Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

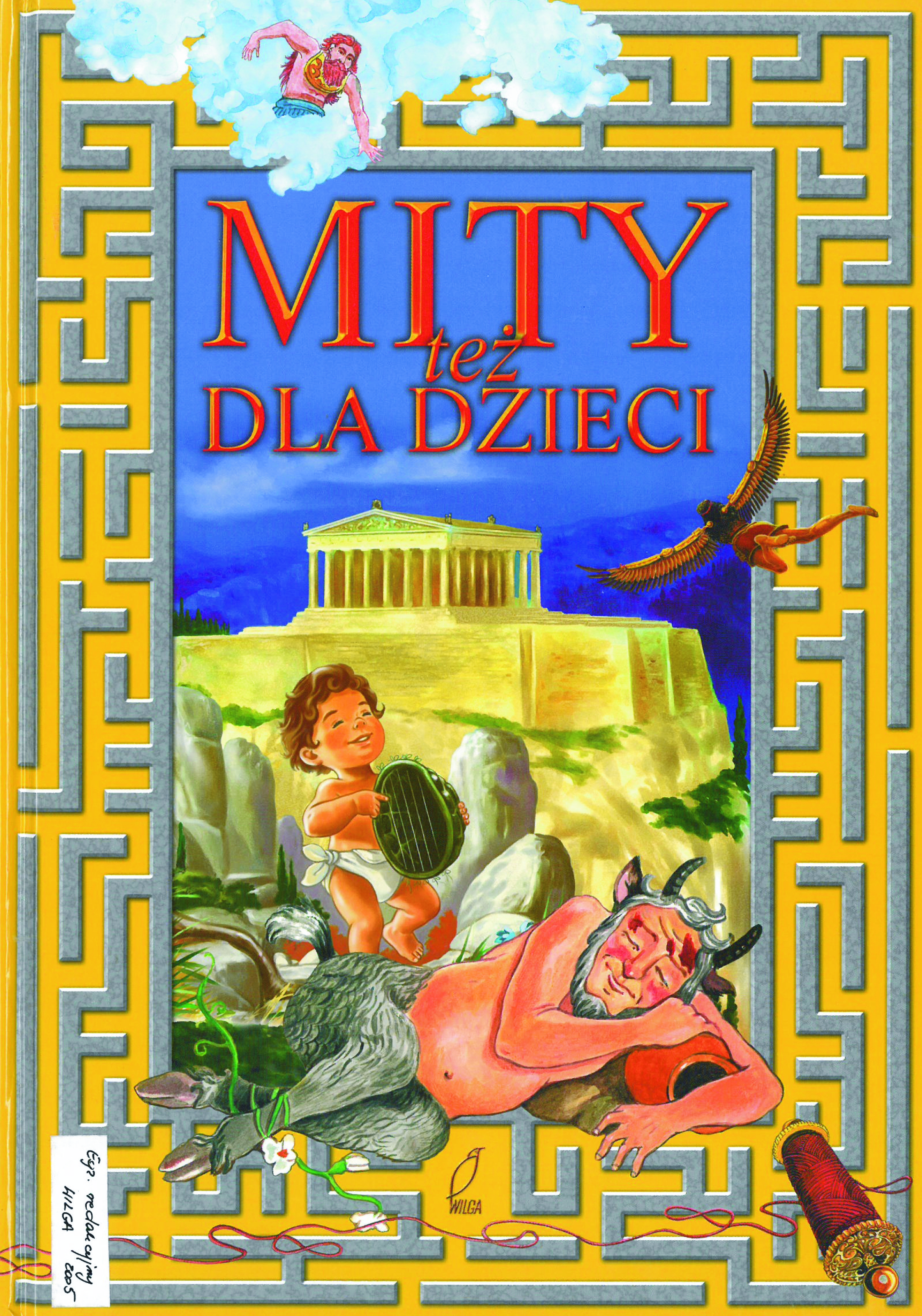

Grzegorz Kasdepke, Mity też dla dzieci. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Wilga, 2005, 20 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Scan of the cover kindly provided by Wydawnictwo Wilga.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Maria Karpińska, mariakarpinska@student.uw.edu.pl.

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph by Katarzyna Marcinkiewicz, courtesy of the Author.

Grzegorz Kasdepke

, b. 1972

(Author)

Born in Białystok, now lives in Warsaw. Attended Faculty of Journalism and Political Science at the University of Warsaw. He made his journalistic debut in the weekly “Polityka.” Author of books for children and teenagers, among them many bestsellers. From 1995 to 2000: Editor-in-Chief of the popular magazine for children “Świerszczyk” [The Little Cricket]. Wrote a number of radio-plays for children, as well as scripts for TV programs and series (Ciuchcia [The Choo-Choo Train], Budzik [The Alarm Clock], Podwieczorek u Mini i Maxa [Afternoon Tea at Mini and Max]). Awarded a number of literary prizes. In his books, Kasdepke attempts to explain to his young readers the complicated adult world demonstrating a sense of humour and an understanding of their needs, like for example in books and audiobooks: Co to znaczy... 101 zabawnych historyjek, które pozwolą zrozumieć znaczenie niektórych powiedzeń [What Does It Mean... 101 Funny Stories Helping to Understand the Meaning of Some Expressions], 2002; Bon czy ton. Savoir–vivre dla dzieci [Bon or Ton. Savoir–vivre for Children], 2004; Horror! Skąd się biorą dzieci [Horror! Where Do the Children Come from?], 2009; Kocha, lubi, szanuje, czyli jeszcze o uczuciach [Loves, Likes, Respects, or Again about Feelings], 2012; W moim brzuchu mieszka jakieś zwierzątko [A Little Animal Lives in My Tummy], 2012. He is also the author of crime stories for children – a series of books about Detektyw Pozytywka [Musical Box Detective], 2005–2011. Received the Kornel Makuszyński Prize for his book Kacperiada. Opowiadania dla łobuzów i nie tylko [Kacperiada. Stories for Rogues and not Only], 2001, inspired by his son Kacper. He considers himself “a 100 per cent fairytale writer.” In a recent TV interview the author confirmed the preparation of a new book for children inspired by ancient mythology – Banda trupków i sandały Hermesa [A Gang of Corpsies and Hermes’ Sandals]. Kasdepke wrote about twenty short stories – adaptations of myths, published in five volumes with varying contents, see descriptions below (with a particular stress on the presentation of the most recent volumes). In 2019 he was awarded the Order of the Smile, an international award given by children since 1968.

Bio prepared by Dorota Rejter, University of Warsaw, dorota@bazylczyk.com, and Maria Karpińska, University of Warsaw, mariakarpinska@student.uw.edu.pl

Witold Vargas

, b. 1986

(Illustrator)

Witold Vargas is a writer, storyteller, illustrator, graphic designer and musician born in Bolivia. His parents, Ernesto Vargas and Anna Przerwa-Tetmajer were architects. His most famous and recognizable drawings illustrate bestiaries presenting mythical creatures, especially from Slavic mythologies and folklore. Currently, he is working with Paweł Zych on the series Legendarz [The Legendary], which already includes Bestiariusz słowiański [Slavic Bestiary] in two volumes, which has inspired many creators of the Slavic fantasy genre – writers, storytellers or computer game designers, including the creators of Wiedźmin – Dziki gon [The Witcher – Wild Hunt] RPG.

Sources:

Taniaksiazka (accessed: June 9, 2022).

Sztuka.agraart (accessed: June 9, 2022).

Polawiaczeperel (accessed: June 9, 2022).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Translation

See the entry Mity dla dzieci – Zeus & spółka.

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

The text was incorporated to the ten myths collection: Grzegorz Kasdepke, ill. Ewa Poklewska-Koziełło, Mity dla dzieci – Zeus & spółka, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Literatura, 2011, 96 pp.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The collection retells three myths adapted for children. The first one presents the beginnings of the world and the rule of the old Greek gods over the Earth until the Olympian gods replaced them. The second myth is the story of Theseus and his heroic deeds on Peloponnesus and Crete, and the last myth is focused on the abduction of Europa, Cadmus’ search and the foundation of Thebes.

Analysis

The author writes lightly, and his style is full of vivid comparisons, descriptions, and humorous dialogues. The language is elegant yet clear as the vocabulary is simple and includes many familiar phrases. This kind of storytelling brings the ancient characters closer to contemporary children.

The author begins ab ovo, i.e., from the origins of the world, showing them as chaotic and full of imperfections, typical of activities one might do for the first time. The old gods are presented as nervous characters living under pressure and distress. Ordering the new world makes them overreact and argue due to the constant burden of duties. That is why Ouranos is replaced by his son Cronus who introduces the golden age of wise rule, but then himself becomes corrupted by power and the fear of losing it. The myth includes humorous elements (the Hecatoncheires babies move mountains and splash water out of the oceans, Cronus fails to reach the bathroom and is forced to vomit in public), allowing the child reader to look at mythological characters as less distant from ordinary people, whether adults or children.

The next myth focuses on young Theseus following his dream of being a hero. However, his role model is not James Bond or Superman but Hercules. On his way to Athens, he behaves just like his hero, cleansing the land from evildoers and embarking on the ship to Crete with the same firm goal: to save the land from the monster devouring human flesh. Despite the mockery at Minos’ court and the real threat lurking in the corridors of the Labyrinth feared by the Athenian youths, Theseus follows his dream. In the moment of intense fear, he summons his courage, thinking of Hercules and finally vanquishes the monster, which appears easier than overcoming his fear. Eventually, Theseus becomes a hero and a role model for others, showing the reader that it makes sense to follow one’s dreams, even if they seem impossible to fulfill.

The last myth begins with a description of the siblings Europa and Cadmus. The girl is introduced to serve as a caution not to approach unknown animals, even if they look tame, friendly, and gentle, as the strange animals could potentially bite, kick or scratch a child. The disappearance of Europa shows her father is so fond of his daughter that he seems not to care about his three sons. He orders them to look for Europa, whatever the cost. Then the story focuses on the character of Cadmus, a brave man who is left alone and has to face horrible challenges. Unable to return home, he loses his team, defeats the dragon to avenge his comrades, and starts a new life by founding the city of Thebes. The Theban myth, chosen by the author to be the third story, not only provides readers with a warning against unknown animals and explains the Greek roots of the name of the European continent but also offers children an important part of the mythical heritage in the memorable figure of Cadmus and the spartoi people, grown from a dragon’s teeth.

Further Reading

Hajduk-Gawron, Wioletta, "Sfera linguakultury jako niezbędny element integracji”, Postscriptum Polonistyczne 2 (2019): 247–258 (accessed: May 7, 2021).

Niesporek-Szamburska, Bernadeta, “Dobre maniery, czyli o dydaktyzmie we współczesnej literaturze dziecięcej” in Bernadeta Niesporek-Szamburska and Małgorzata Wójcik-Dudek, eds. Nowe opisanie świata: literatura i sztuka dla dzieci i młodzieży w kręgach oddziaływań, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2013, 55–69 (accessed: May 7, 2021).

Plieth-Kalinowska, Izabela, "Świadomość językowa uczniów klas trzecich szkoły podstawowej”, Przegląd Pedagogiczny 1 (2015): 111–118 (accessed: May 7, 2021).