Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Regulus, an episode in a collection of school stories, first published in Nash's Magazine, Pall Mall and Metropolitan Magazine in April 1917, later the same year in the collection A Diversity of Creatures.

ISBN

Available Onllne

Full e-text of the story available at online-literature.com or ebooks.adelaide.edu.au (accessed: August 3, 2018). A LibriVox recording (read by Tim Bulkeley, posted Aug. 20, 2011) is free to download (length 53:37) at librivox.org (accessed: August 3, 2018).

Genre

Fiction

School story*

Short stories

Target Audience

Crossover (Teenagers and Young adults)

Cover

The cover of The Complete Stalky & Co, publ. in Oxford World’s Classics (Oxford University Press, 1999) as a reprint of World’s Classics paperback with Introduction, Note on the Text, and Explanatory Notes by Isabel Quigly; General Preface, Select Bibliography, and Chronology by Andrew Rutherford published in 1987. Detail from Three Young Cricketers, c. 1883, by George Elgar Hicks, Southampton City Art Gallery/ Bridgeman Art Library. Picture is in the public domain for non commercial use.

Author of the Entry:

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

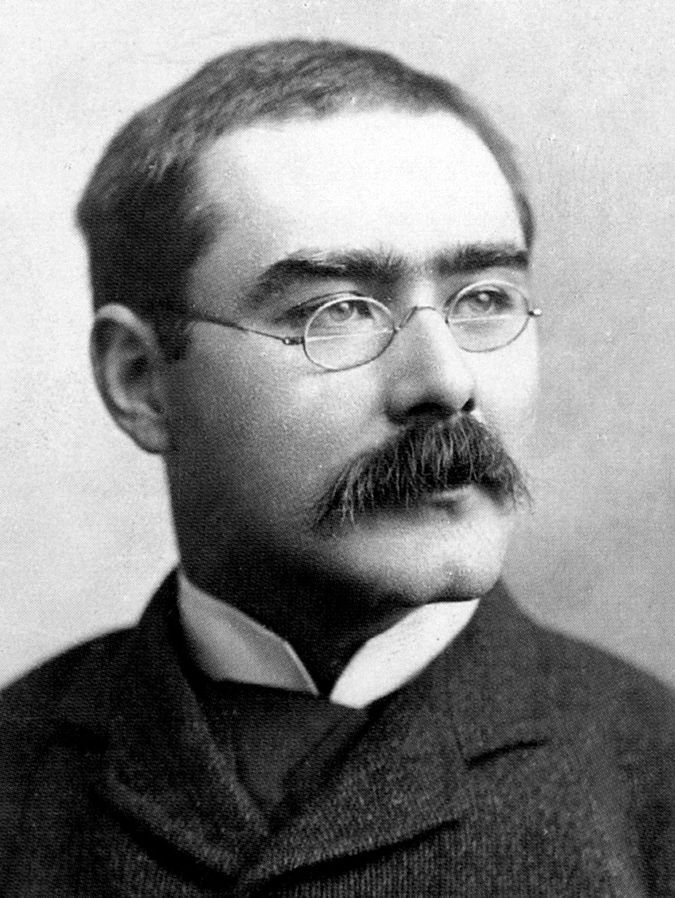

Kipling’s portrait is in public domain; it was used as frontispiece to the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer, first published in New York by Henry Holt and Co. in 1915; the full text of the biography available here (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Joseph Rudyard Kipling

, 1865 - 1936

(Author)

Born in Bombay, India, educated in England at the United Services College in Westward Ho! At the age sixteen he returned to India, to Lahore where his parents then lived, to work as journalist in local English newspapers and write poems and short stories. After seven years, he was back in England already as a successful writer. Married an American, Caroline Balestier, in 1892, travelled with her extensively and then settled in Brattleboro, Vermont, where his two daughters were born and he continued writing there (among others The Jungle Books). After the birth of his daughter Josephine in 1892, Kipling started writing for children. In 1896, the Kiplings went back to England and lived in Rottingdean, Sussex. Their son was born in 1897; Josephine died in 1899 during a family trip to America. Kipling’s fame was already well established in English speaking countries and beyond. In 1902, seeking a quieter life, they moved to the Bateman’s, a country house in Sussex. In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. His son John died early during WW1 (1915) and Kipling became active in the Imperial War Graves Commission striking a close friendship with King George V. He died in 1936, his autobiography written in 1935, Something of Myself, was published posthumously by his widow; she died in 1940.

Sources:

The Kipling Society's website (accessed: June 28, 2018).

The Kipling Society lists at their site 14 Kipling’s biographies publ. between 1930 and 1999 (accessed: June 28, 2018); see also Winston Churchill’s Great Contemporaries, ed. by James W. Muller. Ed. pr. London: Butterworth, 1937 (Wilmington, Delaware: ISI Books, 2012) 418–424.

Profile at the BBC website (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Profile at the Nobelprize.com (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Bio prepared by Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Adaptations

Stalky & Co. was used as basis for a six-part BBC television series, produced in 1982 by Barry Letts and directed by Rodney Bennett, both Doctor Who veterans; script-writer was Alexander Baron. It featured An unsavoury Interlude, The Ambush, Slaves of the Lamp, The Moral Reformers, A Little Prep, and The Last Term, it did not include Regulus.

Translation

The whole collection translated into many languages but Regulus probably because it was originally published as part of A Diversity of Creatures appears to have been translated, as far as I was able to determine, only into German, by Gisbert Haefs in 1988 (Haffmans Verlag); he produced a revised translation in 2016 (S. Fischer Verlag).

Summary

An introductory note preceding the story explains that the Roman general Regulus, about whom Horace wrote the Ode 3, 5, was captured by Carthaginians and then sent to Rome to negotiate on their behalf. Regulus convinced the Senate not to negotiate with his captors, knowing well that in retaliation, they would torture and kill him.

At United Services College in Westward Ho!, the Latin teacher Mr. King asks Fifth Form students to prepare for the entry exam to military colleges to translate the ode line-by-line. The translation advances laboriously, punctuated by Mr. King’s sarcastic comments and disparaging remarks about his students’ ignorance and lack of discernment. The quality of the translation varies distinctly from student to student and provides a review of typical high school offerings, from acceptable to absurd and risible. In the science lab next door, a bottle of chlorine breaks once again and the acrid smell interrupts the class. Mr. King comments on the need to be tolerant towards the so-called Moderns at which a student quotes a recently read line from Horace’s Ode 3, 10 about the limits of tolerance. Coming out of the Latin class, students joke among themselves and, to make points, quote suitable lines from Horace.

During the next class – mechanical drawing – “Pater” Winton, one of the responsible Fifth Form students acts out of character, and lets loose a mouse creating total confusion. His silly prank results in detention and punishment consisting of writing 500 lines in Latin which makes him miss rugby practice – a transgression automatically punishable by flogging administered by the Captain of Games. Winton apologizes to the drawing master for the prank but does not want him to call off the punishment which he considers to be just. Mr. King helps Winton by dictating to him a portion of the Latin lines. He then leaves to take tea with the science master Mr. Hartopp. Winton goes to his form room to finish the lines but students coming back from rugby practice annoyingly commiserate with his predicament and make him lose his temper to the point of physically attacking a particularly insensitive boy. The fight is joined by other boys; when the two teachers, King and Hartopp, enter the room, King comments using Horatian quotations and, to his delight, is answered in kind by Stalky. The teachers leave and the boys manage to overpower Winton who comes to his senses, devastated by his outburst. Stalky and a few other students take Winton to Number Five Study to clean up, treat injuries, and rest with a cup of cocoa. The teachers observe them unseen and continue their discussion on the humanities and sciences and their relative importance in education, reviewing the standard arguments. At the Number Five Study, the boys discuss the events and decide that Winton should quickly go to Mullins, the Captain of Games to get it over with. Mullins is almost finished dispensing perfunctory punishment to younger boys who were absent at practice, he uses his cane but without malice. When Winton reports for his judgment, it is rendered with minimum fuss; his relief is so great that he falls asleep immediately after, on the window sill. The Head of the Coll. asks Mullins to reassure poor Winton who is anxious about other possible consequences of his behaviour; Mr. King promotes Winton to sub-prefect for showing character. The two teachers with the Reverend John, the chaplain, continue the Classics versus Modern debate until 10 pm. They hear Stalky coming back after evening study, calling Mullins barbarus tortor and saying to Winton Night, Regulus. Mr. King marvels at how students absorb and appropriate classics.

Analysis

Regulus is a pure delight for anybody who ever studied Latin at school. The way the class is conducted: a bored and disdainful teacher does not expect anything good from his students and reacts sarcastically to every one of the many mistakes they make in translating the ancient text. The teaching method is traditional and old fashioned. A text is assigned and students are supposed to have translated it as homework. In class, the teacher asks one student after another to translated a fragment. The command of Latin in the class is weak on average. Usually, a better-prepared student guides his friends and helps them to prepare for the class. The teacher criticizes their efforts without pity. The tension is high, it lowers when the next victim is selected and rises again before the teacher asks another student to continue translation. Occasionally, the teacher adds an illuminating comment or a digression, enjoyed by the whole class. Those who had Latin at school have all been there and easily relate to Kipling’s narrative.

The pains of learning Latin are only one aspect of the story. In this highly amusing school story, Kipling shares his belief that once the barrier of a difficult language is broken, the content of the ancient text reaches the minds and souls of students. Reading about Roman virtues and people who lived their lives according to them, prepares them for challenges in their own lives, and in this particular case, the challenges of serving the empire and fighting for it. The reception of Roman virtues in the education of the empire is shown as an important ideological factor for the era of the expansion of British rule. Regulus presents also, again in a manner charged with humour, the conflict between two different educational priorities, Classics versus Moderns. The industrial revolution required scientific progress and teaching of science, Kipling offers in Regulus a rationale for keeping classics as part of education as an ideologically and intellectually important element leading to exemplary civil and military service. The argument for teaching classics evolves from period to period, the one presented so brilliantly by Kipling reflects the mindset of over a century ago.

Further Reading

Acheraïou, Amar, “Kipling and imperial Rome. The warrior ideal in Regulus”, in Rethinking Postcolonialism. Colonial Discourse in Modern Literatures and the Legacy of Classical Writers, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, 19–24.

Axer, Jerzy, “A Latin Lesson for Bad Boys, or Kipling’s Tale of the Enchanted Bird”, in Our Mythical Childhood… The Classics and Literature for Children and Young Adults, Katarzyna Marciniak, ed., Leiden – Boston: Brill, 2016, 55–64.

Hagerman, Christopher A., Britain's Imperial Muse. The Classics, Imperialism, and the Indian Empire, 1784–1914, Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Leary, T. J., "Kipling, Stalky, Regulus & Co.: A Reading of Horace Odes 3.5.", Greece & Rome 55, 2 (2008): 247–262.

Lucht, Bente, Writing Empire: Latin Quotations in Texts on the British Empire, (Heidelberg: Winter, 2012). Anglistische Forschungen 425. See in particular chapters: “Rudyard Kipling. Kipling's Regulus: Horace's Regulus and Kipling's Regulus,” “Translatio(n) in Kipling's Regulus,” “A translation - Horace, Bk. V, Ode 3.”

McDermott, Emily A., “Playing for His Side: Kipling’s Regulus, Corporal Punishment, and Classical Education”, International Journal for the Classical Tradition 15, 3 (2008): 369–392.

Nagai, Kaori, “Quotations and Boundaries: Stalky & Co.”, in Jan Montefiore, ed., In Time's Eye: Essays on Rudyard Kipling, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013, 207–224.

Plotz, Judith A., “Latin for Empire: Kipling's Regulus as a Classics Class for the Ruling Classes,” The Lion and the Unicorn 17.2 (1993): 152–167.

Treggiari, Susan, “Kipling and the Classical World”, June 22, 2012 available at kiplingsociety.co.uk (accessed: August 3, 2018).

Addenda

Regulus, an episode in a collection of school stories, first published in Nash's Magazine, Pall Mall and Metropolitan Magazine in April 1917, later the same year in the collection A Diversity of Creatures; in 1929 Regulus was integrated into The Complete Stalky & Co.

Regulus paired with An English School (an autobiographical short story publ. in 1893 in the magazine The Youth’s Companion and in 1923 in the collection Land and Sea Tales) was published in 2010 by Viewforth Press (Los Angeles) with a short introduction by Craig Paterson.