Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Jean Paul Mongin, La mort du divin Socrate, Les Petits Platons. Paris: Diaphanes Verlag, 2010, 63 pp. [French language version]

Jean Paul Mongin, The Death of Socrates, Plato & Co., trans. Anna Street. Zurich-Berlin: Diaphanes Verlag, 2010, 63 pp. [English language translation]

ISBN

Genre

Biographies

Illustrated works

Philosophical fiction

Picture books

Target Audience

Crossover (Teens, Adults)

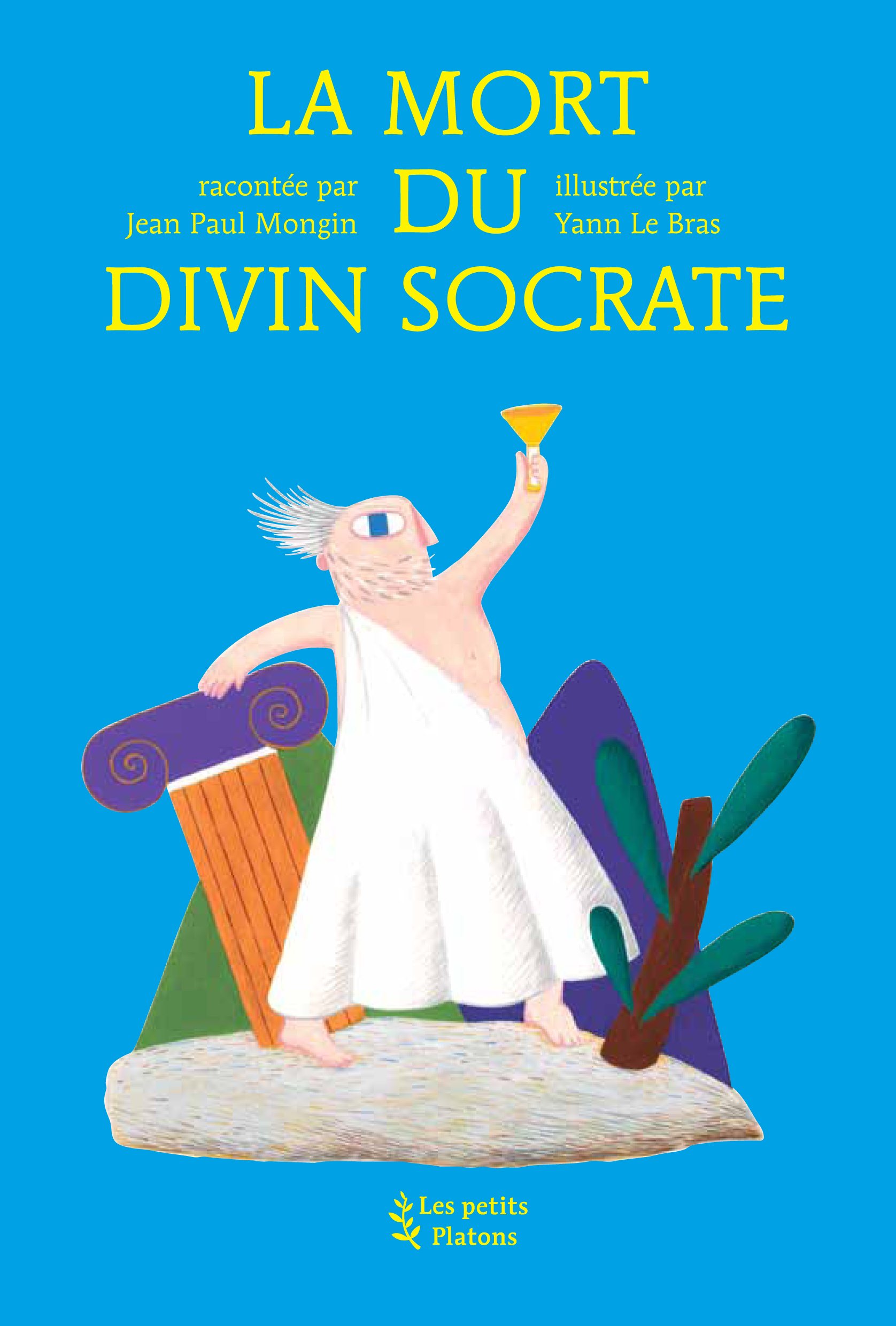

Cover

Cover of the French edition. Courtesy of the Publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy, University of Roehampton, s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Yann Le Bras (Illustrator)

Yann Le Bras is an illustrator based in Strasbourg, France. He studied visual arts at Rennes II University. He now works as an illustrator with the educational department of the Tomi Ungerer Museum. The first book illustrated by Yann Le Bras was La Mort du Divin Socrate (The Death of Divine Socrates, 2010). Among his later works are Le roi Midas et ses oreilles d’âne (Midas the King and His Donkey Ears, 2012), Socrate sort de l’Ombre (Socrates steps out of the Shadow, 2012), and Socrate Président ! (Socrates the President !, 2017).

Source:

Official website (accessed: December 2, 2021).

lespetitsplatons.com (accessed: December 2, 2021).

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk and Angelina Gerus, University of Warsaw, angelina.gerus@gmail.com

Courtesy of the Author.

Jean Paul Mongin

, b. 1979

(Author)

Jean Paul Mongin is a philosopher who lives and works in Paris, in France. He studied philosophy at the Sorbonne before joining the army and then working in a number of industries. He returned to philosophy as the creator of the Petits Platons series which offers an informal and highly illustrated introduction to the works of a number of philosophers. Other titles in the series include Professor Kant's Incredible Day (2016) and Hannah Arendt's Little Theater (2016). Jean Paul Mongin runs philosophy workshops for young people aged 8 to 15 years in which they are encouraged to discuss the ideas in the Petits Platons publications.

Bio prepared by Sonya Nevin, University of Roehampton, sonya.nevin@roehampton.ac.uk

Translation

German: Der Tod Des Weisen Sokrates, trans. Heinz Jatho and Sabine Schulz, Zurich-Berlin: Diaphanes Verlag, 2014.

English: The Death of Socrates, trans. Anna Street, Zurich-Berlin: Diaphanes Verlag, 2015.

Summary

The Plato and Co. publications explore the lives and works of ancient and modern philosophers in highly illustrated slim volumes. This contribution to the series addresses the trial and subsequent death of Socrates following Plato's account and in doing so presents a number of Socrates' ideas as a narrative of this period of his life.

The Death of Socrates opens with an enquiry, apparently from the narrator, to the Delphic Oracle as to who is the wisest man in Greece. The oracle answers that Socrates is, for he "is love with the truth" (p. 5). There follows an account of Socrates' practice of questioning people to discover what they know and how they know it. Many people run away from Socrates' questions while others become angry and resentful. Some "decide to take legal proceedings against him" (p. 9) accusing him of corrupting the young and failing to honour the gods. Over ten pages Socrates defends himself, observing how he has been misrepresented, how he cannot be guilty of both introducing new gods and of disbelieving in gods, and how he has striven to improve the moral, philosophical health of the Athenians. He reminds the court of his defence of the law during his presidency over the Council during the crisis following the Battle of Arginusae. Socrates is found guilty. His accusers call for the death penalty; he counters not with an appeal for clemency but with an assertion that the city should honour him for his service. Socrates is condemned to death.

The next phase of the book is set in prison and is concerned with Socrates' discussions of death and with the manner of his death. He reminds his followers that death should not be feared as its conditions are unknown; it could be "a marvellous gain" (p. 22). The date of Socrates' death is delayed by a festival, the city's celebration of Theseus' defeat of the Minotaur. Socrates and his friend Crito discuss a dream that Socrates has had which seems to anticipate that his death will take place in three days' time. Crito urges escape, but Socrates insists that he is committed to a life of justice that is incompatible with flight from the law. In three days' time, the festival comes to an end and Socrates' execution is scheduled.

Socrates is visited by all of his best friends, except Plato, who is ill. Socrates' wife, Xanthippe, and their children visit him in prison. He talks once more to his friends about the uncertainty of the nature of the Afterlife, and of the potential good to be gained from the psyche's separation from the body. Psyches are depicted as single colourful butterfly-wings led by semi-grotesque humanoid daimons. Socrates describes how little humans really know of their own existence and speculates on the greater understanding that death may bring. He describes the prospect of people's personal daimons leading them to the Underworld and their psyches' immersion in the rivers of Hades or their introduction to beautiful dwellings. Socrates is calm but his friends are distressed. They ask what he wishes for after his death and he instructs them to live well. He meets with his sons once again and gives the older ones instructions. Socrates then sends his children away and drinks the poison that has been prepared for him. As the poison reaches its final stage, Socrates reminds Crito to sacrifice to the god of medicine, Asclepius, and with that he dies. The illustration shows sunlight filling the sky and Socrates' daimon carrying his psyche over the horizon.

Analysis

On a background of bright blue, cartoon Socrates holds aloft a cup whilst standing before a jaunty-angled Ionic pillar picked out in dark blue and orange. The death of Socrates has never seemed so bright and accessible a topic as is does on this the cover of Mongin's work. The simple narrative and plentiful illustrations make this an accessible read about a challenging topic. The author has drawn directly on Plato's works on this subject (Apology; Crito; Phaedo; and to a lesser extent, Euthyphro). By opening with the Delphic Oracle's praise of Socrates (Plato, Apology, 20e), the reader is encouraged to sympathise with him from the start even if his fame were not enough inducement. The summarised, sometimes paraphrased, elements of Plato's Apology which follow then enable the attentive reader to understand Socrates' approach to seeking truth as well as his defence. In this sense, like the ancient source material, this work is an example of Socrates' method of philosophy as well as an account of his trial and death. This approach is repeated in the latter sections of the book in which the paraphrased version of Socrates' conversation as put forward by Plato demonstrates how one might usefully approach thinking about death and the unknown as well as providing an account of Socrates' last days.

The book's illustrations depict the events happening in the main narrative (such as Socrates talking with friends) and more abstract ideas mentioned in Socrates' conversation (such as Socrates as a gad-fly or, more surreally, Socrates' vision of souls in the Underworld). The images are rendered in a faux-naïve style which mostly features simple cartoon figures with very large eyes and simplified figures shown against colourful background architecture. Some of the more surreal images of souls and their daimons are still faux-naïve but less child-like, featuring many bared teeth and angry expressions; the faces of the daimons look something like the satyr masks of ancient comedy. Every page has at least one illustration and some single illustrations fill two-pages.

In simplifying the narrative to create a short text, choices have inevitably been made about what to include, reduce, or exclude. One interesting omission is the section in which Socrates discusses his military record with the court. Plato's Socrates cites his service in the campaigns at Potidaea, Amphipolis, and Delium (Plato, Apology, 28e), using them as an example of his obedience to law and duty as well as of his lack of fear of death. The omission of this section creates a different impression of Socrates; this is a less active, less physically brave, less civically practical Socrates, whose claim to have been of service to his city becomes more dependent on the value of his philosophy. The author perhaps deemed military service incompatible with his view of the life of a philosopher (despite his own military service), and in omitting it gives us his own version of the philosophical life. Young people and adult non-specialists reading this work are unlikely to notice the omission and as such receive a simplified, arguably sanitised, version of the life of Socrates, or of what 'a philosopher' is and does. In a rare addition to the ancient tradition, this Socrates mockingly imitates one of his accusers in court, with the support of the narrator. The narrator has Meletus call out 'in his falsetto voice', and Socrates is said to reply, 'imitating his accuser's squeaky voice' (p.12-13). This is a curious addition to include. It is clearly intended to disparage Meletus and to make Socrates appear more assertive, yet Socrates is shown to act in a manner that many would find unbecoming in a philosopher, finding humour in a perceived failing of masculinity and attacking another through implied personal criticism rather than reasoned argument. Throughout the work Socrates' behaviour and conversation acts explicitly and implicitly as a model to be followed, but in this exchange the modern representation does not make Socrates a good example. A Socrates who apparently does not do military service but does attack another man for having a high voice is a creation of modern rather than ancient values.

The extensive space given to Socrates' discussion of death and the afterlife encourages the reader to engage well with this aspect of ancient thought and philosophical technique. The illustrations are particularly helpful here. Whilst this is the stage in which they become most surreal, it is also the point in which they are most helpful for breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks and making them more comprehensible by illustration of abstract ideas. The work as a whole creates opportunities for young (and older) readers to explore many challenging subjects, including death and the afterlife, the nature of knowledge, and the disturbing prospect of society's capacity to condemn to death someone who has served that community. Hades is presented as an unusually bright and colourful place, not the quasi-hell that is common in modern representations. The frequent depiction of Socrates amongst his friends and family help the reader to picture the scene of Socrates' imprisonment and to reinforce the idea of the importance of dialogue in this form of philosophy. The illustration of Socrates holding his infant son with his two boys at his knee is a particularly humanising image that may help readers to identify with him. The simple yet creative style of the illustrations invites the reader in and creates a playful, lively rendering of the story. One thing that the reader does not receive, however, is any guidance on how they might find out more about this subject or where the author got their information from. There is no reference to Plato's (or Xenophon's) work on this subject and no information about this being a paraphrased version of ancient material. In this sense the reader may finish this work more informed about ancient philosophy but not more empowered to go further. That said, Les Petits Platons and similar series are symptomatic of a wider desire to give young people a robust introduction to philosophy. While the books are designed to have visual appeal for young people, much of this demand must be driven by adults, presumably those looking to works on established philosophers to develop young people's minds and positively influence their development. Such introductions equip young people to explore life and their own learning with support gained from knowledge of major thinkers and ancient philosophy provides a foundation for this exploration.