Clarendon Press, providing, however, the text of the stories in three languages simultaneously: Hausa, English and Arabic as it was an academic publication aimed at anthropologists, students and Hausa language learners (especially that it contains pronunciation tables at the beginning, and some notes with vocabulary and grammar at the end of vol. 2).

Even though Rattray aimed his book at students of the Hausa language and anthropologists, after his death it was republished many times without Hausa and Arabic text as the interesting Hausa stories to be told, while the oral versions of the folk tales were still alive. It shows two parallel ways of the reception of these folktales and this is a phenomenon which is worth being highlighted.

Scans retrieved from Internet Archive (accessed: July 28, 2021).