Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Фаддей Францевич Зелинский, Античный мир. Эллада. Ч. 1. Сказочная древность: Вып. 1 – 3 [Antichnyj mir. Ellada. Part 1. Skazochnaya drevnost’]. Петроград: Издательство М. и С. Сабашниковых, 1922 – 1923.

Вып. 1. Кадм и Кадмиды – Персей – Аргонавты, Петроград: Издательство М. и С. Сабашниковых, 1922, 88, [2] pp.;

Вып. 2. Геракл – Лабдакиды – Афины, Петроград: Издательство М. и С. Сабашниковых, 1922, 113, [5] pp.

Вып. 3. Троянская война - Конец царства сказки, Петроград: Издательство М. и С. Сабашниковых, 1923, 100 pp.

Polish edition: Tadeusz Zieliński, Świat antyczny. Część pierwsza: Starożytność bajeczna. Warszawa – Kraków: Wydawnictwo J. Mortkowicza, 1930, 464, [5] pp.

Available Onllne

Russian edition available at Rusneb.ru. From RGB [Российская государственная библиотека (РГБ)] collection (accessed: September 26, 2022).

Polish edition available at Polona (accessed: October 28, 2021).

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Mythologies

Myths

Target Audience

Crossover (children, teenagers, young adults, adults)

Cover

Scans of the first edition retrieved from Rusneb.ru (accessed: September 26, 2022).

Cover available at Polona, public domain.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Paulina Kłóś, University of Warsaw, paulina.klos@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph of the Author, courtesy of Oleg Lukianchenko, the Author’s Grandson.

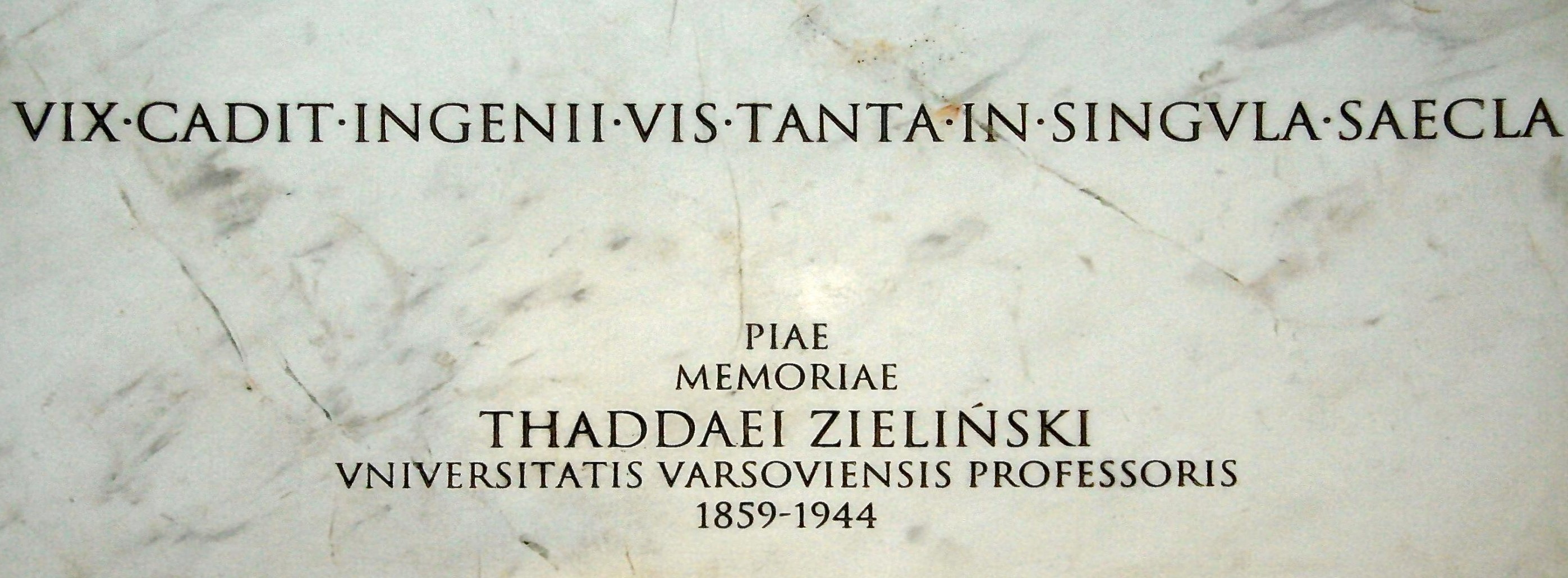

Tadeusz Zieliński

, 1859 - 1944

(Author)

Tadeusz Zieliński was one of the most important classical scholars of his time and a fervent promoter of classical culture and education. A philologist, ancient historian, historian of religion, essayist and translator (Zieliński translated several classical texts, including plays by Sophocles and Euripides, into Russian), equally at ease both in Greek and Roman literature; belonging to three cultures, he wrote in Russian, German, and Polish. Educated in St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Munich, and Vienna, he became a professor at the St. Petersburg University (1887–1920) and later at the University of Warsaw (1921–1935); he was revered by his students and by later generations of classicists as an inspiring teacher, ground-breaking researcher, and distinguished scholar who i.a. recognized the value of reception studies long before they became popular.

He was a member of the Polska Akademia Umiejętności [Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences]; Doctor honoris causa of multiple universities (including the University of Oxford, University of Athens and Jagiellonian University). His decorations include the Order of Polonia Restituta (for outstanding achievements in national culture) and the Greek Order of the Phoenix, 2nd Class. He was a colourful, unforgettable, and hugely popular figure in pre-war Poland; an exceptional, magnetic speaker, he was constantly invited to speak at home and abroad and greatly enjoyed his extensive travels, especially to the Mediterranean countries, as shown in his correspondence. At the initiative of Professor Jerzy Axer, the students of his students honoured him by a commemorative tablet at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw (below, phot. by Robert Przybysz).

Zieliński’s multilingual bibliography numbers over nine hundred works in the fields of classical philology, ancient history, ancient culture and religion, e.g. monographs on Cicero (Cicero im Wandel der Jahrhunderte, 1897), Sophocles (Sofokles i jego twórczość tragiczna [Sophocles and his Tragedies], 1928), and Horace (Horace et la société romaine du temps d’Auguste, 1938) or his six-volume work on ancient religions Religie świata antycznego [Religions of the Ancient World] (1918–1999). The last two volumes (the fifth volume’s manuscript was destroyed in a fire during the German bombardment of Warsaw in 1939) were written and completed by Zieliński during WW2. They remained unpublished for several decades due to the hostility of Communist authorities towards the great scholar. These volumes are a testament to his remarkable erudition and reflect a specific, spiritual and philosophical vision that developed in his later years. Furthermore, his autobiography (1924) was written in German and intended for his children. During WW2 and up until his last days (1939–1944), he jotted down his thoughts in his Polish diary, as well as his letters, especially those to his youngest daughter Ariadna in Russia (1922–1937) and the exchange of letters between his children in Germany, Russia and Japan (1958–1969) are of invaluable assistance in understanding Zieliński’s complex personality.

Among his works designed to popularise classical culture, there are also some examples of children’s literature.

Sources:

Zieliński, Thaddäus, Mein Lebenslauf – Erstausgabe deutschen Originals – und Tagebuch 1939–1944, Herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Jerzy Axer, Alexander Gavrilov und Michael von Albrecht; unter Mitwirkung von Hanna Geremek, Piotr Mitzner, Elżbieta Olechowska und Anatolij Ruban, Frankfurt am Mein: Peter Lang, 2012.

Olechowska, Elżbieta, ed., Tadeusz Zieliński (1859–1944). W 150 rocznicę urodzin, Warszawa: IBI AL UW, KNoKA PAN, 2011.

Bio prepared by Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Translation

Polish: Starożytność bajeczna, trans. Julia Wieleżyńska, Gabriela Pianko, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo J. Mortkowicza, 1930.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Starożytność bajeczna [The Fabulous Antiquity] is the first part of the Świat antyczny [The Ancient World] series – four books by Tadeusz Zieliński about the past of Ancient Greece and Rome. It is a compilation of the most important and most beautiful Greek myths. Zieliński chose an original way to present them to the readers – he adapted the versions of myths transmitted in the Athenian tragedies of 5th century BC. He concentrated on the presentation of heroes. In his view, these versions have the greatest potential to fascinate young readers. The depictions of events in the lives of, among others, Perseus, Hercules and even Oedipus are narrated in a lively language and have the power to affect the reader emotionally. The book presents the gorgeous history of Greek mythology and serves as an introduction and an invitation to the whole series.

Analysis

The scholarly work of Professor Zieliński as a classicist had been strongly constrained after the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, so he decided to fill his spare time with a new activity. He prepared an elaborate cycle to broadly popularise the ancient world, especially among young audiences. After his move to Warsaw, the first part of the tetralogy was published in 3 volumes in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in Russian. Still, Zieliński immediately started making efforts to release a Polish edition. He appreciated Mythology by Jan Parandowski as “beautifully written” (p. 466). N.B. Parandowski wrote the preface to the first Polish edition published after WW2 in 1957.

The myths discussed in the book have tragic characters, as their sources are mainly ancient dramatic works. However, the book is well adapted for young readers and children; the author uses “fabulous” language, appropriate structure and narrative devices. First off, individual chapters and sub-chapters are written like bedtime stories. The text is divided into smaller parts, easy-to-read or to listen to, to not discourage children by the big volume. In this way, even less relevant subplots and characters are mentioned when discussing other plots and presented in detail. A good example is provided by the story of Alcmaeon, who killed his mother, rarely presented in other mythologies for children containing only the main myths.

The stories omitted at the beginning appear elsewhere, a great instance of a frame narrative – telling stories within a story. For example, the myth of the world’s origin is told to the young apprentice, Jason, by Cheiron. The boy, Jason, asks questions about the world and the gods and Cheiron, after the story of the world’s origin, tells him about the golden era, Prometheus, the deluge, the gods, human destiny and old age. All these tales are enriched with a moral lesson: respect your parents, respect guests, and respect foreigners. Another story within a story is told while presenting the myth of Ino and Athamas. As Ino roasts seeds to prevent them from sprouting, which gives her an excuse to blame her stepchildren for the drought, she is told to commit sacrilege against Demeter, which Athamas’ people comment on. One of them directly asks a priest, “how did this happen?” (p. 35), and this way makes the priest tell the myth of Demeter and Kore and explain the origin of agriculture and the Eleusinian Mysteries. This story is cleverly interwoven into the chapter about Cadmus. The myth of Phaethon is told by Heliades – the poplar trees – when Heracles stops by the river Eridanus (p. 182). Similarly, Heracles’ katabasis to the Underworld to capture Cerberus becomes the reason to tell the myth of Orpheus (p. 188), another man who dared to enter Hades’ realm alive, and a pretext to describe the Underworld in detail.

The author introduces additional stories in the manner used by Ovid and shows that the myths are inter-connected and relevant to each other, and tells the young readers what the ancient Greeks thought or believed. Sometimes, Zieliński also uses direct comments; for instance, when he describes the plague in Thebes or explains why Acrisius could not just kill Perseus, his own blood, he says, “ancient Greeks believed that plague was a punishment sent by Apollo (…) usually for any religious offence” (p. 227).

To adapt the stories to a child’s sensitivity, Zieliński repeatedly spares the young readers by omitting drastic details, even though he uses tragedies as his sources. For instance, he glosses over baby Oedipus’ mutilation or the execution of Odysseus’ serving maidens. Certain terrible situations are omitted in the main story but retold by other characters as rumours. This narrative strategy is used when he tells the myth of Heracles. In Zieliński’s interpretation, when in Hades during the 11th labour, Heracles meets the shade of Deianeira (if she is already dead, she could not cause his death). Having completed the last labour in the Hesperides’ garden, the hero is given the apples as a reward, and Athena and Hermes lead him to Olympus. His madness and death (by fire) are not mentioned until Eurystheus summons Thyestes and Atreus. They bring him the rumours about Megara, the madness, Iphitus’ accidental killing, Heracles’ revenge on Eurytus, the capturing of Iole and Deianeira’s fatal jealousy. As these events are presented as rumours, Heracles’ character remains intact, but the reader does not remain unaware of the other versions of the myth. Even when the tragic fates of the characters are discussed, Zieliński does not emphasise them and does not simply leave the reader without comment. When Macaria, Heracles’ daughter, sacrifices herself to save Athens from Eurystheus’ army, she is told to say farewell to everyone and join Deianeira and Amphitryon on the way to eternal happiness (p. 219), which may comfort the young reader. Similarly, when describing Thyestes’ feast, Zieliński says that even the sun cast his eyes down, causing a darkness that would hide this horror (p. 220).

The style Zieliński uses is full of dialogues, elegant descriptions and resembles the template familiar to children from 19th-century fairy tales. To maintain the convention of a fairy tale in his fabulous mythology, he does not start from the beginning, i. e., from the Earth emerging from the Chaos, as many textbooks about Greek mythology do. Zieliński uses the opening formula of a fairy-tale: “Once upon a time in a distant land of Phoenicia, there lived a mighty king named Agenor. He had three sons and a beautiful daughter, Europe. It happened once, that the royal princess…” (p. 3). Thus he invites the child readers to immediately immerse themselves in medias res, in the story of Cadmus and the Cadmids. In accordance with the title, the fairy tale convention is maintained throughout the entire book. For example, in Perseus’ myth, the Gorgons live in a mysterious castle on a hillside at the world's edge. The castle is gloomy, surrounded by saw-edged walls and guarded by Graeae, described as the ugliest creatures in the world. The convention of a fairy-tale also applies to the punishment of Polydectes, who is punished justly and proportionally to his wickedness. The kingdom is given to Dictys, a reward for his uprightness. Zieliński also re-uses the popular motif of three wishes, known from Pushkin’s tale of the fisherman and the fish or Afanasyev’s skazka. In the water realm, Poseidon gives Theseus three wishes (p. 283) while Amphitrite crowns him with a golden wreath which later provides him with light in the Labyrinth. Similarly, the necklace of Harmonia, made of cursed dragon’s gold, becomes a leitmotif present throughout the narration. Described in many ancient sources as an unlucky jewel bringing misfortune to its female bearers, it bears the responsibility for the tragic fate of its seven owners. Its seven diamonds, one after another, turn scarlet when they doom Harmonia’s heiresses: Semele, Agave, Dirce, Niobe, Iocasta, Eriphyle and Alphesiboea. It is a device that ties together (p. 263) five of the seven chapters.

Further Reading

Iwaszkiewicz, Jarosław, “Do Tadeusza Zielińskiego”, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 425–426.

Krawczuk, Aleksander, “Tadeusz Zieliński — życie i dzieło. Tadeusza Zielińskiego Świat antyczny [a foreword]”, in Tadeusz Zieliński, Starożytność bajeczna, Katowice: Śląsk, 1987, 7–24.

Kumaniecki, Kazimierz, “Tadeusz Zieliński”, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 387–393.

Łuria, S. J., “Wspomnienia o prof. Tadeuszu Zielińskim i jego metodzie motywów rudymentarnych”, trans. Oktawiusz Jurewicz, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 406–418.

Marciniak, Katarzyna, “ (De)constructing Arcadia: The Polish Struggles with History and Differing Colours of Childhood in the Mirror of Classical Mythology”, in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Bril: Leiden–Boston, 56–82.

Mortkowicz-Olczakowa, Hanna, “Wspomnienie o Tadeuszu Zielińskim [z listami T. Zielińskiego i W. Zielińskiej z 1942/43 r.]”, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 428–433.

Novotný, František, “Tadeusz Zieliński,” Listy Filologické / Folia Philologica 83.1 (1960): 1–27.

Pianko, Gabriela, “Bibliografia prac Tadeusza Zielińskiego”, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 437–461.

Srebrny, Stefan, “Ze wspomnień ucznia”, Meander: miesięcznik poświęcony kulturze świata starożytnego 8–9 (1959): 394–405.

Vasmer, Max, “Zur Hundertsten Wiederkehr Des Geburtstages Von Tadeusz Zielinski”, Osteuropa 9.12 (1959): 835–836.

Zaborowski, Robert, “Tadeusz Zieliński (1859–1944) i Wincenty Lutosławski (1863–1954). Próba porównania biografii (w sześćdziesiątą i pięćdziesiątą rocznicę ich śmierci)”, Prace Komisji Historii Nauki Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności 8 (2007): 33–81 (accessed: October 27, 2021).

Zieliński, Tadeusz, Autobiografia, Dziennik 1939–1944, Hanna Geremek and Piotr Mitzner, eds., Warszawa: Wydawnictwo DiG, 2005.

Zieliński, Tadeusz, Our Debt to Antiquity, trans. Herbert Augustus Strong and Hugh Stewart, London: Routledge & Sons, 1909 (accessed: October 27, 2021).

Addenda

The entry is based on the Polish edition:

Tadeusz Zieliński, Starożytność bajeczna, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo J. Mortkowicza, 1930.

The pagination quoted in the analysis refers to this edition.