Title of the work

Studio / Production Company

Country of the First Edition

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Олимпионики [Olimpioniki (Olimpioniki)]. Written and directed by Fyodor Khitruk. Composer Sándor Kallós. Moscow: Soyuzmultfilm, 1982.

Running time

Genre

Animated films

Hand-drawn animation (traditional animation)*

Instructional and educational works

Live-action animation films

Target Audience

Children (6+, crossover)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Dorota Mackenzie, University of Warsaw, dorota.mackenzie@gmail.com

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

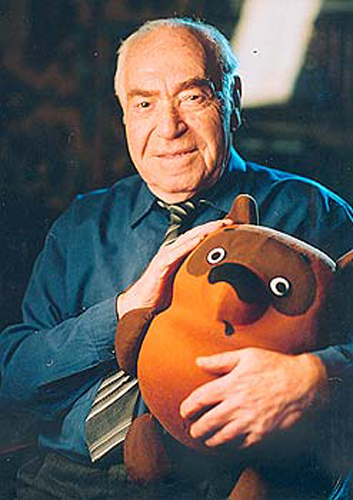

Zinovy Gerdt

, 1916 - 1996

(Actor)

Zinovy Gerdt (Зиновий Гердт, born as Zalman Chrapinowicz) was a prolific Russian actor, People’s Artist of the USSR. He started his theatrical career at the Workers’ Youth Theatre (1932), and worked a lot in the Sergei Obraztsov State Academic Central Puppet Theatre (1945–1982). He also began work in the cinema as a dubbing actor, having many different roles afterwards.

Bio prepared by Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Sándor Kallós

, b. 1935

(Composer)

Sándor Kallós (Шандор Каллош) is a Russian composer (of Hungarian descent). He wrote music for animation, cinema and theatre. As a lutenist he played in the Ensemble Madrigal (Moscow) reviving early music (from 1971). He was also a promotor of electronic music in the USSR.

Bio prepared by Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Courtesy of the project www.kino-teatr.ru (accessed: June 28, 2018).

Fyodor Khitruk

, 1917 - 2012

(Animator, Director)

Fyodor Khitruk was an outstanding Russian and Soviet animator, animation director, screen writer, pedagogue, and translator. He made movies for children as well as for adults. His first movie История одного преступления (A Story of One Crime, 1962) is perceived as the beginning of the new wave in Soviet animation. His most famous movies for children are his Winnie-the-Pooh series. He is also famous for Остров (An Island, 1973), Фильм, фильм, фильм (Film, Film, Film, 1968), Человек в рамке (A Man in a Frame, 1966). He taught for many years on courses for directors and has created a school of Russian animation.

Fyodor Khitruk was awarded by many orders and won many competitions.

Bio prepared by Hanna Paulouskaya, University of Warsaw, hannapa@al.uw.edu.pl

Adaptations

The movie was made after the creation of a full-length documentary film О спорт, ты — мир! [O Sport, You Are Peace!] by Yuri Ozerov in 1981. Fyodor Khitruk participated in the preparation of the animated part of this live-action/animation film. The documentary concentrates on the Moscow Olympics using ancient motifs in a small measure compared to the animation under discussion.

О спорт, ты — мир! [Oh Sport, You Are Peace! (O sport, ty — mir!)]. Directed by Yuri Ozerov. Moscow: Mosfilm, 1981. 149 min.

Summary

This is an educational movie describing the history of the Olympic Games in the form of short funny stories. It was filmed during the 1980 Olympics held in the USSR.

The movie is animated, however its last part includes found footage – documentary photo and video materials from modern Olympic Games, finishing with the Moscow Olympics. The animated material is based on ancient vase painting, sculptures, and architecture that is included extensively in the film.

It talks about the origins of the Olympic Games and retells some funny anecdotes from their history. The movie consists of the following parts:

1) Origins of the Olympics – 1.

The opening retells the story of Zeus winning in the war with the Titans. In the background we see pictures from the Pergamon temple’s bas-relief illustrating the Titanomachy. The fragment is filmed and animated by Yuri Norstein.*

The movie then tells a legend about Zeus who wishing to celebrate his victory, established an athletic competition. Apollo defeated Ares and became an Olympic champion. We see white models of famous statues of Olympic gods with Zeus’ sculpture in the centre. They form a triangular shape recalling a temple entrance pediment. A statue of Apollo fights with a statue of Ares looking like toy soldiers.

Thus both the motif of ancient mythology and Greek art are promoted in the film. It is emphasized that the story is only a legend, so the movie does not promote religion in any form, as required by the anti-religious culture of the Soviet Union.

2) Origins of the Olympics – 2. Story of Iphitos from Elis.

In this part, we see how the city-state of Elis was close to ruin due to constant wars in Greece. Iphitos, King of Elis, went to the Delphic oracle asking how to stop the war. The oracle told him to call all the Greeks to Olympia and to establish sporting competitions. For the duration of the games the war was to be stopped.

The animation does not mention that this is one of many theories about the origins or revival of the Olympics.** The movie presents only this version, choosing the one about the peacemaking power of the Olympic games, highly topical in 1980.

3) The first Olympics in 776 BC. The Olympic oath. Olympic calm vs Olympic excitement.

The narration of the Olympics starts in the form of a live TV report, using contemporary terminology and familiar intonations.

The reporter talks about Coroebus of Elis who won the first recorded Olympic Games in 776 BC (Strabo, Geography 8.3.134). According to the movie he was a waiter and won the stadion thanks to his profession. He had to run every day so often and so quickly between the tables that he was well trained for the victory in the Olympics. There is a late testimony of Athenaeus who calls Coroebus a cook (9.382B), however here the authors went farther adding some logical explanation to his profession.

The prize for the winner was an olive branch. The movie also mentions that the Olympics were the basis for the Greek calendar.

4) Explains that Gymnasium schools were formerly gymnastic halls, and children were taught sports and only afterwards other subjects.

5) Explores the 14th Olympics (724 BC).*** Tells the legend of Orsippus from Megara.

Orsippus was a young athlete who participated in the games for the first time.

First, he started his run before time and was punished immediately — he was whipped publicly. He then started his race late, but still he won the stadion. However during the footrace he lost his loincloth and ran naked. The ancients say that he introduced athletic nudity.

The animation presents the origins of nudity in the Olympics as a funny accident in the style of silent-movies’ misadventures. It contradicts the opinion of Pausanias who thought that Orsippus lost the girdle intentionally (Pausanias, Description of Greece 1.44.1).****

Orsippus was memorialized in a sculpture, which was brought to Megara through a break in the city wall. Afterwards the wall was rebuilt, so the victory that had entered the city could never leave again.

6) A woman in the stadium.

The narrative explains that only men could participate and watch the games. It was a bad omen to have a woman in the stadium, and punishable by death — by being hurled from a mountain. (It was Mount Typaeum according to Paus. 5.6.7.)

The story of Pherenike is told. She, being a widow, trained her son Peisidoros for the boxing competition herself. She came to the stadium dressed in male clothes, but when her son won, she could not control her emotions and revealed herself. She was not punished, as she was the trainer of the victor, the animation says. However Pausanias says that “they let her go unpunished out of respect for her father, her brothers and her son, all of whom had been victorious at Olympia. But a law was passed that in the future trainers should strip before entering the arena.” (Paus., 5.6.8)

7) Shows the origins of discus throwing. Advances a theory that discuses were used to deliver messages to besieged cities.

8) Considers the logistics of the long jump. How could the ancients jump such long distances? Maybe these were multiple jumps. For example, Phayllos of Kroton jumped 55 feet (16,3 m) and finished outside the pit. An ancient author says that Phayllos broke his left leg as a result (The Suda). Phayllos is often mentioned in ancient anecdotes, and “jumping outside the pit” became a proverb by itself.*****

9) About the wrestler, Milo of Kroton. In childhood he was a shepherd and carried a sick calf. “With the calf growing, also Milo grew in strength.”******

Milo won the Olympics six times — more than anyone till today.

In the movie he carries his own statues to place on pedestals.

He was also a philosopher, a student of Pythagoras. The movie here follows ancient tradition, however it is more plausible that Pythagoras happened to be the name of his sports trainer.

The film also mentions that many ancient intellectuals took part in the Olympics — Aristotle, Plato, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Socrates etc.

The ideal man represented a harmonious union of intellect and physical fitness.

10) The Olympics are also presented as not devoid of cruelty and inciting the public to gambling. We see strong emotions in the audience.

The history of Nero participating in the games is told. He takes part in the chariot racing, starts the race earlier than others, falls from the chariot a few times, but is placed on the chariot by his servants, and wins the competition while being praised by the public (Suetonius, Nero 22-25).

11) Gladiator games are presented as a part of the Olympics.******* The problem of cruelty and death is shown here.

12) Roman legions were the reason for the end of the Olympics. This episode does not provide a clear explanation — we see Roman legions marching and there is a sentence indicating that the Olympics ended with the arrival of the legions.

13) The modern Olympics. The history of the revival of the Olympics in the 19th and 20th century is presented with photographs and documentary videos of some of the sportsmen from different periods.

*Georgy Borodin tells that Norstein was the author of the fragment with the Pergamon altar. Borodin, Georgiĭ [Бородин, Георгий], “Олимпиада как мультфильм” [Olympics as an Animation ("Olimpiada kak multfilm")], Сеанс [Seans (Seans)]: 55-57, online resource (accessed February 01, 2018).

**Kyle, Donald G., Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2014 (ed. pr. 2007), 98.

*** According to contemporary scholarship, it was during the 15th Olympics, in 720 BC.

**** Kyle, Sport and Spectacle…, 84.

***** More about ancient references of Phayllos and their credibility see: Harris, H. A., “An Olympic Epigram: The Athletic Feats of Phaÿllos”, Greece & Rome 7.1 (March, 1960): 3-8; Miller, Stephen G., Arete. Greek Sports from Ancient Sources, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004, 46-48.

****** In the documentary carrying of the bull by Milo is explained as carrying a 4-year old bull to be eaten by the wrestler himself, according to the ancient anecdote. The animated version may be more suitable for children.

******* Kyle, Sport and Spectacle…, 257-267.

Analysis

The Moscow Olympics became the reason for the creation of many animations about the games. Only a few of them dealt also with the ancient games.* Fyodor Khitruk’s movie is dedicated to a description of the ancient history of the games; only in small measure does it bring up the revival of the games in the modern times.

The main theme of the film is the role of the Olympics as a guarantee of peace, which is common also for other animations about antiquity and the Olympics taking place in the USSR in that time. The topic was especially relevant in 1980, when several countries declined to participate in the games due to the Afghanistan campaign of the USSR. However none of the movies mentions the details of the political situation — they appeal for peace on an abstract level. Using myths in this context gave an even greater opportunity not to mention the details and to speak metaphorically. In the case of Khitruk’s movie peace is only one of many other topics presented.

An important motive of the movie is physical culture and beauty of physical body. It is emphasized through canonical Greek representations of human bodies in the drawings of the sportsmen. Physical culture was an important part of the Soviet culture from the 1920s, when physicality gained its importance in the country and in the whole of Europe. At that time also the Olympics and Greek culture became the foundation for this movement. With developing of medicine and changes in educational system, physical training entered into the European culture and became its integral part. It is especially emphasized in art representations of ideal human bodies produced in that period across Europe. The importance of sport is underlined in the movie, also in the listing of famous philosophers who, according to the authors, were deeply engaged in sports. Sport obtains a philosophical meaning in this context. The movie pays special attention to discuss different sports that were part of ancient Olympics and to tell their history. The problem of nudity and its omnipresence in classical culture is also mentioned, however this aspect has only anecdotal interpretation.

Women and limitations of their rights is another topic of the movie. It is especially obvious in the story of Pherenike. Contemporary society is presented as more advanced and protective of female rights. The possibility for women to take an active part in sports competitions takes on an additional importance due to this.

The narration consists of short stories, intended to make watching easier even for small children. It also resembles ancient anecdotes describing famous figures of the winners of the games. The versions of the stories chosen for the movie are not always close to the sources, as the emphasis is placed on entertainment. Due to this, the movie is very child-friendly. Classical history told in the form of short stories for children refers to a context of classical gymnasia, where children were taught languages reading short texts adapted to their level of command of Latin and Greek and ability to understand complex moral problems. Although classical education was not continued in the Soviet Union after the revolution, the type of narration used in the movie refers to traditions of classical education, which was the basis for the school system in Russia and the neighbouring territories before 1917.

* Borodin, Georgy, “Олимпиада как мультфильм” [Olympics as an Animation]. Сеанс [Seans]: 55-57, online resource (accessed on February 01, 2018) .

Further Reading

Borodin, Georgiĭ [Бородин, Георгий], “Олимпиада как мультфильм” [Olympics as an Animation ("Olimpiada kak multfilm")], Сеанс [Seans (Seans)]: 55-57, online resource (accessed February 01, 2018).

Harris, Harold Arthur, “An Olympic Epigram: The Athletic Feats of Phaÿllos”, Greece & Rome 7.1 (March, 1960): 3-8.

Kyle, Donald G., Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2014 (ed. pr. 2007).

Miller, Stephen G., Arete. Greek Sports from Ancient Sources, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004 (ed. pr. 1979).

Petermandl, Werner, “Growing Up with Greek Sport. Education and Athletics”, in Paul Christesen and Donald G. Kyle, eds., A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity, Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2014, 236-245.

Addenda

The Remaining Production Credits

Art director – R. Frichinskaia

Animators – V. Kolesnikova, Yuri Norstein, T. Pomerantseva and others

Sound director – Boris Filchikov

Camera man – Kabul Rasulov

Composer – Sandor Kalloś

Consultant – V. Shteinbakh

Production designers – Liudmila Koshkina, Vladimir Zuikov

Main actors:

Zinovy Gerdt – narrator

Information about the film in movie databases:

animator.ru (accessed: January 31, 2022).