Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Simon Spence, Odysseus. Early Greek Myths (Series, Book 3), Createspace (Independent Publishing Platform), 2016, 36 pp.

ISBN

Official Website

earlymyths.com (accessed: July 31, 2018)

Genre

Illustrated works

Myths

Retelling of myths*

Target Audience

Children (c. 3-8)

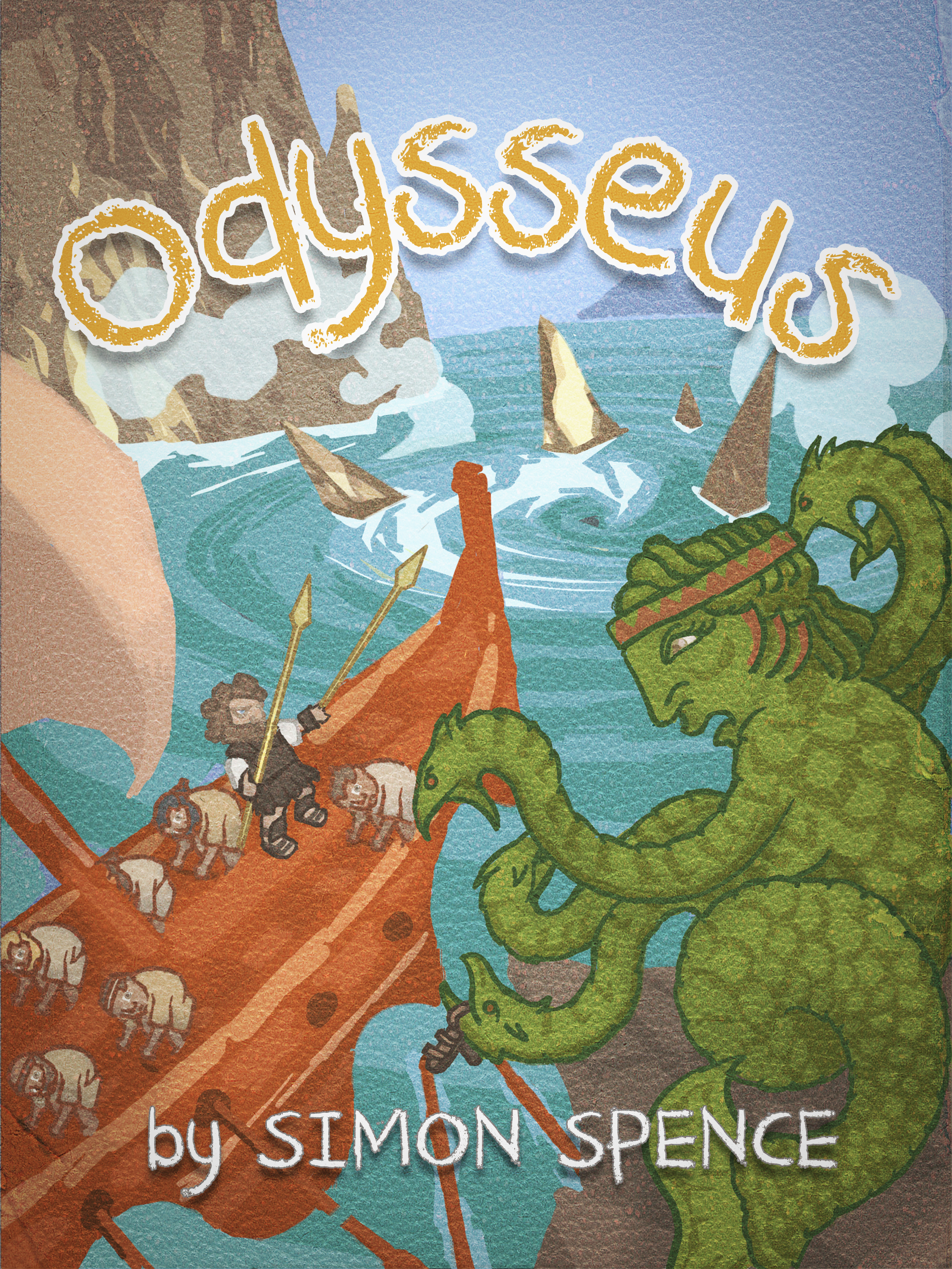

Cover

Courtesy of Simon Spence.

Author of the Entry:

Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Portrait, courtesy of the Author.

Simon Spence (Author)

Simon Spence studied at University College Dublin before completing a PhD at the University of Nottingham. An adapted version of his PhD thesis is available as The Image of Jason in Early Greek Myth:An Examination of Iconographical and Literary Evidence of the Myth of Jason Up Until the End of the Fifth Century B.C. (self-published via Createspace, 2010). Simon Spence launched the Early Myths series in 2013.

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Next book: Atalanta.

Summary

This is a retelling of Homer's Odyssey with myths based on the Epic Cycle used for additional material. The narrative order of the Odyssey is rejected in favour of a chronological approach. Most of the gods are helpful in this retelling. The "sea-god" alone persecutes Odysseus, and as Odysseus is not shown to be responsible for what incurred the sea-god's wrath, Odysseus appears a highly sympathetic figure. The story includes violence, but extreme violence and sex are avoided to suit a young reader or listener. The book has been published through Createspace, Amazon's self-publishing platform. The spine of the book is more pamphlet-style than typical book style, but nonetheless, the quality of the book's production is in-keeping with more conventionally published works, with attractive full-page colour illustrations and well-laid-out text. An information section, "Some interesting notes for grown-ups" accompanies the work at the back of the book.

Analysis

The story opens with Odysseus and Penelope living happily with their new baby, Telemachus. Their life is disturbed when 'the wife of one of [Odysseus'] friends' is "stolen away" and he is called on to help "rescue her." This interpretation of this flashpoint in the Trojan War myth avoids placing emphasis or blame on Helen, preferring to retain the focus on Odysseus. The goddess Athena, who "looked after Odysseus," witnesses his pretence at madness, but does not otherwise intervene in this section; as such, the reader is familiarised with Athena's presence into the story very early on, before she has started to play a part. This helps to establish the story as a fantastical one.

The Trojan War is addressed in the next page-section. The emphasis is on the Wooden Horse trick. The Greeks successfully entry Troy and extricate Helen, but there is no reference to the fall of Troy as such, thus muting the violence for a young audience. The illustration of the Trojan Horse is based on the horse used in the film, Troy (dir. Wolfgang Petersen, 2004).

The story then progresses with a section on the Cyclops. The Cyclops' monstrosity is described; he is a "giant with only one eye" and Odysseus has the impression that the Cyclops may eat them (a softening of the events in Homer's Odyssey, where several of Odysseus' crew are eaten). There is no reference to Poseidon or Odysseus' boasting; the emphasis falls on Odysseus' clever escape plan. This removes the traditional focus on Odysseus' moral lesson (that he should be more cautious) but conveys a learning point that is perhaps more relevant to young readers, namely the importance of using intelligence to solve problems - a learning point that is still very in-keeping with Odysseus' character. Next, come Aeolus and the bag of winds. As there had been no divine punishment after the Cyclops episode, the crew appear to bear a greater share of the blame for the ship's troubles when Aeolus' winds blow them off course. Circe and the metamorphosis of the crew follow. Athena assists Odysseus where the Odyssey has Hermes, a simplification that enables young readers to keep track more easily of the cast of characters and their roles. The Sirens appear next, depicted as eagles with the heads of young blonde women. Scylla and Charybdis follow, with Scylla depicted as a green-scaled monster with one humanoid head and several snake-like heads. The Cattle of the Sun episode (Odyssey, 1.8; 11.104–115; 12.128–141, 320–450) is dealt with as the crew stealing "some food from the island of the great god of the sea." The god sends a storm in revenge and "the men were washed away." The change of a god simplifies the narrative to connect crime and punishment. The reference to the men's fate is vague enough to suggest peril without details that might be considered too disturbing for young children. Similarly, there is no visit to the Underworld, an episode which some might well consider unnecessarily challenging material for the target audience of this series.

Calypso is presented comforting Odysseus and providing him with food and drink. Her sexual interest in him is avoided, as is the sense of her holding him captive. When Hermes arrives, Calypso is told to help Odysseus and Odysseus is told that it is time to "start his journey" home. Again, this offers the essentials of the story while softening the content. The accompanying illustration hints at sterner stuff; Hermes appears angry and commanding as if rebuking Calypso (and possibly Odysseus) while pointing towards Odysseus' departure.

A variety of skin tones are used throughout the work. Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus are all blue-eyed; Odysseus brown haired; Penelope blonde. Athena, Circe, the Sirens, and Calypso are all blue-eyed. Nausicaa and the Phaeacian episode follow Calypso's island. Nausicaa is depicted as quite dark brown-skinned, and she and her handmaidens have black hair. Nonetheless, Nausicaa and the handmaidens are all blue-eyed, and the king and queen are depicted as very fair-skinned in contrast to their daughter. While the inclusion of varied skin-tones gives the impression of a Mediterranean environment, with Phaeacia indicated as a possibly North African location, the blue-eyed blonde theme associates the story with a more traditionally Northern European context.

The reader learns that Odysseus is stranded on this new land because "the sea-god sent a second terrible storm!" A page is devoted to Nausicaa discovering Odysseus. Her bravery is praised. She is described as doing laundry, but the Odyssey's account of Athena prompting Nausicaa's outing is not included. Athena presides over the meeting scene in the illustration. This lends the impression of her concern for Odysseus without drawing her explicitly into the narrative. A second page is devoted to Odysseus' time with Alcinous.

A page-section then introduces the situation on Ithaca. The dog, Argus, is mentioned as the only one to recognise Odysseus ("Shush Argus"); the dog's death is omitted. Penelope's trick then features in its own page; she is weaving a "blanket" rather than a shroud, avoiding a vocabulary term likely to be unfamiliar to a young audience, and its connection to death. Athena is depicted looking on smilingly as Odysseus turns on the Suitors following the competition with the great bow. Odysseus fires arrows at them, "clearing them from him home," – an account which communicates the gist of the events without the violent detail.

In the final page-section, Penelope performs the bed check to confirm Odysseus' identity, and Odysseus and Telemachus go to meet Laertes. The final illustration depicts Odysseus and Laertes greeting each other, with Telemachus and Penelope looking on, and Athena in the background. "Finally the whole family were together once more." The ending stresses the importance of homecoming that is so fundamental to the Odyssey, avoiding the unsettling open-endedness of the winnowing fan prophecy.

The book is laid out so that each pair of pages comprises one fully illustrated page and one pure text page, making the visual style of the book a dominant part of the overall impression of the work. The illustration style places the events in antiquity throughout, with tunics, spears, ancient style ships and similar physical indicators of antiquity. The figures are nonetheless stylised, appearing in a cartoonish naïve style that renders them childlike and unthreatening. There is some very beautiful and creative use of texture to render the natural environment in which the characters move. There is a "notes for grown-ups" section at the end, which explains that there are many versions of the myths in the story and that this book is based "on the oldest parts and focus on sources from 1000–400BCE." The inspiration behind some of the illustrations is explained. A vase depicting an archer is cited as an inspiration for the illustration of Odysseus and the Suitors; a vase of Odysseus and Nausicaa is then demonstrated to be the source of their discovery scene. The famous British Museum Siren Vase (accessed: 8.10.2020) is discussed as the inspiration for that scene, although there is no discussion of why the Sirens' heads were done so differently to the vase Sirens when their bodies were rendered so similarly. Mosaic floors appear in illustrations throughout the book, while the palace on Phaeacia has been depicted in the manner of a Mycenaean palace complete with pillars and a large frieze.

The series website (accessed: 31.07. 2018) places significant emphasis on using the "oldest strands of the tales" and "original art such as surviving Greek vase paintings"; explaining that "The reason we go back so far is to try to find the original tale, the less spoilt version. There is something purer and more refined about these versions." This indicates that there was a specific, even ideological, approach at work in how the traditions were selected, with a clear message privileging the oldest traditions and a suggestion of corruption in later versions. The strong assertion of the ancientness of the source material is slightly belied by, for example, the decision to depict the Trojan Horse after the Troy (2004) horse, although the image works well.

Further Reading

Eisenberg, William D., "Morals, Morals Everywhere: Values in Children's Fiction", The Elementary School Journal 72.2 (1971): 76–80.

Miles, Geoffrey, "Chasing Odysseus in Twenty-First Century Children’s Fiction", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature. Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Murnaghan, Sheila, "Men into Pigs: Circe’s Transformations in Versions ofThe Odyssey for Children", in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature. Heroes and Eagles, Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Roisman, Hanna M., "The Odyssey from Homer to NBC: The Cyclops and the Gods", in Lorna Hardwick, Christopher Stray, eds., A Companion to Classical Receptions, London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

The University of Chicago Library, 'The Children's Homer', part of Homer in Print: The Transmission and Reception of Homer's Works available at lib.uchicago.edu (accessed: July 31, 2018).