Title of the work

Country of the First Edition

Country/countries of popularity

Original Language

First Edition Date

First Edition Details

Irena Parandowska, Ze świata mitów. Warszawa: Nasza Księgarnia, 1967, 109 pp.

ISBN

Genre

Anthology of myths*

Target Audience

Children

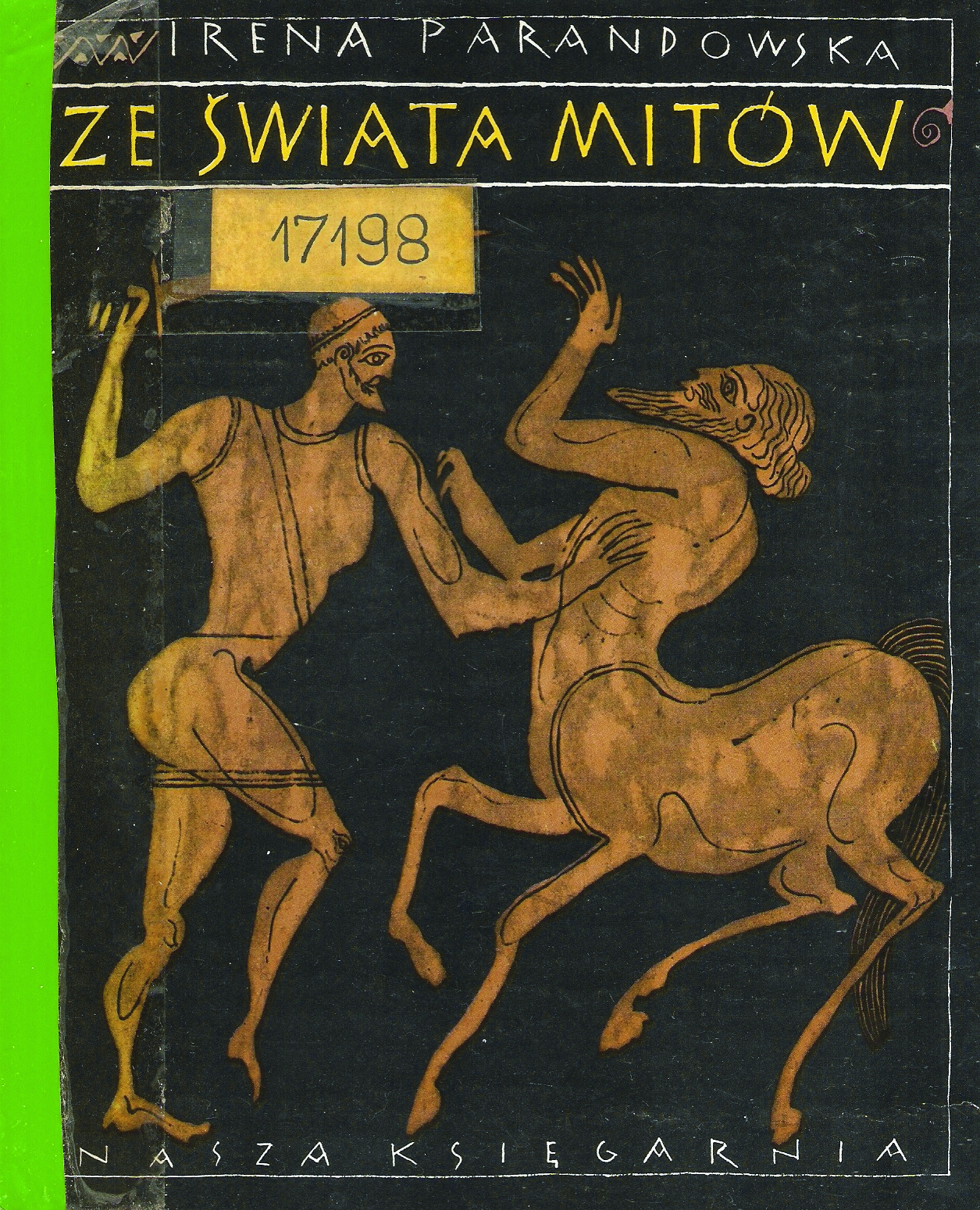

Cover

Courtesy of the publisher.

Author of the Entry:

Summary: Konrad Tymoteusz Szczęsny, University of Warsaw, k.t.szczesny@gmail.com

Analysis: Marta Pszczolińska, University of Warsaw, m.pszczolinska@al.uw.edu.pl

Peer-reviewer of the Entry:

Katarzyna Marciniak, University of Warsaw, kamar@al.uw.edu.pl

Elżbieta Olechowska, University of Warsaw, elzbieta.olechowska@gmail.com

Photograph courtesy of Ewa Parandowska, the Author’s Daughter-in-law.

Irena Parandowska

, 1903 - 1993

(Author)

Irena Parandowska (née Helcel), wife of Jan Parandowski; mother of Romana Julia Parandowska-Szczepkowska (1927–2007), Zbigniew Parandowski (1929–2017), and Piotr Parandowski (1944–2012) – a classical archaeologist and documentary film maker focusing on movies about archaeology. She wrote Ze świata mitów [From the World of Myths], 1967, and Dzień Jana [Jan’s Day], 1983 – a book about her husband. In 1988 she founded a Polish PEN Club Literature Award commemorating Jan Parandowski.

Bio prepared by Maryana Shan, vespertime@ukr.net

Józef Wilkoń

, b. 1930

(Illustrator)

Summary

Based on: Katarzyna Marciniak, Elżbieta Olechowska, Joanna Kłos, Michał Kucharski (eds.), Polish Literature for Children & Young Adults Inspired by Classical Antiquity: A Catalogue, Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, Warsaw: University of Warsaw, 2013, 444 pp.

Selection of seventeen widely known Greek myths from various sources including Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey: Pandora, Flood Myth of Deucalion and Pyrrha, Daedalus, Talos and Icarus, Persephone, Eos and Orion, Perseus, Sisyphus, Orpheus and Eurydice, Philemon and Baucis, Phineus, Pelops and king Oinomaos of Pisa, Theseus and the Minotaur, the judgement of Paris, the Trojan Horse, the story of king Midas, Arion, Jason and the Golden Fleece. These short stories are designed for children and adults who do not know ancient Greek myths. These are simple versions of myths and the Trojan epics; they hardly ever end well for the main characters. Occasionally the author changes titles of the myths: Persephone is “The Queen of Hell”; the story of Perseus is called “The Son of the Golden Rain.” Illustrations by a famous Polish artist Józef Wilkoń are based on vase painting, traditional Greek black–figure style with distinctive arrangement of figures.

Analysis

Irena Parandowska wrote an amusing collection of short stories for Polish children, in which mythical Greek characters are depicted as folk-tale protagonists. The convention of folk tales, so familiar to children, is obvious from the very beginning and at various levels – even some of the titles of the chapters like Bajka o królu Fineusie [A Tale of King Phineus] or Złoto i ośle uszy króla Midasa [King Midas’ Gold, and His Donkey Ears] suggest that the readers should expect folktales about kings, princesses, knights, dragons, treasures, heroes, and magic. In fact, the scenery of an enchanted castle and terrifying witches is used in Perseus’ myth: in a medieval castle live three guardian witches, who can ride on a shovel, and there are also enchanted people turned into stone by Medusa. Having reversed the curse, Perseus petrifies the dangerous witches. The witches have attributes of the mythical Graeae but remain unidentified; they contribute to the creepy scenery of the castle. Another example is Theseus – he defeats the Cretan monster and is rewarded by the king with his daughter’s hand. As to Jason, he marries Medea and they live happily ever after.

Each story is adapted to the target readers’ age: they are short (4–18 pages), full of descriptions, lively dialogues, and small details, such as what children like. The language is contemporary, simple, elegant and colloquial but not infantile. The characters, including the supreme gods, use everyday language as if they lived in the 20th century and not in the archaic mythical past. This narrative device makes ancient beings seem familiar to the children. For example, Persephone calls Demeter “Mum” (p. 21) and not “Mother” or “Madam” as in the 19th-century adaptations. Drastic minor plots and scary characters, potentially too harsh for the sensitive minds of young audiences, are either eliminated, presented as accidental and not intentional, or served as conventional and brutal fairy-tale justice that villains cannot avoid, for instance, in the chapter about Daedalus. The Minotaur is removed from the story (it appears in Theseus’ myth). Icarus’ fall is paralleled with Talos’ demise, as if it happened as a punishment for Daedalus’ role in the death of his nephew, even though the real cause of the death is not made clear. The Minos’ death at Cocalus’ court is eliminated – instead, Minos is chastened by the sight of Daedalus flying away again. In addition, a fairy-tale helping creature is introduced into the myth: in the seashell, lent by Minos to Cocalus’ daughters, Daedalus finds a tiny syrenka [little siren, little mermaid]. As the Polish language does not differentiate between a siren and a mermaid, the creature is a reference to the tale of the Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen, not mythical sirens. Syrenka warns Daedalus that Minos wants to kidnap him; Daedalus eventually frees her by throwing the seashell into the water during his flight over the sea. Daedalus is presented as the first mythical aviator, resulting in the association between his myth and the modern world of technology and his character becoming even closer to contemporary children.

Parandowska presents certain mythical tales less often explored in literature for children (Orion, Phineus, Arion); she reveals a broader perspective and shows rarely developed viewpoints. For example, the myth of Orpheus, usually focused on the musician and his wife, is entitled Aristaeus and Orpheus and begins with Aristaeus’ family and lonely childhood without parental care and an adequate upbringing. The death of Eurydice is presented as unfortunate and unintentional, and, in the end, Aristaeus is shown unhappy, feeling remorse and wishing for atonement. He is a future benefactor of humanity – the moral being that any blame can be redeemed. Similarly, the harpies from Phineus’ story can be considered an example of a transformation. The wind brothers, the Boreads, do not kill them; they only expel them. They explain that they fight evil and violence without spilling blood (p. 53). They spare the harpies’ lives in exchange for a solemn oath not to return. This way, even monsters are redeemed.

The author hides moral lessons in the stories, which may encourage children to reflect on the characters and their behaviour. For instance, in Persephone’s myth, she is willing to become a queen in a wreath contest ignoring her mother’s warning about the forbidden flower. Having abducted Persephone, Hades defends himself before Zeus, making Persephone responsible for the consequences of her reckless vanity: she “did not listen to her mother and picked the narcissus flower that is under my reign. She craved to become a queen. Her soul was entirely seized by willfulness and ambition. These character traits I approve. I thought – she’d be a spouse worthy of the king of Hell, she who (…) despite all the warnings let herself be seduced by the enchanting smell and did not hesitate to pick the flower whose power comes from hell.”* (p. 23) The hidden message to children is unmistakable – they should listen to their parents, who know better.

* … nie usłuchała swej matki i zerwała kwiat narcyza, który jest w moim władaniu. Pragnęła stać się królową. Samowola i ambicja całkowicie zawładnęły jej duszą. Te cechy charakteru zyskały moje uznanie. Pomyślałem – będzie godną małżonką króla piekieł ta, co uległa sile zapachu uwodzicielskiego i nie zawahała się, pomimo przestróg, zerwać kwiat, którego moc pochodzi z piekła.

Further Reading

Parandowski, Jan, Mitologia. Wierzenia i podania Greków i Rzymian, Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, 1987 (ed. pr. 1924).