Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

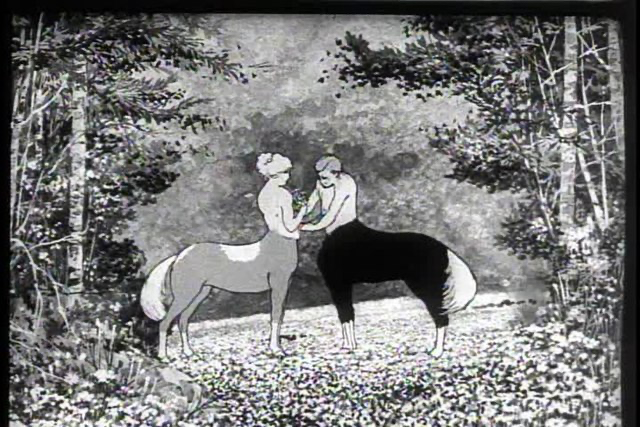

The Centaurs [fragments]. Created by Winsor McCay. 1921. The Centaurs survived only in fragments; there is not much information about the clip or the story behind the production (Canemaker 2005: 197-198). In 1921 McCay’s works were overshadowed by big comp

Running time

Available Onllne

en.wikipedia.org (accessed: August 17, 2018).

Genre

Animated films

Black and white films*

Mythological fiction

Short films

Silent films

Target Audience

Children

Cover

The footage from Winsor McCay's animated film. Retrieved from Wikipedia, public domain (accessed: July 4, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, mauril68@gmail.com

Portrait of Winsor McCay, photographed by Crobot (17 February, 1907), the file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike (accessed: May 25, 2018).

Winsor McCay

, ca 1867/71 - 1934

(Animator)

(Zenas) Winsor McCay was a Canadian cartoonist and animator, perceived as being “far ahead of his time” (Furniss, 2017, p. 40). It might be claimed though that his works were too “artistic” or “demanding” for his times: the animation industry in the 1910s and 1920s was developing fast and needed something more than his so called “personality animations” or the kind of art that McCay produced. He started as a cartoonist and author of many comic strips in various newspapers and magazines, which made him a celebrity (Furniss, 2017, p. 41). Then he became an animator (his first animation: Little Nemo was released in 1911); later on he suffered a similar fate to e. g. Georges Méliès, as they both “fell into relative obscurity as cinema moved into the late silent era” (Furniss 2017, p. 43).

He is best-known for animations like: Little Nemo (1911) or Gertie the Dinosaur (1914). His later works, such as The Sinking of the Lusitania, were produced in reaction to the conflicts of World War I. The present entry describes The Centaurs from 1921.

Bio prepared by Anna Mik, University of Warsaw, anna.m.mik@gmail.com

Summary

The 2:25 minute long animation tells the story of an idyllic life of a centaurs’ family. In the first scene we meet a female centaur – or centauride – with bare breasts, who appears from behind the bushes. At first we do not see her whole figure – the lower, equine part appears a few seconds later, as the upper, human torso introduces the character. In the next take we see an elder female centaur with glasses on, contrasting with the young woman’s body. The young centauride picks flowers and enjoys the beautiful sunny day, when another contradictory image is presented: a young centaur appears and kills a flying bird with a stone – apparently for no reason at all. Then he looks for the centauride, (possibly) calls her, and meets her on the meadow. The next scene brings two elderly centaurs (probably the parents of the young centaur): the old centaur leans on a rock and holds on to the old centauride (from the previous scene), as if they were about to fall. Then the young centaur approaches and introduces them to his partner. She is welcomed to the family with hugs. The scene closes with the appearance of a child-centaur, who he is playing and showing off in front of his parents and grandparents. The smiling face of the child-centaur enclosed in a heart shaped frame ends the animation.

Analysis

It is hard to determine whether this animation was made for young viewers. It is clearly an artistic attempt to present the myth to a rather small audience, not to the masses (Furniss 2017, p. 43). If we recall the Pastoral Symphony episode from Disney’s Fantasia (vide the entry Fantasia [the Pastoral Symphony episode], we might discern different strategies in presenting the myth via animation. Almost all centaurides there wear bras, while in The Centaurs they wear nothing (just like in the “original” myth). Because sexuality is often hidden from the young (not always with justification), we might assume that this piece has been designed for adult members of the audience. Animation is less lively, subtle, story develops at a slower pace, also violence (killing the bird) is present, which would definitely not appear in a Disney production. The picture is not as “attractive” as Fantasia, not as “appealing,” as colorful and dynamic.

However the animation may still be relevant to children’s culture. As Furniss states, back then animation industry was a “fluid institution” and “partnerships were formed to keep up with the rapidly growing needs” (Furniss 2017, p. 39), and we know that McCay and Disney knew each other (Disney paid a tribute to McCay in the Disneyland episode: “The Story of Animated Drawing”). The two artists may have had been similar in many respects, inter alia in the matter of perceiving womanhood and its diversity in the world of American culture, as they their work clearly shows.

Another link to children’s culture is the appearance of a child-centaur, which is not very common. It is interesting how the boy’s playful nature is expressed by both parts of his hybrid body: human corpus and equine legs. He is full of life, energy and easiness. His character might be treated as an example of the Rousseau’s child who is not troubled by the problems of the outside world. It also suits the mythical, idyllic setting, where no harm could come to anyone and all can live in the everlasting Arcadia (which also connects this animation to The Pastoral Symphony mentioned before).

The ending sequence of the animation (child’s face in a heart-shaped frame) puts emphasis on his character, as at the end he is in the center of Arcadia, the source of life and happiness.

Further Reading

Theoi Project © Copyright 2000–2017 Aaron J. Atsma, Netherlands & New Zealand, Mythic Bestiary, II. Monsters & Creatures of Myth, Centaurs at theoi.com (accessed: August 17, 2018).

Canemaker, John, Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2005 (ed. pr. 1987).

Furniss, Maureen, Animation. The Global History, London: Thames & Hudson, 2017.

Vadeboncoeur, Jim Jr., “The Golden Era of Pen & Ink Illustrations 1890–1922”, Black & White Images 2 (2004).

Vadeboncoeur, Jim Jr., “The Golden Era of Pen & Ink Illustrations 1890–1922”, Black & White Images 4 (2008).

Vadeboncoeur, Jim Jr., Winsor McCay, bpib.com (accessed: August 17, 2018).

Addenda

The presence of mythical creatures, centaurs and centaurides (Theoi, passage: centaur). No clear individual identification, members of the centaur family (grandparents, parents and a child) do not have names, they do not speak which is normal in a silent movie but no explanatory texts of any kind appear in the existing fragments.