Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Nikos Kazantzakis, Μέγας Αλέξανδρος [Mégas Aléxandros]. Athens: Eleni Kazantzakis, 1978, 330 pp.

First published as Στα Χρόνια του Μεγαλέξανδρου [Sta chrónia tou Megaléxandrou] in serial form in Neoloaia magazine, issues 19 (10.2.1940) to 52 (28.9.1941), unfinished.

ISBN

Genre

Didactic fiction

Historical fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Anastasia Bakogianni, Massey University, a.bakogianni@massey.ac.nz

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

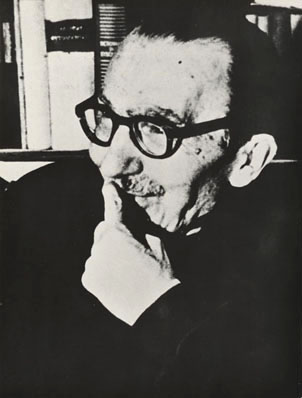

Nikos Kazantzakis, picture from Wikipedia Commons: Original at the Kazantzakis Museum [CC BY 3.0] (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Nikos Kazantzakis

, 1883 - 1957

(Author)

Nikos Kazantzakis was a Greek writer, playwright, essayist, translator and philosopher, perhaps best known for his novels The Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas (1946) and The Last Temptation (1955), both of which were made into films (as Zorba the Greek in 1964 and The Last Temptation of Christ in 1988). Born in Heraklion, Crete Kazantzakis enjoyed a life-long relationship with ancient Greece, which is strongly reflected in his oeuvre. His most important poem, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel (1938) is a love-letter to Homer in which Kazantzakis explored his own philosophical ideas. The ancient epic hero also features in his early play From Odysseus, A Drama (1922, 1928 and rev. 1955).

Sources:

The website of the Historical Museum of Crete (accessed: June 28, 2018).

The website of the Nikos Kazantzakis Museum in Myrtia, Crete (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Anastasia Bakogianni, Massey University, a.bakogianni@massey.ac.nz

Translation

English: Alexander the Great: A Novel, trans. Theodora Vasils, Ohio University Press, 1982 (see here, accessed: July 20, 2018).

Spanish: Alejandro el Grande, trans. Mirta Arlt, Carlos Lohlé, 1983.

Ukrainian: У Кноському палаці. Александр Македонський [U Knos'komu palat͡si. Aleksandr Makedonskyĭ], trans. Vasily Stepanenko (1) and Tetyana Chernishova (2), Kyiv: Vydavnyt͡stvo Dyti͡achoi Literatury „Veselka”, 1986.

Italian: Alessandro Magno: Romanzo storico per ragazzi, trans. Vittorio Volpi, Biblioteca Comunale, 1998.

German: Alexander der Große, trans. Andreas Krause, Verlag der Griechenland Zeitung, 2015.

Bulgarian: Александър Велики [Aleksand''r Veliki], trans. Драгомира Вълчева Dragomira V''lcheva, Siela, 2019.

Summary

The novel covers Alexander the Great’s life, beginning with his famous taming of the wild horse Bucephalas at fifteen and ending with his death in Babylon in 323 BCE. The novel focuses primarily on Alexander’s twin ambitions, to unite Greece and to conquer Asia and how he made them a reality. He shared these aspirations with his father Philip II of Macedon, who is an important character in the early part of the book. This covers Alexander’s early life at his father’s court, and his training as general fighting in Philip’s campaigns to unite the Greeks. After the king’s assassination, Kazantzakis retells in an entertaining manner the thrilling story of Alexander’s conquests and famous victories that we are familiar with from our ancient sources, written centuries after the events themselves. Kazantzakis lends the legend of Alexander the Great’s life a modern-Greek twist for his young readers.

Analysis

This is a ‘boys’ own adventure’ retelling of the life of Alexander the Great, written with a young readership specifically in mind. Kazantzakis opens up a window onto the life and times of Alexander, as seen through the eyes of a younger boy in his service, Stephan. He acts as the reader’s lens onto historical events, especially in the opening chapters. Stephan’s engaging voice helps to draw in young readers, who can more easily identify with his point of view, rather than that of the legendary Alexander. But, Stephan hero-worships Alexander and this also colours the reader’s outlook. The novel is specifically tailored for young boys, an exciting tale of derring-do and grand adventure. There are not many female voices, apart from Alka, who is Stephan’s friend and romantic interest, and his loving mother Elpinice. She is referred to as "Kyra" Elpinice, one of the many modern Greek touches in the novel. We also catch a glimpse of Olympias, Alexander’s mother, defined in terms of her relationship to her famous son and her ambitions for him, which is typical of the portrayal of female characters in novels that foreground the male perspective.

The novel has a clear didactic purpose, Kazantzakis’s aim to educate his young readers about ancient Greek history and the life and times of Alexander in particular. The novel also contains information about earlier key historical events, ancient Greek literature, as well as ancient Greek practices and customs. This emphasis is designed to cultivate a sense of national pride during a time of crisis for Greece. But Kazantzakis goes beyond a simple retelling of historical events. The story of Alexander’s life is recounted in an engaging manner, with Stephan’s point of view as one of its main anchors, although there are also a number of authorial interventions in the novel. The author skilfully employs the plural ‘we’/’our’ to involve and instruct his readers and to inspire a new generation with Alexander’s example. Kazantzakis seeks to demonstrate to his young readers the qualities that are important in this life. He sets up Alexander, and his close circle of friends, as examples for emulation, showing his young male readers how they, too, could grow up to be good and worthy men in the service of their families, ancestors and of their country.

There is a strong vein of Helleno-centrism in the novel, Kazantzakis uses Alexander’s example to instil a deep love for their country in his young readers. Taking into account the date the novel first appeared in serialised form (February of 1940 to the end of September 1941), this emphasis was highly topical, indeed urgent. The novel’s serialisation coincided with the turbulent period when Greece entered World War II, including the preliminaries when it came under increasing pressure to pick a side in the conflict engulfing Europe, the Greco-Italian war which begun in October 1940 and the Nazi invasion of April 1941. The fact that the serialisation was never completed suggests that Kazantzakis’ message and its topical analogies proved all-too transparent. Philip II and Alexander’s calls for Greek unity in the face of a foreign enemy in the novel can easily be mapped onto the situation facing Greece in the beginning of the 1940s. Kazantzakis never had the chance to revise the novel, which was published posthumously in 1978, so its episodic nature can still be detected.

In the novel, Alexander is portrayed as an extraordinary Greek, who brought the light of Greek civilization to Asia and even parts of India. Kazantzakis’ Alexander makes it clear that one of the main reasons for his attack on Persia was his burning desire to avenge Greece’s suffering during the Persian invasions of the fifth century. The campaigns of Alexander are thus not simply fuelled by an insatiable ambition, which Kazantzakis acknowledges, but also by sound reasoning, endorsed by no less a figure than Aristotle, the famous ancient Greek philosopher and the young prince’s tutor. Alexander’s conquests are thus portrayed as a highpoint in Greek history that modern Greeks should remember with pride. Alexander’s focus, his strategic and tactical skills, his ability to endure hardship, his deep respect for his ancestors, his love of his friends and his punishment of his enemies are qualities and characteristics that Kazantzakis sets up as worthy of emulation. His less desirable qualities such as his temper, arrogance, and his overweening ambition are still present, but Kazantzakis downplays them. His Alexander is fallible, but, on balance, a great Greek hero whom he sets on a pedestal.

In contrast to the Greek protagonists of the novel, the Persians are presented in a negative light. Readers’ first encounter with Persia is with its ambassadors at Philip’s court, who conspire to kill Alexander and his father. But they bribe lowly minions to take all the risks rather than openly opposing the Macedonian royals. Later in the novel, King Darius III’s arrogance is matched only by his lack of courage in the face of danger. He runs away from Alexander cowed according to Kazantzakis by his Greek opponent’s charisma and his many successes in battle. The emphasis on Greek freedom versus Persian tyranny dates back to Herodotus and his History of the Persian Wars, but within the novel’s 1940s context it becomes highly relevant. In the final stages of the novel, Kazantzakis offers a largely positive take on Alexander’s wish to integrate the Persians into the Greek system and downplays Greek opposition to his plans.

Kazantzakis does not offer his readers lengthy descriptions of famous ancient battles, rather he imitates Homer by focusing on individuals and their daring acts of heroism. A notable example being a night-mission involving Stephan and some of his close friends to steal a specially armoured Persian chariot and bring it back to the Greek camp to be examined. This episode exemplifies Kazantzakis’ skilful marriage of fact and fiction. The story is in line with Alexander’s well-known strategy of intelligence gathering prior to engaging his enemies in battle. The focus in the novel, as in our ancient sources (Arrian, Plutarch, Diodorus Siculus, Pseudo-Callisthenes) and their countless subsequent imitators, is Alexander himself. The narrative device of telling part of the story from Stephan’s view brings the legend closer to his intended audience, but cannot entirely bridge the divide. Kazantzakis does offer his readers a fast-paced, exciting and engaging narrative that skillfully blends history and fiction, but his Alexander remains at a ‘Homeric’ distance, a legend from the classical age like the heroes he claimed descent from, Achilles and Hercules.

The author glosses over some of the darker episodes in Alexander’s life, like his fraught relationship with his father, which is downplayed in the novel and his murder of his friend Cleitos the Black in a drunken rage. Kazantzakis emphasises Alexander’s remorse and shows him attempting to kill himself out of guilt. He is prevented by his friends. Even at the end, when Alexander’s troops rebel and force him to turn back, Kazantzakis maintains an upbeat tone. His Alexander continues to make plans for further military and naval adventures and manages to win back the love and respect of his soldiers. By ending the novel when Alexander closes his eyes for the last time Kazantzakis also avoids having to deal with the much less inspirational history of the power struggles of Alexander’s successors. The wars of the Diadochi are foreshadowed in the novel during a conversation between Alexander and his admiral Niarchos. Alexander worries about the fate of his empire and gives voice to his fear that everything he has created will fall apart after his death. But by ending the story with Alexander’s death Kazantzakis focuses his reader’s attention on his exceptional life of achievement and its legacy as an exemplar for his young readers who he hopes will become modern Alexanders in Greece’ hour of need.

Addenda

Published posthumously by his wife Helen N. Kazantzaki.

In preparing this entry I consulted the Greek second edition of the novel (1983), which I first read as a child and Theodora Vasils’ English translation (1982).