Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

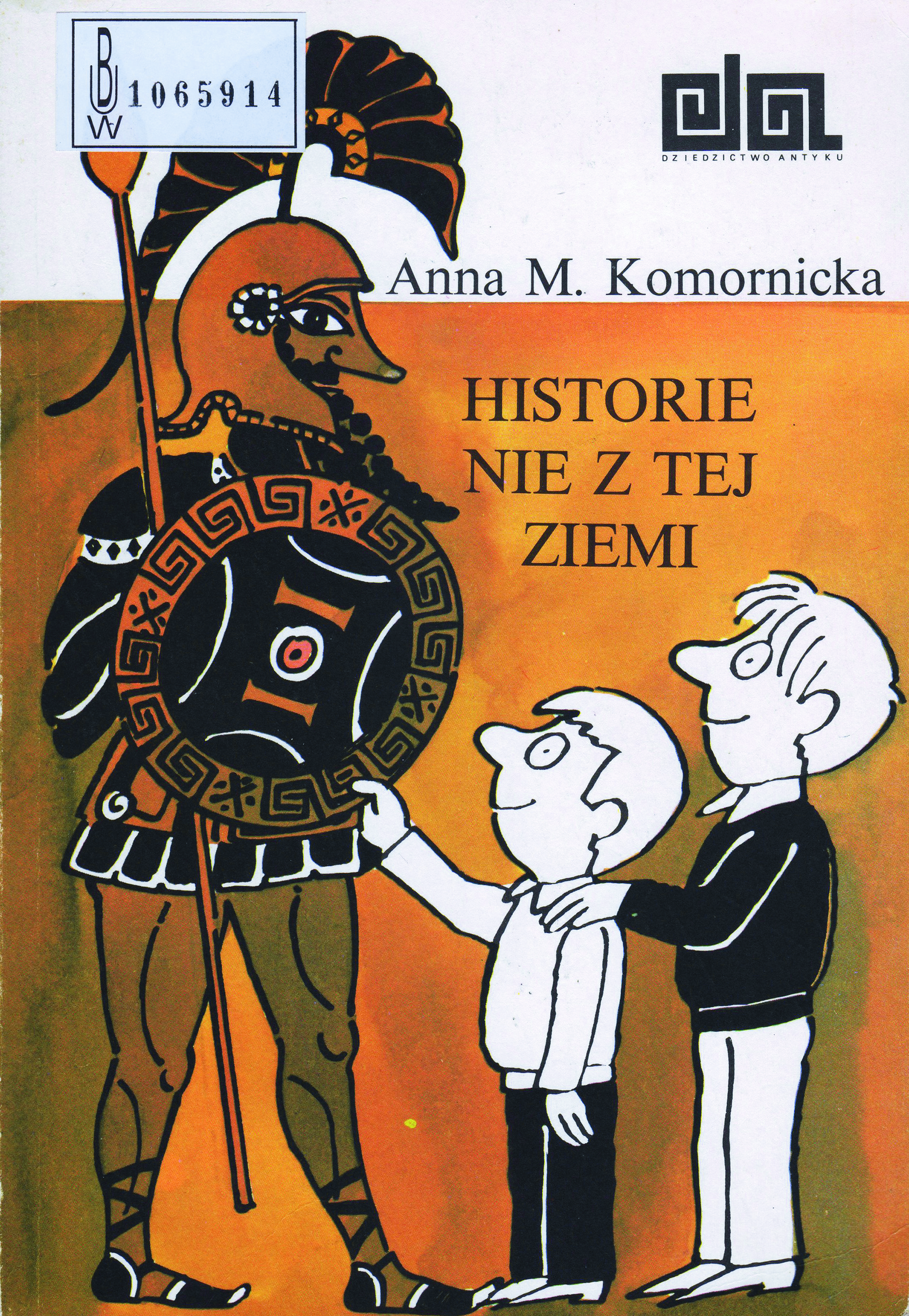

Anna M. Komornicka, Historie nie z tej ziemi, "Dziedzictwo antyku". Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Radia i Telewizji, 1987, 165 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Short stories

Target Audience

Crossover (Children, teenagers)

Cover

Cover design and illustrations by Jerzy Flisak (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Radia i Telewizji, 1987), courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Olga Grabarek, Univeristy of Warsaw, olga.grabarek@student.uw.edu.pl

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

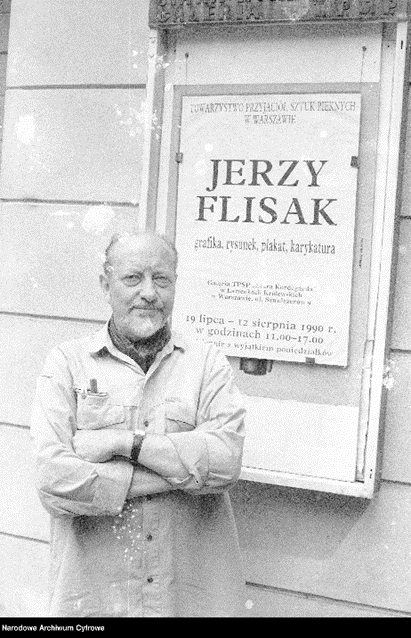

Jerzy Flisak

, 1930 - 2008

(Illustrator)

Jerzy Flisak was a Polish graphic artist, illustrator, and scenographer, well-known for his drawings and posters. He graduated from the Warsaw University of Technology [Politechnika Warszawska] with a diploma in architecture. His drawings were published in various weeklies, including Szpilki [Scores], where he was the graphic editor, Polityka [Politics], Świat [The World], Przegląd Kulturalny [The Cultural Review], and periodicals aimed at children, such as Świerszczyk [The Little Cricket] and Płomyczek [The Little Flame]. For Świerszczyk he created a popular comic column Co robi nasz Bobik [What’s Up with Our Bobik] about an amusing dog that children liked the most (see here and here, accessed: April 7, 2022). Jerzy Flisak was also the author of illustrations for many children’s books creating his own style. He worked as well for Short Film Forms Studio Se-Ma-For in Łódź and Animated Cartoons Studio SFR in Bielsko-Biała.

Source:

Culture.pl (accessed: April 7, 2022).

Poster.pl (accessed: April 7, 2022).

Bio prepared by Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Photograph courtesy of the Author.

Anna M. Komornicka

, 1920 - 2018

(Author)

Classical philologist, specialized in Greek comedy and archaic lyric poetry; her research covered also texts of the Greek Fathers, reception of the Bible, genesis and evolution of concepts in ancient literature; translator of Greek and Roman, as well as contemporary literature into Polish; Editor-in-Chief of the classical journal “Meander”; author of books and radio-plays inspired by Antiquity for children and adolescents. Honorary Member of the Scientific Committee on Ancient Culture of the Polish Academy of Sciences (KNoKA PAN).

Sources:

Jadwiga Czerwińska, “Profesor Anna Maria Komornicka, nasz mistrz”, Meander 63 (2008): 4–14 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Anna M. Komornicka, “Anna M. Komornicka: Listy do Meandra”, Meander 74 (2019): 179–201 (accessed: March 29, 2021).

Jan Komornicki, “Pożegnanie Cioci Anny z Wolańskich Komornickiej (27 września 1920 – 17 grudnia 2018)”, Meander 74 (2019): 3–8 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Bio prepared by Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Sequels, Prequels and Spin-offs

Anna M. Komornicka, Nić Ariadny, czyli po nitce do kłębka, Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Radia i Telewizji, 1989.

Anna M. Komornicka, Alfa i Omega, czyli starożytność w miniaturze, Warszawa: Oficyna Wydawnicza Ostoja, 1995.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue (accessed: June 11, 2021), Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp., section by Elżbieta Olechowska and Olga Grabarek, pp. 128–131.

This is the first volume in the series The Legacy of Antiquity. The heroes of the book are siblings: Krzyś, Stefanek and Elżbietka. They live with their parents and grandmother Bunia. The Mother introduces the kids to the world of myths, telling them about mythological heroes, such as Achilles and Icarus. Children fascinated by these stories give free rein to their fertile imagination and become heroes of seemingly ordinary events during which they meet characters far from the ordinary. They wonder often, if what happened to them, happened really, or if it was just a dream. Each adventure is a great lesson for them, from which they draw conclusions.

Analysis

To introduce children to the world of Greek myths, the author chooses the strategy of using children protagonists. Instead of a boring lecture, she constructs a coherent narration full of interesting situations and adventures. The child reader learns about antiquity along with the protagonists. Mythical content is displayed in four ways: through storytelling evenings once or twice a week promised by the mother, as part of everyday life (ancient echoes in vocabulary, expressions, references in culture), through their own research undertaken from curiosity, and finally – through fantastical meetings with particular Greek gods and heroes in contemporary reality. In each chapter, another situation serves as a pretext to introduce mythological characters or stories easily. The author uses many potentially didactic elements of classical antiquity and allows the protagonists to draw their conclusions and arrive at a hidden moral lesson. The book has undeniable values for both education and upbringing.

The book introduces seven mythical plots interwoven into the children’s adventures. Asclepius and Hygeia, Hypnos and Parcae, Achilles and Odysseus, Icarus, Hermes and Zeus, Phaethon, Demeter and Kore are the main Greek characters met by the children or presented in specific chapters. The myth of Demeter and Kore provides a frame to the entire composition – in the first chapter, the children are told that the ancients explained the origin of the seasons through a story about the gods. In the last chapter, the protagonists themselves, along with their friends, stage the myth of Demeter’s grief for a private audience, as if they were performing in an actual theater.

The first mythological figure presented to the reader is Asclepius. He appears as an older doctor visiting the 11-year-old Krzyś, who seems to be unwell, but is only faking an illness to be able to remain at home and read the Mythology by Jan Parandowski, his favorite birthday present. The doctor, who uses a snake as his stethoscope, is aware of the ruse, especially about Krzyś’s unfinished homework, and writes his diagnosis in Latin as simulatio vitiosa. During the doctor’s exam, the boy learns a lot about Asclepius, his parents and descendants, non-human custodians, wide-ranging education and working methods. Before the mythical doctor leaves, he writes a prescription. Krzyś admits to his worried mother that he was faking, and in return, she reveals that the doctor prescribed telling the truth to the parents and always completing homework.

In the following chapter, the situation becomes serious. The boys are terrified by their mother’s illness. They meet a mysterious doctor’s assistant who is Hypnos himself. He leads them to an attic in the neighborhood where three Parcae decide people’s fates. The women are presented as ugly old workaholics relentlessly performing their duties. Hypnos says that they are merciless, can never be appeased and that they were tricked only once – by Apollo for Admetus. He helps the boys save their mom’s life. Hypnos makes the women take a nap and the boys, despite their fear, manage to knot a new thread to the skein, giving their mother additional strength to defeat her illness.

The next chapter is set during the holidays spent by the boys in a forester’s lodge. On a small lakeshore, where they once spotted Thetis bathing baby Achilles, they meet two ancient armed warriors: Odysseus and Diomedes. They accompany them to Skyros to help them find a lost teenager, Achilles. Onboard an ancient trireme, they are shocked by the appalling working conditions of rowers. At Lycomedes’ hospitable palace, they realize that Odysseus’ intentions are not clear – he does not want to find Achilles for his mother’s sake but for his own purpose. The author vividly describes Lycomedes’ palace, the community, organization, fashion and customs, including the separation of women – they live in a designated part of the buildings and do not take part in social life. The boys discover that the red-head Pyrrha is, in fact, a boy hidden by his mother, and they try to help him remain disguised rather than reveal his secret, to please Odysseus. The sneaky Odysseus arranges for the sounding of a fake alert at the farewell feast, and Achilles’ true identity is revealed. Bored of female company, the boy puts on his armour and sets off for the Troy campaign. Fortunately, his new friends are not aware that he would perish there, wounded in the heel by a lethal arrow.

The myth of Icarus is presented at the occasion when the children move and change school. They are accepted and liked by their new schoolmates, including Icarus, a new boy who joins Krzyś’s class. He is brilliant, intelligent, kind, humble and helpful but seems to be hiding a secret. When they read together Metamorphoses by Ovid, everyone wants Icarus to loudly read the story about Daedalus and Icarus because of his name; the boy, however, almost cries while reading. Sometime later, it turns out that he works in secret in a hangar. In the beginning, the boys think he is a spy, but Elżbietka decides to give him a chance and tell them his story. So they learn the myth of Daedalus and Icarus, told from an inside perspective as a story of a father and son who escape from the island of Crete. Children ask him to say some phrases in ancient Greek to test him. He quotes verses from Hesiod’s Works and Days and Aristophanes’ Frogs. What is important, the contemporary plot maintains features of the ancient story, like Icarus, who after a long torment in the underworld, still keeps his dream about flying. The children help him finish the plane he has been constructing, and finally, he can fly away towards the sun to fulfill his dream.

The next chapter's protagonist is Elżbietka, who meets a stranger who turns out to be Hermes. He is recognizable because he is shown according to ancient depictions: he can talk with animals, wears a petasos hat, cloak, winged shoes, a caduceus and a big pouch full of interesting objects such as Hesperides’ apples, Orpheus’ pipe, Zeus’ thunderbolt and the kallisteion, the golden apple of Eris. He exchanges the items with the children for a contemporary cap and jacket and then leaves. The magical objects make the children’s evening amusing and extraordinary: Stefan charms nature with the music he makes with his new instrument, Elżbietka is voted the most beautiful and becomes the belle of the ball, and Krzyś uses the thunderbolt to cause a storm preventing them from going home. The magical items must be returned because they were stolen. Finally, Zeus recovers the objects, however, the story ends on a humorous note: an old countrywoman accidentally eats the apple and transforms into such a beautiful young girl that Zeus takes her to Olympus with him.

The next myth is the story of Phaethon’s fall. The children have a biking accident in the forest, and there they find Phaethon, battered after the chariot crash. He tells them about hearing unpleasant gossip of being adopted, which caused him to ask Helios to grant his outrageous wish – to ride the sun chariot. The father, worried about the risks, asks him instead for another wish but when the son refuses, Helios must keep his promise. Fortunately, after breaking the chariot, Phaethon falls to the ground alive, though with bruises. The children are blinded by the sun rays, when the father taken his son away. In his place, they find a page from Ovid’s Metamorphoses describing the Sun’s palace exactly as Phaethon described it.

The last chapter sums up all that the children have learnt about mythology and the ancient world. For their parents’ anniversary, they prepare an elaborate and detailed spectacle presenting the myth of Demeter and Kore, engaging their friends and using all the knowledge they acquired.

Further Reading

Czerwińska, Jadwiga, “Profesor Anna Maria Komornicka, nasz mistrz”, Meander 63 (2008): 4–14 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Czerwińska, Jadwiga, “Z Grzymałowa w świat antyku”, Cracovia Leopolis 43 (2005): 2–5, 51 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Komornicka, Anna M., “Anna M. Komornicka: Listy do Meandra”, Meander 74 (2019): 179–201 (accessed: March 29, 2021).

Komornicki, Jan, “Pożegnanie Cioci Anny z Wolańskich Komornickiej (27 września 1920 – 17 grudnia 2018)”, Meander 74 (2019): 3–8 (accessed: June 11, 2021).

Marciniak, Katarzyna, “(De)constructing Arcadia: Polish Struggles with History and Differing Colours of Childhood in the Mirror of Classical Mythology”, in Lisa Maurice, ed., The Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome in Children’s Literature: Heroes and Eagles, “Metaforms: Studies in the Reception of Classical Antiquity”, Leiden–Boston: Brill, 2015, 56–82.