Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

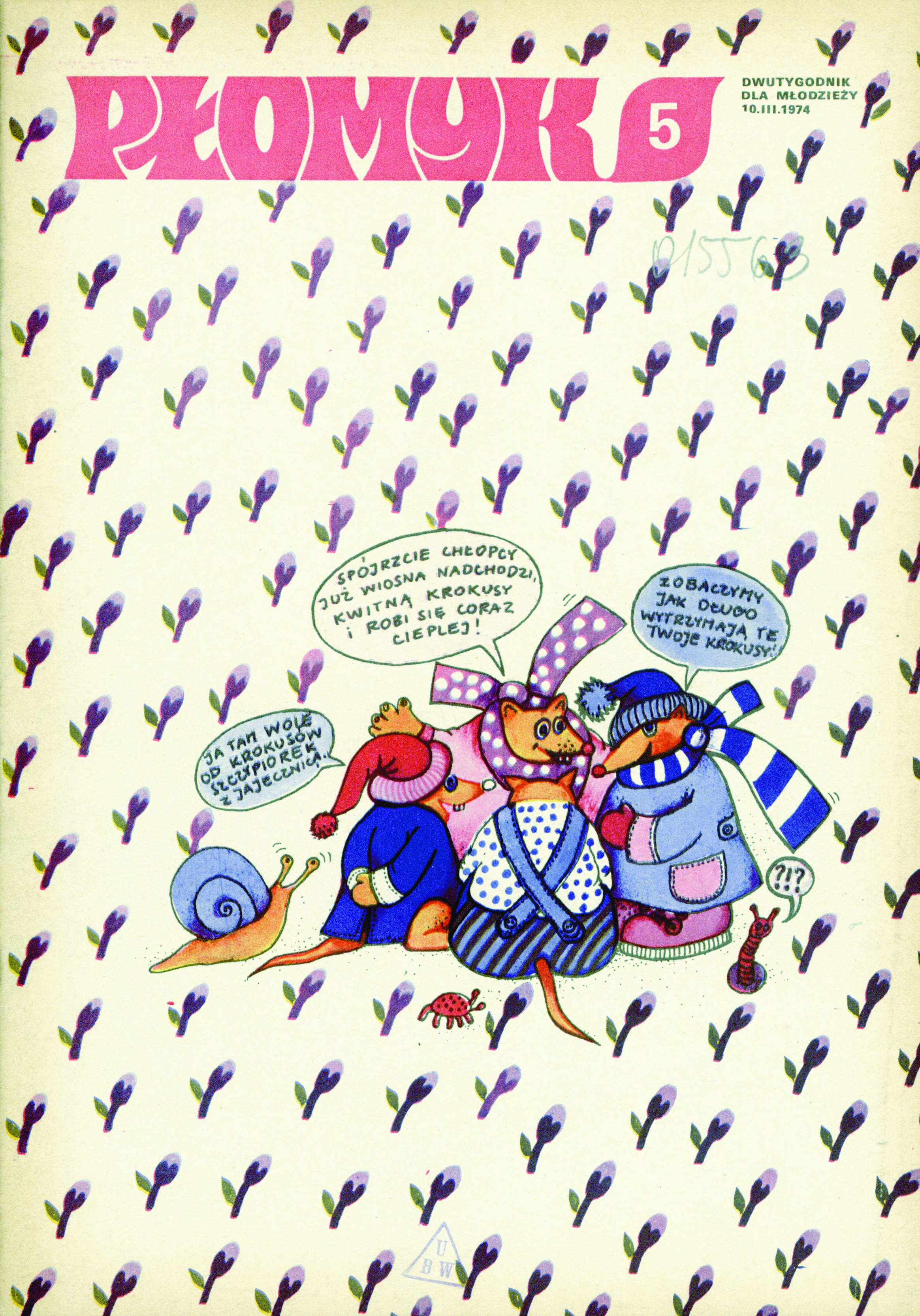

Tadeusz Zieliński, “Opowieść o ojcu Ikara – mądrym Dedalosie”, Płomyk 5 (1974): 146–147.

ISBN

Genre

Adaptation of classical texts*

Adaptations

Myths

Target Audience

Children (and adolescents)

Cover

Courtesy of Nasza Księgarnia, the Publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Tomasz Królak, University of Warsaw, ufnal8@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph of the Author, courtesy of Oleg Lukianchenko, the Author’s Grandson.

Tadeusz Zieliński

, 1859 - 1944

(Author)

Tadeusz Zieliński was one of the most important classical scholars of his time and a fervent promoter of classical culture and education. A philologist, ancient historian, historian of religion, essayist and translator (Zieliński translated several classical texts, including plays by Sophocles and Euripides, into Russian), equally at ease both in Greek and Roman literature; belonging to three cultures, he wrote in Russian, German, and Polish. Educated in St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Munich, and Vienna, he became a professor at the St. Petersburg University (1887–1920) and later at the University of Warsaw (1921–1935); he was revered by his students and by later generations of classicists as an inspiring teacher, ground-breaking researcher, and distinguished scholar who i.a. recognized the value of reception studies long before they became popular.

He was a member of the Polska Akademia Umiejętności [Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences]; Doctor honoris causa of multiple universities (including the University of Oxford, University of Athens and Jagiellonian University). His decorations include the Order of Polonia Restituta (for outstanding achievements in national culture) and the Greek Order of the Phoenix, 2nd Class. He was a colourful, unforgettable, and hugely popular figure in pre-war Poland; an exceptional, magnetic speaker, he was constantly invited to speak at home and abroad and greatly enjoyed his extensive travels, especially to the Mediterranean countries, as shown in his correspondence. At the initiative of Professor Jerzy Axer, the students of his students honoured him by a commemorative tablet at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales” of the University of Warsaw (below, phot. by Robert Przybysz).

Zieliński’s multilingual bibliography numbers over nine hundred works in the fields of classical philology, ancient history, ancient culture and religion, e.g. monographs on Cicero (Cicero im Wandel der Jahrhunderte, 1897), Sophocles (Sofokles i jego twórczość tragiczna [Sophocles and his Tragedies], 1928), and Horace (Horace et la société romaine du temps d’Auguste, 1938) or his six-volume work on ancient religions Religie świata antycznego [Religions of the Ancient World] (1918–1999). The last two volumes (the fifth volume’s manuscript was destroyed in a fire during the German bombardment of Warsaw in 1939) were written and completed by Zieliński during WW2. They remained unpublished for several decades due to the hostility of Communist authorities towards the great scholar. These volumes are a testament to his remarkable erudition and reflect a specific, spiritual and philosophical vision that developed in his later years. Furthermore, his autobiography (1924) was written in German and intended for his children. During WW2 and up until his last days (1939–1944), he jotted down his thoughts in his Polish diary, as well as his letters, especially those to his youngest daughter Ariadna in Russia (1922–1937) and the exchange of letters between his children in Germany, Russia and Japan (1958–1969) are of invaluable assistance in understanding Zieliński’s complex personality.

Among his works designed to popularise classical culture, there are also some examples of children’s literature.

Sources:

Zieliński, Thaddäus, Mein Lebenslauf – Erstausgabe deutschen Originals – und Tagebuch 1939–1944, Herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Jerzy Axer, Alexander Gavrilov und Michael von Albrecht; unter Mitwirkung von Hanna Geremek, Piotr Mitzner, Elżbieta Olechowska und Anatolij Ruban, Frankfurt am Mein: Peter Lang, 2012.

Olechowska, Elżbieta, ed., Tadeusz Zieliński (1859–1944). W 150 rocznicę urodzin, Warszawa: IBI AL UW, KNoKA PAN, 2011.

Bio prepared by Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The story is a brief retelling of Daedalus’ myth. It begins with a version of the story of the Minotaur, without a mention of Pasiphaë mating with the bull but with the birth of a monstrous offspring attributed to Minos’ hubris. The King’s excessive pride seeks to hide this shame. Daedalus, a famous architect and inventor, who happens to need a commission and shelter, may help. King Minos commissions Daedalus to build the Labyrinth. Then follows a description of Daedalus’s great engineering talent and a mention the death of his nephew, Talos, which forced him to leave Athens. Then comes the story of Daedalus’ and Icarus’ flight from Crete on the wings that Daedalus constructed and of the death of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun. We also learn how Daedalus hid in the Sicilian town of Camicus, under the protection of King Cocalus, and how Minos found him by announcing a great prize for anyone who could pull a thread through a snail’s shell without damaging it; Daedalus rose to the challenge by putting inside an ant attached to a thread; in order to escape from the shell, the insect found its way through and at the same time marked the passage with the thread. The story ends with King Minos’ attempt to take back Daedalus. He was thwarted by Cocalus’ daughters, who saved the inventor by substituting boiling water for the cold water prepared for Minos to rinse himself after his bath. Minos died instantly.

Analysis

This adaptation of Daedalus’ myth was published 30 years after Zieliński’s death as a separate short story prepared for young readers of the bi-weekly Płomyk [The Flame]. It was adapted with minor changes from a chapter (“Mądrość Dedala” [Daedalus’ Wisdom], accessed: March 7, 2022) of Zielinski’s Polish edition of Сказочная древность [The Fabulous Antiquity]. The extensive chapter was abbreviated to create a coherent short story, and the spelling was updated according to the rules current in 1974. It covers Daedalus’ life story, from his young years spent in Athens to the stay at the Sicilian court of King Cocalus.

The story is well adapted to children’s perception skills: the narrative is divided into chapters, subchapters and even smaller sections following the convention of bedtime stories. The language is elegant and straightforward; difficult issues are not left without explanation, comment or, if required, a word of comfort. Although some themes were removed as inappropriate, like for instance, Pasiphaë’s lust for the bull, other plots, rarely appearing in children’s adaptations of Daedalus’ myth because of cruelty or violence, were not eliminated. They provide the young reader with an indication of the complexity of human nature, with the possible impact of circumstances on human behaviour and further consequences of various decisions.

The first difficult issue presented is Minos’ excessive pride. He is not explicitly accused of being guilty of hubris, but as he considers himself almost equal to gods, he is obviously asking for punishment. The Minotaur is born to Minos as a warning from the gods not to cross the line between high self-esteem and impiety. Wicked deeds are punished and bring shame to the perpetrator. The second issue often considered inappropriate for children is the reason for Daedalus’ exile – his involvement in his nephew’s death. Many authors remove this narrative from their adaptations to avoid shocking child readers. Zieliński, however, prefers to be honest with the reader – in this version, Daedalus causes the boy’s death, but the reader is left with an impression that it was manslaughter, not cold-blooded murder. While he is still guilty of an unintended death, an excuse is suggested: the nephew became haughty and lacked respect for his master. It was easy for Daedalus to lose his temper during an argument. Of course, Zieliński does not absolve the protagonist and emphasizes his feeling of remorse; because of the blood he spilt, Daedalus was haunted by nightmares. It is impossible not to conclude that – according to the fairy-tale logic of life for a life – the nephew’s death is paid for with Icarus’. Similarly, Minos also gets his just deserts. The first warning – the birth of the monstrous son – misses the mark, as he does not improve, remains imperious, ruthless. He relentlessly pursues Daedalus, and with his overwhelming might, terrorizes the poor King Cocalus. But fate catches up with Minos: he expires in a boiling bath, leaving Daedalus to live the rest of his natural life in peace, as he already dearly paid his dues.

An original aspect of Zieliński’s tale is that he demonstrates to the reader that life does not end with the death of a dear one. Many other authors who adapted Daedalus’ myth for children conclude the story at the exact moment of Icarus’ fall, as if there were no words to describe what happened next, or as if Daedalus’ life was over at the same time. It is undeniable that Daedalus lost his son, but Zieliński gives him another important duty that he has to complete despite or because of his grief: to build a cenotaph for Icarus. An edifice for his late son’s soul was intended as redemption for building the Labyrinth for an evil ruler. Daedalus then prays to Athena and sacrifices the fatal wings to her as a “pious debt”. Once paid, he can seek a quiet haven to spend the rest of his life.

Further Reading

Olechowska, Elżbieta, ed., Tadeusz Zieliński (1859–1944). W 150 rocznicę urodzin, Warszawa: IBI AL UW, 2011.

Marciniak, Katarzyna, “(De)constructing Arcadia: The Polish Struggles with History and Differing Colours of Childhood in the Mirror of Classical Mythology”, in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2015, 56–82.

Zieliński, Tadeusz, Autobiografia. Dziennik 1939–1944, do druku podali Hanna Geremek i Piotr Mitzner, Warszawa: OBTA & Wydawnictwo DiG, 2005.

"Zieliński, Tadeusz", in Zdzisław Piszczek, ed., Mała encyklopedia kultury antycznej, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1990, 803.

Zielinski, Thaddäus, Mein Lebenslauf — Erstausgabe des deutschen Originals — und Tagebuch 1939–1944, Hrsg. und eingeleitet von Jerzy Axer, Alexander Gavrilov und Michael von Albrecht. Unter Mitwirkung von Hanna Geremek, Piotr Mitzner, Elżbieta Olechowska und Anatolij Ruban, Studien zur klassischen Philologie, 167, Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2012.