Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Michael Ende, Die Unendliche Geschichte. Stuttgart: Thienemann Verlag, 1979, 432 pp.

ISBN

Awards

1979 – Book of the Month;

1979 – Buxtehuder Bulle;

1980 – Preis der Leseratten des ZDF;

1980 – Wilhelm-Hauff-Preis zur Förderung von Kinder- und Jugendliteratur;

1980 – German Youth Book Prize, nominated;

1981 –European Youth Book Prize;

1982 – Japanese Book Prize for the best translation of contemporary literature;

1983 – Silberner Griffel of Rotterdam;

1983 – Children’s Book of the Year, Spanish Ministry of Culture;

1988 – IBBY Honours List for the best translation into Polish;

1989 – Goldene Schallplatte.

Genre

Fantasy fiction

Novels

Target Audience

Crossover (children, teenagers and adults)

Cover

We are still trying to obtain permission for posting the original cover.

Author of the Entry:

Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Elizabeth Hale, University of New England, ehale@une.edu.au

Lisa Maurice, Bar-Ilan University, lisa.maurice@biu.ac.il

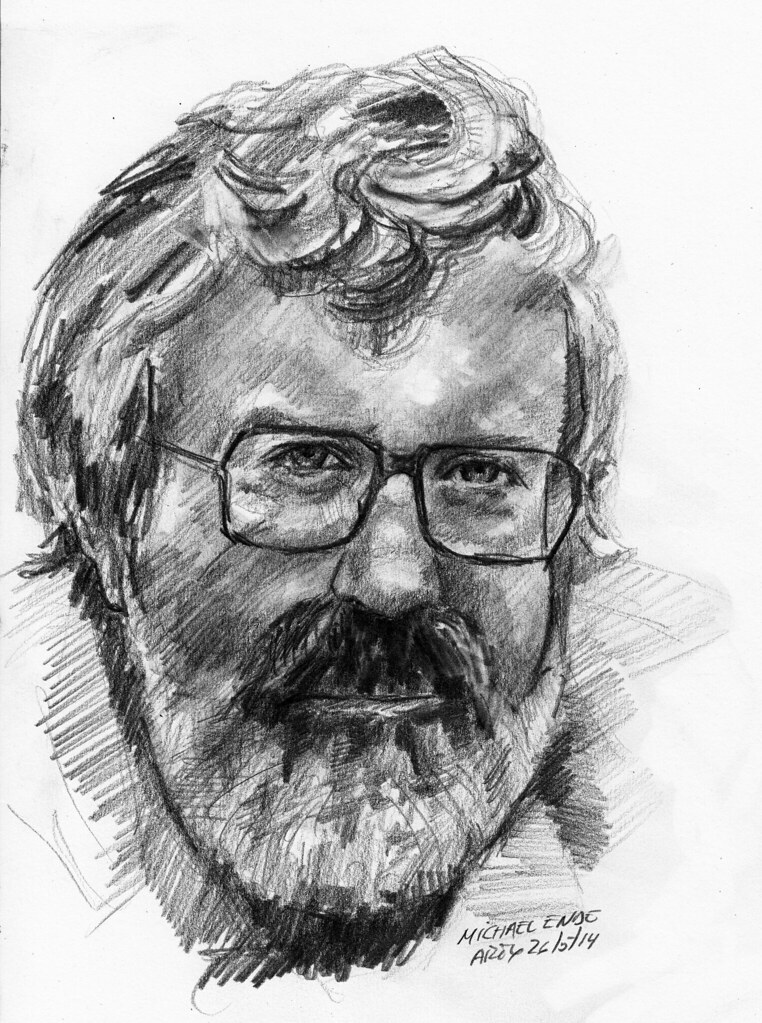

Pencil Portrait of Michael Ende by Arturo Espinosa. Retrieved from flickr.com, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (accessed: December 28, 2021).

Michael Ende

, 1929 - 1995

(Author)

Michael Ende was born in 1929 in Garmisch-Partenkirchen (Germany). He trained as an actor in Munich and worked for small theatres in the North of Germany. From 1954, Michael Ende worked as a film critic for the Bavarian Radio and also wrote humorous scenes and songs for a political cabaret. In 1956, Ende left the theatre, experienced an artistic crisis and started writing Jim Knopf und Lukas der Lokomotivführer (Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver) which was published in 1960 and was awarded the Deutscher Jugendbuchpreis (German YA Book Award).

In 1964, Ende married the actress Ingeborg Hoffman and the couple moved to Rome. Momo was published in 1972. In 1974, Momo was awarded both, the Deutscher und Europäischer Jugendbuchpreis (German and European YA book awards). 1975 it was made into an opera libretto with music by Mark Lothar.

Since 1976, Ende was involved with theatre again, with his Das Gauklermärchen (The Trickster’s Tale). In 1979, Die Unendliche Geschichte (The Neverending Story) was published. Ende was very displeased about the movie version and distanced himself from the project. In 1986, Momo was made into a movie.

In 1989, Ende, whose first wife had died, married Mariko Sato, who translated The Neverending Story into Japanese.

Ende wrote over 40 novels, fairy tales, stories, plays, essays, poems and non-fiction books and received 41 awards for his work. Over 20 million copies of his books have been published.

The International Youth Library in Munich has a permanent Michael Ende exhibition (accessed: September 28, 2018) which displays his entire works, as well as typescripts, letters, drawings, photos and illustrations from his books, his large personal library and other personal belongings:

Source:

Official website (accessed: September 28, 2018)

Bio prepared by Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Roswitha Quadflieg

, b. 1949

(Illustrator)

Roswitha Quadflieg is an author and used to be an illustrator. She was born in Zurich in 1949 and grew up in Hamburg where she studied painting, graphic design, illustration and typography. From 1973–2003 she ran her own publishing company in Schenefeld (Hamburg). Roswitha Quadflieg started writing in 1985 and since 2004 has been working exclusively as an author. She writes novels, essays, short stories, plays, audio plays and movie scripts. From 2006 to 2012 she lived in Hamburg and Freiburg where she founded the literary salon TextEtage. Since 2012 she has been living in Berlin.

Roswitha Quadflieg has illustrated adult, young adult and children’s literature, including two of Michael Ende’s works, beside Die Unendliche Geschichte: Das kleine Lumpenkasperle (1975) and Lilum Larum Willi Warum (1978).

Source:

Official website (accessed February 18, 2019)

Bio prepared by Babette Puetz, Victoria University of Wellington, babette.puetz@vuw.ac.nz

Adaptations

Die unendliche Geschichte I

Neue Constantin, Munich 1984, directed by Wolfgang Petersen, music by Klaus Doldinger.

- Die unendliche Geschichte II

Cinevox, Munich 1990, directed by George Miller. - Die unendliche Geschichte III

Cinevox, Munich 1995, directed by Peter McDonald. - DVD:

Die unendliche Geschichte I

Universum Film 2002, 1 DVD / VHS. Also as Special Edition by Universum Film/Constantin Video 2003, 2 DVDs.

Cartoon film:

- Die unendliche Geschichte II.

Das Rätsel der toten Berge. Morlas größter Wunsch. (The Riddle of the dead Mountains. Morla’s greatest Wish.) Cartoon film. USA 2001. Directed by George Miller.

Audio books:

- Die unendliche Geschichte (Audio Book)

Read by Gert Heidenreich

Hörbuch Hamburg, 2014 - Die unendliche Geschichte (Audio Book)

Read by Gert Heidenreich

Silberfisch 2013

Audio play:

- Die unendliche Geschichte

Silberfisch, 2015. - Die unendliche Geschichte - Das Original-Hörspiel zum Buch (The original audio book tot he novel)

Speaker: Michael Ende, 3 CD-Box, Universal 2007. - Die unendliche Geschichte

Audio play in 3 episodes. With Harald Leipnitz, Clemens Kleiber, Matthias von Stegmann. 3 CDs, Karussell 1980 and 1999. Also as MC.

Teaching Resources:

- Viola Herzig-Danielson, Winnetou in Phantásien (Winnetou in Fantastica)

Interaction of bibliotherapy and literary studies at the example of the Winnetou trilogy by Karl May and the novel Die Unendliche Geschichte by Michael Ende. Dobu Verlag 2004. - Andreas von Prondczynsky, Die unendliche Sehnsucht nach sich selbst: Auf den Spuren eines neuen Mythos. Versuch über eine "unendliche Geschichte" (The Neverending desire for one’s self: looking for a new myth). Dipa Verlag 1983.

Fun Book to accompany the film:

Mein Spiel- und Bastelbuch zum Film 'Die unendliche Geschichte' (My play and arts & crafts book to the movie ‘The Neverending Story’), Xenos Verlag 1984.

Translation

Die Unendliche Geschichte has been translated into: Albanian, Arabic, Basque, Bulgarian, Catalan, Check, Danish, Dutch, English, Esperanto, Estonian, Finnish, French, Greek, Hebrew, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latvian, Mandarin, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbo croat, Slovene, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Turkish, Vietnamese.

Summary

This novel tells the coming-of-age story of 11 year old Bastian Balthasar Bux, an introvert, timid, slightly overweight and un-sporty boy who is bullied at school. Bastian’s mother has died and his grieving father has lost any interest in him. When Bastian reads a mysterious book called Die Unendliche Geschichte (which he steals from a local book shop), he becomes so absorbed in the story that he is drawn into the parallel world of Phantásien (Fantastica).

Fantastica is being taken over by “nothing” and is slowly disappearing. This is connected with a mysterious illness of the Childlike Empress who rules this world. Atréju, a heroic boy of similar age to Bastian, is sent to find a cure. He is given a magical amulet for protection. After many adventures, Atréju finds out that the Childlike Empress is ill because her name has been forgotten. Bastian, who is reading the adventures of Atreju suddenly realises (just in time) that it is he who needs find a new name for the Childlike Empress. He calls her Mondenkind (Moon Child) and suddenly finds himself in front of her in Fantastica. She presents Bastian with the magical amulet which gives him the power to reimagine and recreate Fantastica.

Bastian starts using his great imagination to create a new Fantastica and also to reinvent himself to be a good-looking, brave, powerful youth. However, the more he reinvents himself, the more he forgets his own good nature and everything from his old life. As he gets overwhelmed by his power (the inscription on the amulet reads: “Do what you wish!”), he turns from a good and benevolent creator to a selfish, vain tyrant. Bastian even fights with Atréju and the luck dragon Fuchur (Falkor), who are trying help him, and finally tries to make himself the new emperor of Fantastica. Only when it is almost too late, does Bastian realise that it is not his task to rule Fantastica, but to find his way out of this fantasy world and re-enter his old life. He ceases wishing for more power, but instead wants to be loved and to love. When he meets Atréju and Falkor he hands over the amulet which gave him power and the three of them reconciliate. Bastian manages to return to his old life; and his father, who had been terribly worried for his son, now takes an interest in Bastian. The next day, Bastian returns the book Die Unendliche Geschichte to the shop where it came from.

Analysis

Die Unendliche Geschichte reads like a modern and very long fairy tale, not least because of the great number of mythological creatures (classical, non-classical and newly invented) appearing in it. It also contains an epic-style battle for the Ivory Tower. Most importantly, the plot is structured in mythological story-patterns, as typical of ancient myths. The first part of the novel, in which Atréju journeys to find a cure for the Childlike Empress, is a quest-story, like those of many ancient Greek or Roman mythological heroes. It includes him needing to pass two sphinxes. The second part of the novel is a kind of creation myth: Bastian, like a god, has the power to create environments and creatures for a new Fantastica. The dangers of this godlike power are shown through the ancient concept of hybris: Bastian’s successes and power go to his head until he almost loses his own identity. However, Bastian’s story does not end like a Greek tragedy, but Bastian realises his fatal flaw, returns his magic amulet and manages to find his way back to his old life.

A number of mythological creatures are only briefly mentioned, adding to the fantasy context of the plot: centaurs, griffin, pegasus, phoenix and unicorns. A flying dragon, the luck dragon Falkor (Fuchur), is a main character of the story, helping Atréju in his quest. Because of his gentle nature and helpfulness, including letting humans ride on his back, Falkor however, does not so much resemble ancient serpent-like, dangerous dragons, but reminds one rather of ancient stories of dolphins helping humans and letting them ride on them (such as told at Pliny, Letters 9.33). Regarding his outerappearance, association with good luck and happy disposition, Falkor is based on dragons from Chinese mythology.

Atréju in his quest has to pass two sphinxes. These sphinxes, unlike those in ancient myth, do not pose riddles, but decide whom they let pass by his worthiness. Those who are not worthy are petrified by the stare of the sphinxes, for the sphinxes’ stare send out all the riddles in the world which will petrify the victim as long as it takes him to solve them all. They let Bastian pass. The association of the sphinxes with riddles is taken from the myth of Oedipus, with the changes I have mentioned.

The werewolf Gmork is in support of the destruction of Fantastica and tries to hunt down and kill Atréju. His appearance is hardly mentioned, except his fearsomeness. Gmork does not manage to catch the boy and is finally capture and chained himself by a dark female character, called Gaya (whose name may be an allusion to the goddess Gaia). When Atréju meets Gmork, he introduces himself as “Nobody” for his protection and in order to trick the werewolf, similar to Odysseus and Polyphemus. Gmork reveals his task to kill Atréju. Atréju then reveals his true identity and that he thinks that he has failed his quest to find the rescuer of Fantastica. This makes Gmork laugh violently and he dies. Atréju approaches the dead werewolf and is bitten by him. This bite, however, saves Atréju’s life, as Gmork’s jaws clenched around the boy’s leg prevent him from falling into the approaching “nothing” until Falkor can rescue him. The idea of a werewolf as a fearful creature who hunts down humans is taken from ancient myth, however we do not hear that the werewolf’s bite will also turn the victim into a werewolf.

Die Unendliche Geschichte was also influenced by the work of Michael Ende’s father, the surrealist painter Edgar Ende (1901–1965).

Further Reading

Baumgärtner, Alfred Clemens, Phantàsien, Atlantis und die Wirklichkeit der Bilder. Notizen beim Lesen und Wiederlesen von Michael Endes „Die unendliche Geschichte“ in Michael Ende zum 50. Geburtstag, Stuttgart: Thienemann, 1979, 36–48.

Ludwig, Claudia, Was du ererbt von deinen Vätern hast... Michael Endes Phantásien – Symbolik und literarische Quellen, Frankfurt am Main u. a.: Lang,1988. (= Europäische Hochschulschriften; Deutsche Sprache und Literatur; 1071).

Schmitz-Emans, Monika, "Alte Mythen – neue Mythen. Lovecroft, Tolkien, Ende, Rowling", Chiffre (2000): 203–220.

Schueler, H. J., "Michael Endes 'Die unendliche Geschichte' and the recovery of myth through romance", Seminar 23 (2004): 355–374.