Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Kenneth Grahame, The Wind in the Willows. London: Methuen & Company, 1908, 262 pp.

Available Onllne

www.gutenberg.org (accessed: December 30, 2020)

The Wind in the Willows, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908, at archive.org (accessed: September 30, 2022).

The Wind in the Willows, ill. Paul Bransom, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1913, at archive.org (accessed: September 30, 2022).

Genre

Children’s novel*

Fantasy fiction

Target Audience

Crossover (Children)

Cover

Cover of the Scribner's Sons edition from 1913 designed by Paul Bransom. Retrieved from Archive.org (accessed: September 30, 2022), public domain.

Cover of the New American Library edition (1969) by Thomas Cizauskas. Retrieved from flickr.com, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 (accessed: February 2, 2022).

Author of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Kenneth Grahame ca 1910. Retrieved from Wikipedia, public domain (accessed: February 2, 2022).

Kenneth Grahame

, 1859 - 1932

(Author)

Kenneth Grahame was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. His mother died of puerperal fever when he was five, and his father sent him and his siblings to be cared for by their grandmother, in the village of Cookham, in Berkshire, England. He and his sister and brothers grew up in an idyllic rural setting, near the River Thames, where an uncle introduced them to boating. At the age of 20, Grahame was sent to work in the Bank of England, where he was promoted through the ranks, becoming Secretary. He retired in 1908, owing to ill health. He married Elspeth Thomson in 1899, and they had a child, a boy named Alastair. Grahame told Alastair bedtime stories, which he later turned into his best-known work, The Wind in the Willows (1908). Alastair, partially blind, frail and quirky, struggled to fit in with his peers, and died of suicide at the age of twenty. Grahame’s writing career includes stories published in London periodicals, collected as Pagan Papers (1893), The Golden Age (1895) and Dream Days (1898). He died in 1938, in Pangbourne, Berkshire.

Sources:

Lyndall Gordon, Dark-hearted dreamer: the double life of Kenneth Grahame, newstatesman.com, published November 7, 2018 (accessed: December 30, 2020).

en.wikipedia.org (accessed: December 30, 2020).

britannica.com (accessed: December 30, 2020).

Bio prepared by Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Adaptations

The Wind in the Willows has been adapted into several stage plays, theatrical films, and television and radio series, including:

Toad of Toad Hall (stage play, 1929, by A. A. Milne);

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad (1949, animation, Walt Disney);

Wind in the Willows (Broadway musical, 1985, by Roger McGough (lyrics), William P. Perry (music), Jane Iredale (book));

The Wind in the Willows (live-action film, 1996, dir. Terry Jones);

The Wind in the Willows (stage play, 1991, by Alan Bennet),;

The Wind in the Willows (live-action tv film, 2006, dir. Rachel Talalay);

The Wind in the Willows (children’s opera, 2021, Elena Kats-Chernin (music), Jens Luckwaldt (libretto)).

For a full list see here (accessed: December 30, 2020).

Translation

The Wind in the Willows has been translated into at least 45 languages.

Summary

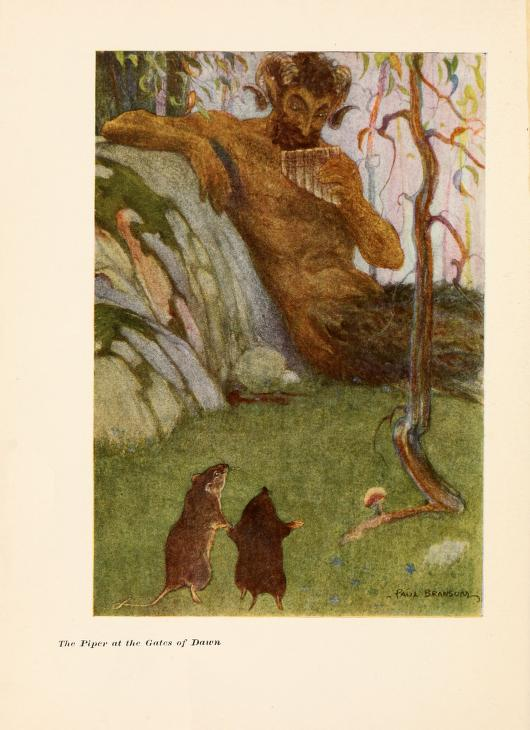

The story of Mole, Ratty, Toad, and Badger and their lives in and around an English river. Mole wakes one morning, aroused by the feeling of Spring in the air, and sets out into the wide world. There, he meets Ratty, a river rat, who invites him to join in a boating picnic. From there, it is a short jump to meeting Toad, a lively and affluent creature who lives at Toad Hall, and who careens through the landscape with careless abandon, much to the annoyance of Badger, old and crusty. Most of the main narrative concerns the adventures and misadventures of Toad, with individual chapters given over to Mole and Ratty when they are called to their own adventures: Mole getting lost in the Wild Woods in a snowstorm en route to visiting Badger; Ratty being drawn to adventuring on the ocean when he meets the Sea Rat. Toad’s adventures centre on fast forms of transport – a caravan, a car, a train, and lead him into trouble: he is arrested for speeding, and escapes jail by dressing as a washerwoman. Returning home to Toad Hall, he discovers his estate has been taken over by thieving animals such as stoats and ferrets, but with the help of Mole, Ratty and Badger, the interlopers are routed, and Toad is restored to his home. Many feasts and parties feature in this charming story, which depicts the English landscape as an idyllic Arcadia, one where the influence of Pan is never far from the surface: indeed, in the chapter, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Mole and Ratty meet the god himself when they set out at night to rescue Portly Otter, the young son of their friend. They find the baby otter curled up at the feet of Pan, sleeping, and in the morning remember only a sense of general awe and amazement. Other classical elements include Roman ruins in the Wild Wood, where Badger lives, and the presentation of Toad’s adventures as a kind of amphibian Odyssey - a journey away from home and back again.

Analysis

This famous children’s book, written by Kenneth Grahame for his young son, features a light classicism throughout: the mention of Roman ruins helps anchor that sense in a historical reality, and underscores the pastoral qualities of the novel. Throughout, Grahame exploits this sense of the pastoral as ideal for children’s stories: focusing on small, harmless animals, and giving a sense of idyllic nature, with an orderly progression of seasons, featuring delicious seasonal meals, and friendship throughout. In this, Grahame may be influenced by the odes of Horace, and Virgil’s Eclogues and Georgics, which emphasize the idea of the pastoral landscape as a place for friendship, feasting and song.

Grahame uses this approach in an earlier children’s book: The Olympians, a series of stories about five orphaned children living in a house in the country with irritating uncles and aunts. The children enjoy the pastoral idyll of childhood, but refer to their guardians sardonically as "Olympians," meaning powerful but remote beings who command rather than consult. The association of childhood with the pastoral is a common one (see for instance, William Wordsworth or William Blake), but it is particularly dominant in early 20th-century children’s literature, which is marked by a classicism intended to overturn or challenge late-Victorian mores. Grahame, Edith Nesbit, J. M. Barrie and other writers all employ the image of the pastoral to present childhood as a kind of Arcadia, removed from ordinary space and time, a kind of golden age, swiftly over but immeasurably precious.

Although The Wind in the Willows does not feature children, its emphasis on the adventures of animals is intended to appeal to children: these animals are anthropomorphic in that they own property, wear clothes, and operate machinery; they are also not children (with the exception of Portly Otter). Nevertheless, their anthropomorphism combines with a kind of animalistic set of drives that make their characters distinct (Mole is vague and dreamy; Ratty is cunning and clever; Badger is grumpy but good hearted; Toad is erratic and ebullient), and cause drama. Because they are animals, Ratty and Mole are able to see and recognize the great god, Pan; because they are adults, they forget their meeting with him the next morning.

The presence of Pan in the novel is as a pastoral god who presides over the animal world, especially the world of children – it is striking that he takes care of the lost baby Otter, who sleeps confidingly at his feet. It is also striking that he is far removed from the world of machinery and cities, a world that initially has allure for Toad (until he is frightened back to the pastoral). Overall, then, The Wind in the Willows offers readers a combination of traditional pastoral elements with reflections on the modern world (a tension that is also common in Classical pastoral literature).

The Roman ruins, where Badger lives, remind the reader that Britain was once colonized by the Romans, and that the land is layered with remnants of different human civilisations. That the Roman building (presumably a villa) lies in ruins and is inhabited by wild animals is also a reminder that human time and animal time run differently, and that animals live their lives around humans. The motif of the Roman past is common in British literature, from the Anglo Saxon poem The Ruin (8th or 9th century) which contrasts the ruins of a Roman city with its imagined vibrant past, to contemporary novels, such as Joan Aiken’s The Shadow Guests, in which ghosts from the ancient past have impact on present day children. Historical time contrasts with children’s and animals’ sense of time, in which time passes less in a linear manner, and more in a form of mythical, cyclical movement: this sense confirms an adult nostalgia for childhood, in which the child’s ability to live in the moment is combined with adult regret that one has to grow up at all, and contrasted with the pressures of adult life.

Further Reading

Hale Elizabeth, “Truth and Claw: The Beastly Children and Childlike Beasts of Saki, Beatrix Potter, and Kenneth Grahame”, in A. E. Gavin and A. F. Humphries, eds., Childhood in Edwardian Fiction, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2009, 191–207.

Hale, Elizabeth, "Classics, Children’s Literature, and the Character of Childhood, from Tom Brown’s Schooldays to The Enchanted Castle", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature. Brill, Leiden, 2015, 15–29.

Harris-McCoy, Daniel E., ""On the Chance": An Allusion to Vergil's Aeneid in Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows", The Classical World 106.1 (2012): 91–95. Web.

McCooey, David, and Emma Hayes, "The Liminal Poetics of The Wind in the Willows", Children's Literature (Storrs, Conn.) 45.1 (2017): 45–68. Web.

Sheila Murnaghan and Deborah H. Roberts, Childhood and the Classics Britain and America, 1850–1965, Oxford: OUP, 2018, 121–129.

Addenda

Illustration by Paul Bransom from 1913 edition. Public domain, retrieved from Archive.org (accessed: September 30, 2022).