Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Evi Pini & Kalliopi Kyrdi, Η Αριάδνη αφηγείται ιστορίες από την κυκλαδική εποχή στο Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο [Ī Ariádnī afīgeítai istoríes apó tīn kykladikī́ epochī́ sto Ethnikó Archaiologikó Mouseío], Short Museum Guides [Μικροί Οδηγοί Μουσείων (Mikroí Odīgoí Mouseíon)] (Series). Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 32 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Illustrated works

Instructional and educational works

Target Audience

Children (6+)

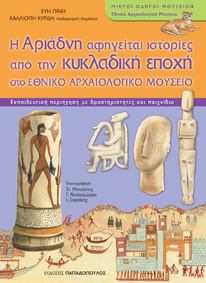

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher. Retrieved from epbooks.gr (accessed: July 5, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Kalliope Kyrdi (Author)

Kalliope Kyrdi studied Law and Pedagogy at the University of Athens, and has worked in primary school education. Kyrdi has been responsible for cultural matters in the 1st Directorate of Primary Education, Athens, since 2007.

Source:

Profile at the epbooks.gr (accessed: June 27, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Evi Pini (Author)

Athens-born Evi Pini studied Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Pini has been working for the Greek Ministry of Culture since 1990, specialising in children’s educational programmes.

Sources:

Information about the Author, see here (accessed: June 26, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

The first part of the book (pages 4 to 8), which is entitled “a first familiarisation with the Cycladic civilization”, presents the geographical, chronological, and social setting of Cycladic communities. Rare words, such as βραχονησίδα, μεταλλείο, and οψιανός (“rocky islets”, “mines”, and “obsidian”), are explained in dedicated boxes (page 4). An emphasis on materials accounts for what the Bronze Age (3300–1100 BC) and the Cycladic period within it (3200–1100 BC) stand for (page 5). An evolutionary narrative is offered for human activity. At first, the Cycladic people lived in hamlets, worked the land, and kept animals. Later on, people engaged in maritime trade. There was progress also in terms of the ancients’ ability to construct boats. Technical advances enabled distant travel. People became prosperous and more numerous, and their settlements turned into rich towns with busy ports.

These developments are reflected in a fresco from the island of Thera, which shows a densely populated seaside town with multi-storey buildings.

In the second and main part of the book (pages 9 to 20), we encounter a cat called Ariadne, our museum guide. Ariadne tells us that she was born in the Cyclades, on the island of Naxos. The archaeologists who excavated on the island gave her the name “Ariadne”, because the cat reminded them of the Cretan princess that Theseus had abandoned at Naxos. Our talking animal provides details about find spots and asks children to observe exhibits carefully (page 10). Artefacts are grouped based on material – marble, clay, and metal – and there is discussion about their uses and artistic qualities.

The final section of the book (pp. 21–32) offers interactive activities for children, answers to the questions in the previous pages, a bibliography, and detailed captions for all illustrations. The experience of a museum visit continues at home and in the classroom.

Analysis

Of particular interest here is the extent to which a museum guide about a prehistoric period refers to myths and traditions, Homeric or other. On the whole, there is little reference to mythology. Instead, the main emphasis is on art and archaeology.

On the front cover, we see Cycladic figurines as well as a fresco and a fragmentary piece of figured pottery. Indeed, this book is exceptionally rich, covering diverse classes of Cycladic artefacts, beyond the marble figurines that the general public tends to associate with the prehistoric art of the Cyclades.

Like other guides in the series, the authors’ primary audience is young children, who are asked to write down their name, the date of their visit, and whom they visited the museum with. This book is also about an adult audience, parents, teachers, museum educators, and other guardians of young learners. The authors are to be commended for providing background information in an introductory page and throughout the book to help adults prepare for the museum visit and answer children’s questions. The main object here is to educate all readers.

The book is about a visit to the largest museum in the country, as we read on page 3.

Yet, there are no allusions anywhere in the book to national identity. Readers are not made to feel proud of the Cycladic heritage. For example, we read on page 4, about a great ancient civilization, and not about a Greek civilization. The people in the reconstructed drawings do not have ethnic Greek or south-Mediterranean features, but characteristics inspired by art. There is emotional detachment and objectivity in the text and images. The use of terms such as “the Cycladites” and “the Minoans”, however, may have connotations for ethnic groups.

The name chosen for the cat is an ingenious way to connect the past with the present, namely, mythology with archaeological practice. Also evident is the archaeologists’ care for pets, as Ariadne was taken back to the museum in Athens. An information box (p. 9) recounts how the mythological Ariadne helped Theseus on Crete, and that the hero promised to take her back to Athens. Theseus, nonetheless, left Ariadne sleeping on a beach at Naxos and departed for Athens on his own. Children may think that Theseus back then was hard-hearted, contrasting with the archaeologists’ care for the cat in recent times. In all likelihood, the children will form a link between the past and the present, perhaps not differentiating between the two. Mythology, thus, enters daily life, that is, the experience of visiting the museum, even though Ariadne of Minoan Crete may have little to do with Cycladic antiquities.

There are explicit references to gender. A sizeable figurine, measuring 1.45 m in height, is described as “a large marble lady” (p. 11) and two figurines of musicians, both from the island of Keros, are introduced as “two famous gentlemen” (p. 12). Cycladic artists’ conventions point to differences between males and females. In studying Theran frescoes, children are prompted to think about the brown skin tones of the two male young boxers and about the women’s white faces.

Contemporary gender stereotypes for the division of labour could make the distant and exotic past of Cycladic times more accessible to readers. In an illustration showing a reconstruction of a workshop (p. 15) all people are male and half naked, resembling the males on a ceramic stand from Melos featuring fishermen (front cover and p. 14). Other illustrations depict women, and not men, grinding cereal and cooking, although there exist, to my knowledge, no representations of women performing these tasks in Cycladic art.

Further Reading

Information about the book at www.epbooks.gr, published January 10, 2009 (accessed: July 27, 2018).

Addenda

Evi Pini & Kalliopi Kyrdi, Η Αριάδνη αφηγείται ιστορίες από την κυκλαδική εποχή στο Εθνικό Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο. [Ariadne tells stories from the Cycladic period in the National Archaeological Museum]. Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2009, 32 pp.

The book forms part of a series of 6 Short Museum Guides that appeared in print from 2008 to 2010.