Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

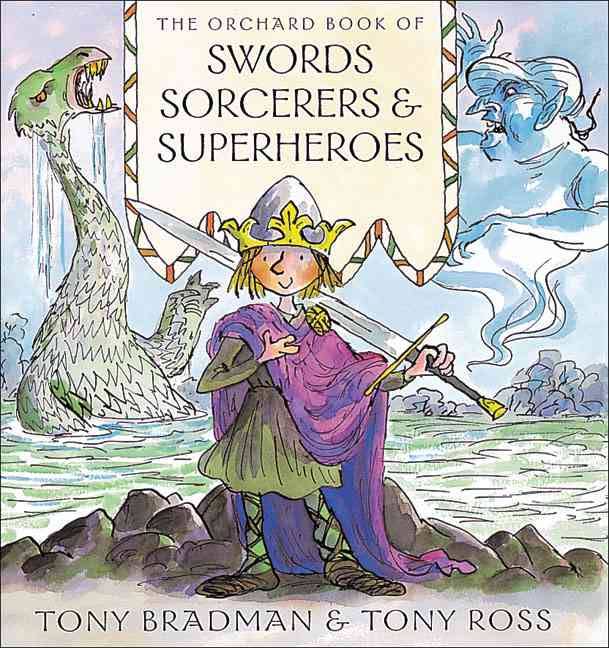

Tony Bradman, The Orchard Book of Swords Sorcerers and Superheroes. London: Orchard Books, a division of Hachette Children's Books, 2003, 128 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Fables

Folk tales

Myths

Picture books

Short stories

Target Audience

Children (7–13)

Cover

Courtesy of Hachette Children's Books.

Author of the Entry:

Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author

Tony Bradman

, b. 1954

(Author)

Tony Bradman is a British born author of children’s books and short fiction pieces. He was born in London and still lives there. He cites The Hobbit and the novels of Rosemary Sutcliffe as early influences on his love of reading (see here, accessed: July 4, 2018). After studying at Cambridge University he became a journalist, eventually writing reviews of children's literature for a magazine called Parents. He has been a children's author since the 1980s, and is arguably best known for his long-lasting series about Dilly the Dinosaur (1986–1994), which sold over two million copies globally. He earned renown for this series. His historical titles include Spartacus (with Tom Bradman), The Story of Boudicca, and Harald Hardnut and he has published a considerable number of retellings of traditional myths and legends.

He has published over seventy stand-alone books and four popular series. His work has been published by Methuen Publishing, Aldred A. Knopf, Puffin Books and Harper Collins.

Before dedicating his time fully to writing children’s literature in 1984, Bradman worked as a music writer and reviewer of children’s books.

Sources:

Official website (accessed: October 10, 2018)

Profile at the wikipedia.org (accessed: October 10, 2018)

Profile at the walker.co.uk (accessed: October 10, 2018)

Profile at the penguin.co.uk (accessed: October 10, 2018)

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk and Tikva Schein, Bar-Ilan University, tikva.blaukopf@gmail.com

Questionnaire

1. What drew you to writing / working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

I’ve always enjoyed the myths and legends of the Greeks, and have re-told quite a few. They’re great stories, and the main challenges are in getting the level right for younger children – and also dealing with some of the more extreme violence! There’s lots of gory stuff in the myths, and you need some jeopardy to generate suspense, but you have to be careful most to go too far.

2. Why do you think classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

The great myths and legends have lasted because they’re great stories, and they tell us a lot about what it means to be human. They’re stories about young characters facing overwhelming odds (Theseus and Jason), tales of betrayal and revenge (Electra and Medea). Even Hercules is more than just a hero… The stories are also embedded in European culture and the cultures of countries settled or influenced by Europeans…

3. Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University)? What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I did study Latin and Greek at school, and have tried to improve my skills in both languages. I read some of the original texts, but also good translations. For background I surfed the web – lots of websites (some good, lots not very good at all) – Wikipedia is always useful!

4. Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers, esp. in (insert relevant country)? How concerned were you with “accuracy” or “fidelity” to the original? (another way of saying that might be – that I think writers are often more “faithful” to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail – is this something you thought about?)

For children it’s really a case of being “faithful” to the original – the originals are quite hard and violent, and can also be confusing. I’m very keen to re-tell the myths in a contemporary way, with lots of action and suspense and good characters and dialogue. And because the tales are so rich, that’s easier than it sounds.

5. Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

I’m writing a lot of historical fiction these days – I’m currently working on a story about the revolt of Boudica against the Romans in Britain – and I’ve always wanted to write the story with Telemachus as the central character.

Prepared by Tikva Schein, Bar-Ilan University, tikva.blaukopf@gmail.com

Tony Ross

, b. 1938

(Illustrator)

Tony Ross was born in 1938 in London. He worked as a cartoonist, a graphic designer, as the Art Director of an advertising agency, and as Senior Lecturer in Art at Manchester Polytechnic after studying at the Liverpool School of Art. Ross is an illustrator of both his own (e.g. Goldilocks and the Three Bears from 1976) and other authors’ books. He has won 10 awards for his art and has worked on 43 books. Tony has illustrated over 800 books, including the wildly successful Horrible Henry series. Currently he lives in Cheshire in England. Tony likes to experiment with his art.

Sources:

Profile at the literature.britishcouncil.org (accessed: April 12, 2018).

Profile at the theguardian.com (accessed: April 12, 2018).

Profile at the us.macmillan.com (accessed: April 12, 2018).

Profile at the Harper Collins Publishers website (accessed: January 17, 2018).

horridhenry.co.uk (accessed: September 1, 2017).

There is also an interview available on YouTube (accessed: April 12, 2018).

Bio prepared by Allison Rosenblum, Bar-Ilan University, allie.rose89@gmail.com and Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk and Agnieszka Maciejewska, University of Warsaw, agnieszka.maciejewska@student.uw.edu.pl

Summary

- Chapter 1. Voyage to the Edge of the World. The Story of Jason and the Golden Fleece.

- Chapter 2. The Magical Sword. The Story of King Arthur.

- Chapter 3. The Fabulous Genie. The Story of Aladdin and his Magical Lamp.

- Chapter 4. An Apple for Freedom. The Story of William Tell.

- Chapter 5. Superhero. The Story of Hercules and the Monstrous Cacus.

- Chapter 6. The Fantastic Voyage of Sinbad. The Story of Sinbad the Sailor and The Roc.

- Chapter 7. The Fearsome Dragon from the Lake. The Story of George and the Dragon.

- Chapter 8. Open Sesame! The Story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

- Chapter 9. The Man-Eating Monster. The Story of Theseus and the Minotaur.

- Chapter 10. The Silver Arrow. The Story of Robin Hood and the Sheriff.

Analysis

This work is heavily illustrated and visually appealing, so that no double-page goes without an illustration and most pages contain at least one. The characters in the illustrations wear clothing that reflects the culture and period of the stories they appear in. In the Greek stories this takes the form of belted tunics, sandals, and plumed helmets for soldiers and guards. The women in the stories wear make-up and hair-styles that demonstrate an Egyptian or Eastern influence although they are Greek (Ariadne) and Colchian (Medea). Several of the male characters are depicted with long dark hair, and the illustrations follow the ancient pattern of depicting young men as beardless and older men bearded. As the stories are presented out of chronological order, the use of distinctive clothing and equipment (swords, ships, thrones, architecture etc.) reminds the reader that the stories take place in specific contexts; in the case of the Greek stories, this emphasises a pre-industrial (specifically, ancient), mountainous, eastern environment with a hot climate. The stories include a lot of direct speech and flow in a lively manner.

Voyage to the Edge of the World. The Story of Jason and the Golden Fleece is a straight-up retelling of the traditional myth (as found in e.g. Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica), beginning with Jason's birth and ending with the Argo heading back to Greece after a successful mission. The Argonauts are not individually named, but their masculinity is emphasised by repeated reference to them as a 'band of brothers', echoing Shakespeare's Agincourt speech (Henry V, 4.3.60).

The episode of King Phineas and the Harpies is included, with the Harpies depicted as bats. The section with Medea's decision to help Jason explicitly addresses the betrayal of her father: 'She loved her father, but as soon as she had seen Jason, she knew that she loved him more'.The soldiers who sprout from the earth are statue-like eastern warriors, more akin to the earth-born men of Apollonius' Argonautica than the frequently used Clash of the Titans (1981) skeletons. Medea herself drugs the fleece-guarding dragon, but it wakes in time to prevent Aeetes and his retinue from halting Jason and Medea's escape. The story concludes with Jason's happiness to be returning to banish Pelias with the fleece, Medea, and the Argonauts.

Superhero. The Story of Hercules and the Monstrous Cacus. With 'Superhero', the title of this story explicitly connects Hercules to the modern tradition of superheroes with special powers and an inclination to fight injustice and baddies, a connection that is then born out in the choice of Hercules story – Hercules slaying a terrorising monster. The tale begins with Hercules already a young man, 'a strapping, muscular youth wearing the pelt of a lion.' The reader then learns that Hercules has had a difficult time recently, forced to complete twelve tasks as a 'slave' to Eurystheus because the gods are 'jealous' of him. The issue of slavery perhaps draws on the tradition in which Hercules was enslaved to Queen Omphale for a year (Apollodorus, Library, 1.9.19; 2.6.3; Sophocles, Women of Trachis, 253ff) as the labours are not traditionally presented as slavery, although it may simply have been a way of expressing the compulsion that he was under, as there is no mention of the tradition of Hercules performing the labours as atonement for slaying his family – which was perhaps deemed unsuitable for a young audience. As such, Hercules presents a very straightforwardly sympathetic figure, and the injustice he has faced aligns him with much of the modern tradition around superheroes. There is an illustration of Hercules fighting Geryon, opposite one of a hideous Cacus emerging from his cave. When villagers prove unwilling to give Hercules information, he loses his temper, kicks in a front door and holds up a stammering man by his tunic, in an episode accompanied by a large illustration. This is a curious incident to have included, as it lacks ancient precedent (the usual explanation for including harsh behaviour), and the bullying behaviour appears without any cautionary moral or connection to Hercules' other problematic violent episodes. Hercules defeats the gloating Cacus using his great strength. On behalf of his village, the bullied villager then asks Hercules to be their king, but he declines. Hercules and the reader then learn that this 'scruffy, smelly, run-down place' is Rome (for Heracles removing Cacus from early Rome, see Vergil, Aeneid, 8.190–279; Livy 1.7.3–15; Ovid, Fasti, 1.543–86). Hercules smiles (knowingly?) and predicts that Rome will become great now Cacus has gone. The story concludes with confirmation that Hercules completed his labours, and that he was remembered in Rome, which did indeed become great. The story thereby acts as a foundation tale for Rome and emphasises the active effectiveness of Hercules' strength and aggression.

At the opening of The Man-Eating Monster. The Story of Theseus and the Minotaur, Aegeus tries to prevent Theseus from going to Crete, before eventually conceding, establishing Theseus' bravery and determination, and arguably the superiority of the younger generation to the older. Once on Crete, Ariadne admires Theseus' 'pride and bravery'. In a foreshadowing of her later actions, the reader learns that Ariadne 'was afraid of her father, and hated him too.'

When it comes to the Theseus–Ariadne negotiation, Ariadne appears pushy and Theseus is immediately unsure: "Just that you take me with you", said Ariadne. "Oh... and marry me." Theseus 'didn't like the idea very much', but decides to leave that issue until after the Minotaur has been beaten; he crosses his fingers behind his back as he makes his promise to her. Ariadne takes Theseus to the labyrinth herself without the other companions. She provides a sword and 'magic' thread that leads the way to the Minotaur as well as revealing the way back out.

The Minotaur is depicted looming above Theseus above the title page, and then again in a full-page illustration at this stage in the story. In this second image, the Minotaur lies prone upon his back as Theseus plunges the sword joyously into his chest. The Minotaur's white (not, as sometimes, red) eyes bulge with fright, and his mouth is open in a scream, revealing huge yellow wolf-like fangs. He wears no clothing, but has 'rough hide' about his waist, in contrast to the yellowy-brown flesh of his arms, chest, and lower legs. As such, the Minotaur is very beastly, and depicted in a manner that renders him pathetic rather than sympathetic.

Ariadne helps Theseus and his companions escape the island, but she is then dismissed from the story rather ruthlessly. Theseus has less and less desire to marry her; he forgets that she helped him: 'After all, what kind of girl is it who knows how to make sleeping potions and is happy to betray her own father?' The reader is told that Ariadne was abandoned, and is offered three possible explanations of what happened to her: that she died, returned to Crete, or married a god. The options about Ariadne's fate reflect alternative ancient traditions, but leaving it uncertain gives the impression of indifference as this is the first time that such uncertainty has been introduced to the story-telling. The scathing 'what kind of girl...' remarks are perhaps intended to reflect Theseus' self-justifying thought-process, but this is not made clear, particularly as this would be the first time that a hero's thoughts have been conveyed in this way. The result of this is that many readers, the young target audience in particular, are likely to take the comments about Ariadne at face value. As such, this aspect of the story creates an overall hostile impression of a rare female character, and the reader is not prompted to reflect critically on Theseus' decision to betray the person who helped him. This endorsement of Theseus' actions is also reflected in the ending of the story which, while noting that Theseus 'betrayed' his father by forgetting to change the sail, assures the reader that Athens is better off now. Rather unusually, the final illustration of the story depicts a tiny figure of Aegeus throwing himself off a cliff.

This is essentially a simple retelling of the traditional myth (for which see e.g. Plutarch, Theseus; Apollodorus, Epitome; Apollodorus, Library, book 3; Diodorus of Sicily, Library, book 4; Ovid, Metamorphoses, 8.155–182), yet the arrangement of the story produces a specific effect. The narrative arc runs as 'young man kills monster thus helping his people'. Although the more complex elements are there (Ariadne betrayed; Aegeus' suicide), they are supressed to a greater extent than is usual in a retelling of this length, reducing the moral complexity that is available to retellings of this myth.

The three Greek stories included here all follow the pattern of young-man-kills-monster, associating Greek myth with the fantastic and with the coming-of-age/adventure narrative. Only one of the other stories features this monster-killing pattern, which therefore underlines the idea that this is something prominent in Greek myth. The young men in the Greek myths achieve their goals for the most part through bravery, intrepidness, and strength; again, this differs somewhat from the other stories, where guile proves more important. All of the protagonists in these stories are male, heavily associating 'sword, sorcerers, and superhero' adventures with boys and men. Female characters feature more prominently in the Greek group than in any of the other myth groupings, acting as helpers in two of the three stories, so while in one story the female character is treated as an object of suspicion, the overall impression is that mythical Greece is not a hyper-masculine, male-only environment. The book's gorgeous and informal illustrations add a light touch and humour to the collection.

Further Reading

Blanshard, Alastair, Hercules, a Heroic Life, London: Granta Books, 2006.

Phillips III, C. Robert, 'Cacus', in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd ed. 2003, 267.

Small, Jocelyn Penny, Cacus and Marsyas in Etrusco-Roman Legend, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982.

Stafford, Emma, Herakles, London: Routledge, 2012.

Webster, T.B.L., "The Myth of Ariadne from Homer to Catullus", Greece & Rome 13.1, 1966, 22–31.

Copyrights

1) This permission is granted on the understanding that the database is organised on a non-commercial, non-profit basis. If anything changes, you must let us know straightaway.

2) Full acknowledgements will be made to the title, author and illustrator of each book, plus the wording: 'reproduced by permission of (imprint - in these cases, 'Orchard Books'), the Hachette Children's Group, Carmelite House, 50 Victoria Embankment, London EC4Y 0DZ.'

3) The covers are reproduced unaltered.

4) All rights other than inclusion of the covers in the database are reserved to Hachette Children's Group.