Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Elżbieta Olczak i Elżbieta Lubomirska, Mity greckie na wesoło. Warszawa: Muza, 2005, 64 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Myths

Target Audience

Children

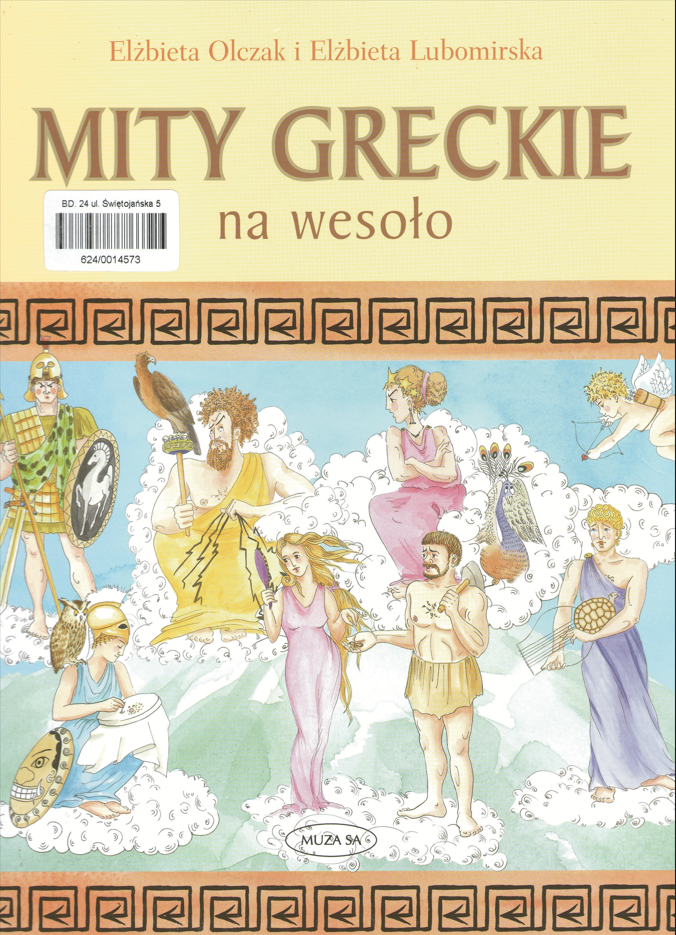

Cover

Courtesy of Elżbieta Lubomirska.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Weronika Głowacka, University of Warsaw, weraglowacka@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph of the Author with her dog Niunia, courtesy of the Author.

Elżbieta Lubomirska (Illustrator)

MA in Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw; MA in Education at the University of Warsaw. She also completed a postgraduate Study of Psychotherapy at the Institute for Process Oriented Psychology in Warsaw. She freelanced for TVP2 (Public Television) and Studio Miniatur Filmowych (a production company specialising in short movies) in Warsaw, designing and implementing animation of fairytales for children. Since 1999, she has collaborated with a number of publishers: Nowa Era, Pracownia Pedagogiczna, DEMART, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, MAC Edukacja, Wydawnictwo Szkolne PWN, Wydawnictwo Edukacyjne Kraków, Grupa Edukacyjna, Bellona.

Bio kindly provided by the Author.

Photograph courtesy of the Author.

Elżbieta Olczak

, b. 1967

(Author)

Elżbieta Olczak graduated from the Faculty of the Humanities of the Catholic University of Lublin (KUL) in History. After graduation, she studied French in Paris for a year and obtained a diploma there. She taught history for the next eight years at general education high schools in Gdynia. During the following decade, she worked in a publishing house in Warsaw, designing and editing educational texts for teaching history: textbooks, exercise books, historical atlases, acetates, and teaching aids. She also edited popular publications in the area of art history, often at her initiative and according to her design.

During this time, she wrote and published educational materials: Historia. Zeszyt do ćwiczeń na mapach konturowych dla liceum [History. Book of Exercises on Contour Maps for High Schools], 2001; Historia. Zeszyt ćwiczeń dla 1 klasy gimnazjum [History. Book of Exercises for Grade I of Gymnasium], 2002; Historia. Szkoła podstawowa. Zestaw foliogramów [History. Elementary School. Set of Acetates], 2006; she also co-authored Spotkania z historią. Atlas z komentarzami źródłowymi dla gimnazjum [Encounters with History. An Atlas with Source Commentaries for High Schools], 2007. With Elżbieta Lubomirska she wrote Mity greckie na wesoło [Greek Myths for Fun], 2005; with Małgorzata Balsewicz Historia Polski – 100 wydarzeń [History of Poland — 100 Events], 2010. She is currently working for the WW2 Museum in Gdańsk, in the research section, organizing the permanent exhibition of the new Museum, including a show space designed for children and young people. She also supervises preparation of scholarly books published by the Museum.

Bio kindly provided by the Author.

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

The book is a collaborative work: Elżbieta Olczak wrote the text, and Elżbieta Lubomirska prepared the illustrations and the book’s design. The most important Greek gods and the myths about them are presented pleasantly and amusingly. The gods look and behave like average humans, with all their virtues and vices. Some topics, like love, betrayals and romances of the gods, usually difficult to understand for very young children, are presented in an accessible and amusing way. Colourful illustrations show the main features of the gods and their stories; the book also contains descriptions of individual gods. It begins with an interpretation of myths about Zeus, followed by myths about Hera, Athena, Poseidon, etc. The language is simple and adapted for very young readers. The maps of Ancient Greece help to situate locations referred to in the myths, making mythology easier to understand.

Analysis

In the introduction, the author makes the reader aware that knowing Greek myths is necessary for people who do not want to appear ignorant. The book serves this need by presenting the main Greek gods and some myths they are involved with. The Olympians are seen here as a family and presented on separate pages.

The text is simple and easy to read, resulting in stereotyped presentations of the gods and a language based on contemporary vocabulary traditionally not associated with the Greek gods (e. g., Zeus is called "olimpijska szycha", a “big shot”, Dionysus "bóg napoju rozweselającego", “the god of joyful drinking”). The gods’ characters are very simply labelled; they are one-dimensional, and no analysis is provided, probably to make it easier to remember their function, attributes and related myths. However, some labels can be regarded as potentially inappropriate if the reading is left without comment from an adult. A good example is the myth of Apollo and Daphne, where Apollo is called a “god whose love was unrequited” while the perspective of his victim, Daphne – who escaped rape – is not developed. An unopposed point of view is used while depicting Zeus and Hera. The chapter “Zeus the Thunderer, the Olympian Fat Cat” begins with Zeus’ attributes and the people and causes he supports. The general impression is that he favours troublemakers or hooligans. A mention of his love affairs with Leda, Europa and Danae leaves the reader with an image that mighty fat cats were allowed to do to women what they wanted, whether women gave their consent or not. The chapter on Hera is entitled “A Proud Protectress of Women”, but the goddess is presented as haughty and vindictive, and there is a separate story: “How Hera persecuted Io”. The plot again follows a man’s point of view, ignoring the perspective of a repeatedly cheated-on wife or Io, seduced by the husband and punished by the wife.

Hades is described as gloomy, unapproachable, and grim. This impression is reinforced by the illustration showing him wearing black garments and holding a devilish pitchfork, surrounded by nightmares. The black background is designed to heighten the terror. The child reader may be concerned to learn that Hades’ servants, the Erinyes, also haunted children who were disobedient (p. 44).

The myth of Aphrodite is told from a different perspective. She is presented as a person constant in her feelings: she rejected all suitors because of her love for Adonis. Because of Persephone’s envy, she lost her beloved and mourned him desperately – that was why Zeus allegedly divided the year into two parts to comfort her in her bereavement – Adonis was allowed to return every six months to join her. In the myth of Hephaestus, the marriage with Aphrodite is perceived by the bridegroom not as a reward but as a mockery of his unattractive appearance. On the other hand, as Aphrodite’s love affair with Ares is not developed, also Ares is presented as a dismal, aggressive killer, a bully, quarrelsome and without any redeeming features. Only Hades likes him for sending so many warriors to their death.

Some characters seem more complex and even ambiguous, like Artemis, who, on the one hand, is shown as the guardian of balance, divine norms of the hunt, and protectress of game and wildlife from unnecessary cruelty, highlighting the importance of sustainable forest management. Still, on the other, she is unusually cruel to those who “sinned” without the intention of offence, like Actaeon and Callisto.

In conclusion, the book provides a basic introduction to Greek mythology but does not confront it with today’s interpretations. The title, Greek Myths for Fun, alludes to quite a few changes in the myths meant to lighten up the stories, which are often not funny.

Further Reading

[The Illustrator’s Website], http://elkacprzak.eu/ (accessed April 05, 2013).