Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

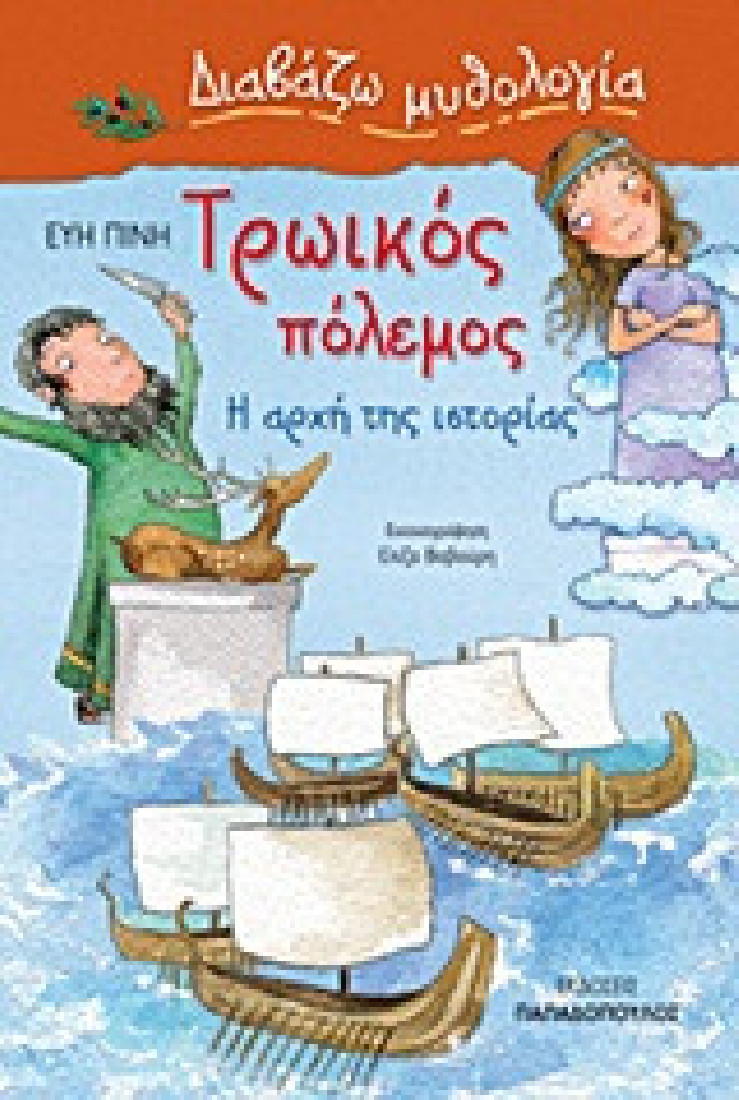

Evi Pini, Τρωικός Πόλεμος. Η αρχή της ιστορίας [Trōikós Pólemos. Ī archī́ tīs istorías], I Read Mythology [Διαβάζω μυθολογία (Diavázo mythología)] (Series). Athens: Papadopoulos Publishing, 2012, 32 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Instructional and educational works

Myths

Target Audience

Children

Cover

Courtesy of the Publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Susan Deacy. University of Roehampton s.deacy@roehampton.ac.uk

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Evi Pini (Author)

Athens-born Evi Pini studied Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Pini has been working for the Greek Ministry of Culture since 1990, specialising in children’s educational programmes.

Sources:

Information about the Author, see here (accessed: June 26, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Elisa Vavouri (Illustrator)

Elisa Vavouri studied at the Bakalo School of Design in Athens. Vavouri, who now lives in Germany, has been working as a professional illustrator of children’s books since 1995.

Source

Profile at the EP Books website (accessed: May 30, 2018).

Bio prepared by Katerina Volioti, University of Roehampton, Katerina.Volioti@roehampton.ac.uk

Summary

Evi Pini explains how the Trojan War started. The text is in the form of a fairy tale, as implied by the standard phrase “once upon a time” (my translation) at the very beginning. The book begins with Eris and ends with Iphigeneia’s last-minute rescue from being sacrificed to Artemis. Neither fighting nor bloodshed is presented. Instead, we have an account of human and divine passions and emotions, as well as a description of logistical preparations for going to war.

Children learn about a minor goddess, Eris, who throws a golden apple. The contest between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite is difficult to resolve, even for Zeus himself. The three goddesses are shown as being angry, and Zeus perplexed. Finally, Zeus asks Paris to choose. Paris picks Aphrodite. The author clearly states that the real incentive for going to war is the Greeks’ desire to loot Troy’s treasures. The (visual) narrative of “1186 ships” gathered at Aulis is realistic. Readers may imagine a military campaign that happened in history and not a mythological time.

Unintentionally, Agamemnon makes Artemis angry by killing her favourite stag, and the goddess demands that Agamemnon sacrifice Iphigeneia, his daughter, in recompense. Agamemnon shares his devastation with other kings in his tent, which communicates messages about male solidarity and ways to cope with grief. Odysseus comes up with a lie so that Iphigeneia and her mother think they are going to a wedding and not a sacrifice. Achilles promises to defend Iphigeneia, but she is prepared to die. Yet, at the moment of the sacrifice, a cloud covers the altar, Iphigeneia disappears, and a deer is sacrificed instead. Divine intervention here brings hope rather than misery, and the book closes on a positive tone. We are told that Iphigeneia went far away, and there is another story to tell at another time.

Analysis

This short book is exceptionally rich. Children learn the names of numerous gods, heroes, and places (see, in particular, pages 20-21 with a catalogue of kings and places). The topics covered are wide-ranging and include war, love, jealousy, revenge, and desperation. Children form an impression of qualities valued in modern times, such as teamwork, ingenuity, solidarity, and stereotyped notions of gender.

The language is simple, and the many colloquialisms that are popular in modern usage add vitality to how the story unfolds. Although the book is designed to be read by children independently, the story can also be read by teachers or museum education officers.

The illustrations by Elisa Vavouri appear to take cues from Bronze-Age frescoes and archaeological finds, as appropriate for the timeframe of the Trojan War. For example, the white helmets worn by Agamemnon and Menelaus recall a well-known boar’s tusk helmet excavated at Mycenae and is kept today in the National Archaeological Museum, in Athens. Text and image work well in this booklet, offering a tale from the deep past that has left historical and archaeological traces for us today.

The coupling of mythological and historical events gives credence to the narrative. On the opening page, children read that the greatest heroes of ancient Greece took part in this war, which has connotations for historicity and identity-building. The story is about human and divine affairs and the differences and similarities between mortals and gods.

On the whole, mortals are rather weak. Paris appears to be fragile, and Aphrodite guides him all the time on his trip to Sparta and the abduction of Helen. Agamemnon is at a loss, and he needs his brother and other warrior kings to launch his campaign against the Trojans. There is an emphasis on the salience of teamwork and the large numbers of kings and ships, as these could counterbalance mortals’ weaknesses. There is nothing about male decisiveness in the story. Instead, mortals are at the mercy of the gods’ desires. Agamemnon has to take Achilles with him because a seer said so.

Odysseus, being inventive, manages to reveal who Achilles is from amongst a group of females in Lykomedes’ palace on the island of Skyros. There are gender issues here, reflecting diachronic stereotypes in male and female behaviour and appearance, and children may identify with these stereotypes. Achilles is interested in weapons and not in the fine cloth for garments that Odysseus offers him. The illustrator shows Achilles as a blond, and with good reason as this is how Homer describes Achilles, but also with a broad square face with prominent cheekbones, suggestive of Achilles hyper-masculine character, as befitting a brave warrior.

Aphrodite’s beauty is probably indicated by her long blond hair, tied up with a blue ribbon matching the colour of her long dress. Helen, by contrast, has black hair and more elaborate and colourful clothes on, recalling a Bronze-Age lady. Thus the illustrator offers a fuller view of what female beauty entailed.

Further Reading

Information about the book at epbooks.gr, published in Greek 10 October 2011 (accessed: August 3, 2018).

Addenda

Published in Greek. From a series entitled “Διαβάζω Μυθολογία” [I read Mythology].