Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

In installments: Joe Alex, Czarne okręty, vol. 1–11, ill. Bohdan Wróblewski. Warszawa: Biuro Wydawnicze "Ruch", 1972–1975.

Part 1: Ofiarujmy bogom krew jego, 1972, 86 pp.

Part 2: Oto zapada noc mroczna, 1972, 103 pp.

Part 3: Abyś nie błądził w obcej ciemności, 1972, 99 pp.

Part 4: A drogi tej nie zna nikt, 1974, 90 pp.

Part 5: Cień nienawiści królewskiej, 1974, 95 pp.

Part 6: Lew was rozszarpał płowy, 1974, 75 pp.

Part 7: Ciemny pierścień zakrzepłej krwi, 1974, 54 pp.

Part 8: Kraina umarłych liści, 1975, 103 pp.

Part 9: Posejdon o białym obliczu, 1975, 84 pp.

Part 10: Niechaj umrze o wschodzie słońca, 1975, 101 pp.

Part 11: Sam bądź księciem, 1975, 123 pp.

In four-volume edition: Joe Alex, Czarne okręty, vol. 1–4. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1978.

Part 1: Ofiarujemy bogom krew jego, 228 pp.

Part 2: Cień nienawiści królewskiej, 220 pp.

Part 3: Kraina umarłych liści, 249 pp.

Part 4: Sam bądź księciem, 244 pp.

Genre

Action and adventure fiction

Historical fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover

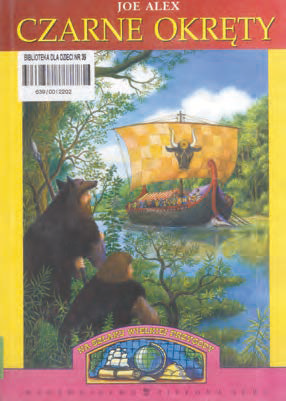

Cover

Cover of the 2001 edition. Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Joanna Kozioł, University of Warsaw, joasia7777@interia.pl

Analysis: Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

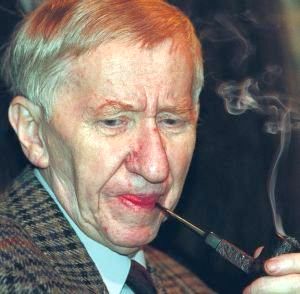

Photograph courtesy of Rotary Club Cracow.

Maciej Słomczyński

[Joe Alex] , 1922 - 1998

(Author)

Maciej Słomczyński* was a writer, screenwriter, and translator. Son of an English woman Marjorie Crosby and of Merian C. Cooper, an American aviator, officer of the American Air Force and Polish Air Force (The Kościuszko Squadron), and later a film director (he directed and produced King Kong in 1933). When Cooper left Poland, Marjorie remained and married Aleksander Słomczyński. Maciej was adopted by his stepfather. As a child he lived in Milanówek (near Warsaw) but grew up surrounded by English culture; as he said himself, his first language was English.

He attended the Piarist Gymnasium in Rakowice (today a Cracow suburb). In 1939 he passed his final high school exam in Wejherowo (a town in Pomerania near Gdańsk). In the same year, he returned to Milanówek and became involved in the Resistance: in 1941, he joined Konfederacja Narodu (Confederation of the Nation, a Polish resistance organization), and in 1943, he became a soldier of Armia Krajowa [Home Army]. In 1944 he was arrested by the Germans and imprisoned in Pawiak, the notorious Gestapo prison in Warsaw; fortunately he escaped but was later captured again and deported to a labour camp in Austria; he managed to get away from there by escaping to Switzerland. After that, he worked for the 3rd US Army under gen. Patton and the American gendarmerie in Paris. He returned permanently to Poland in 1947, lived in Łódź and later in Cracow. A very prolific writer, he published his first text, Ballada o kucharzu i literacie [Ballad about the Cook and the Writer], in a Łódź weekly “Tydzień.” In 1947, he published a collection of poems for children, Makówka z Milanówka [Poppy Head from Milanówek]. During the Communist regime, he was suspected of being an English spy, and was invigilated.

He used a pen-name Joe Alex to sign his crime stories (Zmącony spokój Pani Labiryntu [Disturbed Peace of the Lady of the Labyrinth], 1965; Piekło jest we mnie [Hell Is in Me], 1975); screenplays (Zbrodniarz i panna [The Criminal and the Maiden], 1963; Gdzie jest trzeci król [Where Is the Third King], 1966), and an adventure novel in eleven volumes Czarne okręty [The Black Ships], 1972–1975. He also used the pen-name Kazimierz Kwaśniewski for some of his screenplays.

Słomczyński was also a prominent translator of many English language classics into Polish, i.e., Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, James Joyce’s Ulisses, and all of Sheakespeare’s plays. He wrote for Polish Radio Łódź, and Polish TV Teatr Sensacji “Kobra” [Theatre of Sensation “Cobra”]. Member of Stowarzyszenie Pisarzy Polskich [Polish Writers’ Association], and Rotary Club; Vice-Chairman of James Joyce’s International Foundation and, since 1973, member of the Irish Institute.

In 1997 he was awarded the Comander’s Cross with Star of the Order of Polonia Restituta (for outstanding achievements in national culture).

* The exact year of his birth, either 1920 or 1922, is the subject of argument even among members of his closest family. The date 1922 is postulated by Maciej Słomczyński’s daughter.

Sources:

Kucharczyk-Kubacka, Monika, Maciej Słomczyński. Bibliografia, Kraków: Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna w Krakowie, 2008.

"Maciej Słomczyński" in Jadwiga Czachowska; Alicja Szałagan, edd., Współcześni polscy pisarze i badacze literatury. Słownik biobibliograficzny, vol. 7: R–Sta, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 2001, 335.

Słomczyńska-Pierzchalska, Małgorzata, Nie mogłem być inny. Zagadka Macieja Słomczyńskiego, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2003.

Sucharski, Robert A., “Joe Alex (Maciej Słomczyński) and His Czarne okręty [Black Ships]: A History of a Trojan Boy in Times of the Minoan Thalassocracy,” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Hope: The Ancient Myths as Medicine for the Hardships of Life in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture, Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2021, 211–213.

Bio prepared by Joanna Kozioł, University of Warsaw, joasia7777@interia.pl

Translation

Czech: Černé koráby, vol. 1–2, trans. Anetta Balajková, ill. Zdeněk Mézl, Praha: Albatros, 1979.

Slovak: Čierne koráby, trans. Miroslav Janek, Bratislava: Mladé Letá, 1984–1986.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue (accessed: June 11, 2021), Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The action takes place around 2000 BC. The main character is a Trojan teenager (he is fourteen when the story begins), called Białowłosy (Towhead, literally “White-haired”) because of the colour of his hair. One day, he goes fishing. A great storm wrecks his boat but the crew of an Egyptian ship rescues him; their captain Ahikar takes him to Egypt and eventually sells him to a Phoenician priest (Het-Ka-Sebek) who serves the crocodile god Sebek; Towhead is going to be sacrificed to this god. Fortunately, he manages to kill the crocodile, and with the help of a Phoenician slave Lauratas, he escapes. For some time, Towhead and Lauratas hide in the tomb of a writer Nerau-tu. Before they can reach freedom, Lauratas is killed by a falling rock. Towhead, alone, is being chased by the Phoenicians. He is captured by warriors who are going to return him to the Phoenicians; in the nick of time, he is rescued by Terteus, son of the king of the isle of Sytnos. The two become friends and begin to journey together. On the way, they happen to rescue the younger son and grandson of Minos, king of Crete and eventually sail to that island. When they arrive in Crete, they find that Minos has died and his older son has replaced him as king. Afraid of dynastic complications, he sends his brother and nephew in search of the mysterious Land of Amber (the land on the southern shores of the Baltic Sea from where amber was transported to Rome; it was identified with Poland), hoping they never come back. The first stop on that journey is Athens, where they meet prince Theseus. They go on to Troy, home of Towhead, who is reunited with his parents. Then, they continue their journey (still with Towhead) to the unknown lands in the North. They have many more dangerous adventures. In the end, they reach the Land of Amber. When they return to Crete, people are pleased to see Minos’ younger son and grandson because during their absence, the older brother died and the island was devastated by Greeks and Trojans. Minos’ younger son jumps to his death from the roof of the palace; Minos’ grandson is named king but refuses to rule over a ruined kingdom and leaves with Terteus for his island of Sytnos. Towhead goes back to his parents in Troy.

Analysis

The novel’s plot is built as an adventure story and resembles the myth of the Argonauts, with plenty of traveling, adventures, and adversities for Towhead and his friends to overcome. At the same time, the text is similar to a historical novel placed in an undefined time frame. According to Robert Sucharski, this would be the Bronze Age, the second half of the second millennium BC as the novel refers to historical events and circumstances relevant to the period from the 19th to 13th century BC. However, it is impossible to date it more precisely, as facts from different centuries are mixed*.

Describing the protagonist’s adventures in various lands (such as Egypt, Crete, Greece, and so on), the author presents the life and culture of these countries, including elements stereotypical and recognizable to the reader, e.g., ancient Egyptian mummification or the Knossos labyrinth. Basing his story on commonly known facts, Słomczyński adds historical and fictional details of life in the ancient Mediterranean, making it a lively and interesting reading. Unsurprisingly, the adventures of Towhead start in Egypt, which seems to be well established in popular culture, especially in the 1970s, when the novel was published.

Robert Sucharski highlights that the characters’ names are rooted in names known from historical sources, which also applies to Slavic names.** An interesting trick was foregoing the name of the protagonist. He is called “Towhead” as he waits for a proper name during his initiation. I believe such a measure brings this character closer and allows the reader to identify with him.

As the story describes the coming-of-age process of the protagonist, Sucharski suggests looking for autobiographical references, comparing the mythical journey to the experience of Słomczyński’s escape from a concentration camp during World War II and to similar experiences his parents had:

“It is hard to count how many times Słomczyński saves his own life during World War Two: the odyssey of the prisoner of the Pawiak – the biggest Nazi political prison in occupied Poland; being moved to Gęsiówka – the Waffen-SS concentration camp in Warsaw; the escape from the camp and struggling through to Switzerland; crossing the Rhine in January; the internment camp in Aarau; the escape to liberated France; the service in the American Army in France; and finally the return to Poland. It is difficult to count the number of such cases in the life of his presumed biological father as well. During the Polish-Soviet War (1919–1921) Merian C. Cooper served in the Polish Air Force and organized the Eskadra Kościuszkowska (Kościuszko Squadron); then after being captured by the Soviets, he escaped from a prison near Moscow and reached the Latvian border on foot.”

Although the story of Towhead seems to be a fantastic adventure story, from the perspective of Słomczyński’s experience, it is not so unreal; ancient and mythical adversities do not look more dangerous or impossible than his family’s survival during the 20th century. Due to this, myths become a clue for understanding, overcoming and retelling a personal and family history and a way of dealing with the personal trauma of war and a rather violent peacetime.

* For a more detailed description, see the article by Robert A. Sucharski, “Joe Alex (Maciej Słomczyński) and His Czarne okręty [Black Ships]: A History of a Trojan Boy in Times of the Minoan Thalassocracy,” in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Hope: The Ancient Myths as Medicine for the Hardships of Life in Children’s and Young Adults’ Culture, Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2021, 215.

** R. Sucharski, “Joe Alex (Maciej Słomczyński) and His Czarne okręty [Black Ships],” 215–216.

Further Reading

Sucharski, Robert, "Joe Alex (Maciej Słomczyński) and His Czarne Okręty [Black Ships]: A History of a Trojan Boy in Times of the Minoan Thalassocracy", in Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Our Mythical Hope. The Ancient Myths as Medicine for the Hardships of Life in Children's and Young Adults' culture, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2021, 211–218.